For late-model stock car engine builders back in the day, it was a different time and a different place. During the 1960s and up until the late 1970s, there were no professional engine builders where a race-ready motor could be purchased.

For late-model stock car engine builders back in the day, it was a different time and a different place. During the 1960s and up until the late 1970s, there were no professional engine builders where a race-ready motor could be purchased.

Just ask Morgan Chandler, an inductee of the National Dirt Late Model (NDLM) Hall of Fame that, over the years, built about 100 engines in his garage.

Not only did Chandler (NDLM Hall of Fame Class of 2008) build engines, he used them in the late models he owned, and traveled with them as the crew chief.

Oh by the way, he also held down a fulltime job with the Rural Electric Co.

“There were times when we ran three-to-four times a week. It was a good thing that my boss was a racing fan!” Chandler said.

A vast majority of his engines competed on the short dirt tracks in the midwest around his Dry Ridge, KY home.

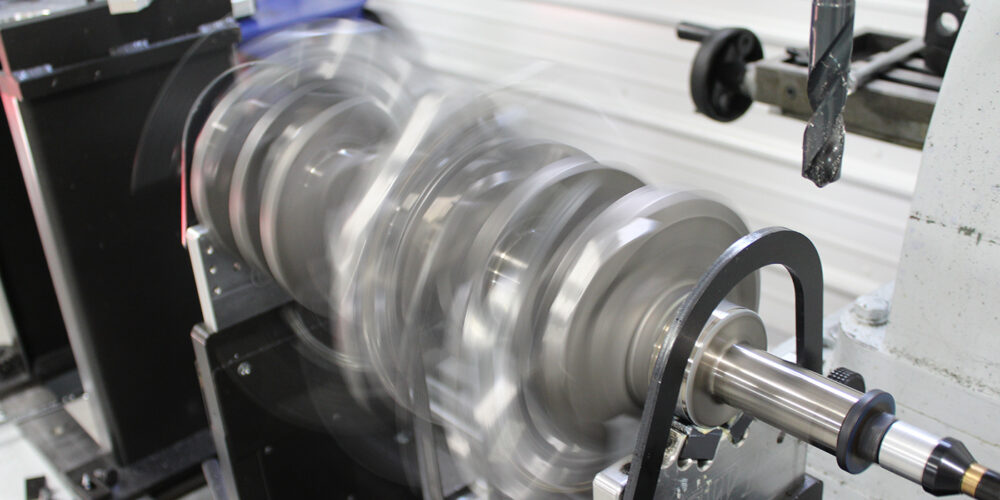

Chandler did considerable work on his engines doing valve and block work. “It was definitely a one-man show in my engine build-ups.”

He wanted his engines to live, and for that reason, he had an unwritten rule of a 7,500-rpm limit.

Even though Chandler is best known for his Chevy race engines, he actually started out with Fords. “I was using both 406 and 427 big blocks, but wasn’t having much luck with them. There were some that blew and there were problems with broken parts. And, I didn’t have the money to buy the good pieces. That’s when I decided to move to Chevy engines.”

He continued, “During those early days, I got many of my engines right out of the junkyard and built them up from there. They were dirt-cheap, and you could buy one for about $600. I really liked the small block Chevy engines.”

The skilled engine builder figured that he won about a third of his races with small block power.

“Initially, I used a 377cid Chevy, which used both cast iron and aluminum heads that I had poured myself and seemed to work pretty well.”

But when the 283 small block Chevy came onboard, Morgan jumped at it.

The design allowed him to bore them out to 302 cubes and they were very competitive. It wasn’t long before that system was replaced by the 327 Chevy which he bored and stroked to 389 cubes which was one of the biggest small blocks he built in his career.

“That was a killer race engine,” Morgan explained, “and could run with the 427 big blocks on the track. It didn’t hurt that I was running a Studebaker at the time, which was really light.”

In 1969, it was bye-bye small blocks for about a decade as he turned to the big blocks.

“To me, the best engine was the monster 454 that came along in 1970,” Chandler recalled. “I had a great deal in buying new 454 engines from a Chevy dealership. It didn’t hurt that the dealership owner was also one of my sponsors.” He indicated that he bored and stroked those engines out to 512cid.

“I remember the biggest engine I ever built was a 539 engine capable of over 700 horsepower,” he said.

In 1970, the Chandler powerplants sported one of the first dual-carburetor set-ups. It was a real kick in the pants and provided an additional 70 horsepower. Two years later Morgan started using 18-degree headers.

“It was the same stuff used by Junior Johnson. Its advantage was that it provided a wider torque range.” It was also the-first year that he incorporated a tunnel ram of his own design.

In 1974, the late model clan turned to the advantages provided by alcohol fuel. “The advantages were that it burned cooler and provided more power, but it took us awhile to getting it to work with the four-barrel carbs,” he says. It was also during this period that Morgan fielded some cars for pavement competition. “I didn’t make any changes in my engines, whether it was pavement or dirt. All the changes were made to the tires and springs. I remember a pavement race at the super-fast Winchester (IN) Speedway where I ran against Darrell Waltrip.”

Starting in the late 70’s, Morgan made a monumental change going back to the small blocks.

And, there was certainly a good reason to do it.

“Back in those days, there was no minimum weight requirement so we could use a lighter car,” Chandler said. “It also provided a better weight balance with less front end weight.”

Then, during the 1980s, Chandler investigated the effects of body aerodynamics on engine performance. This guy was always thinking ahead.

But Chandler will quickly tell you that there was certainly another aspect of his winning ways, that being an excellent cadre of drivers, which included Hall of Famers Vern LeFevers, Chuck McWilliams, Ralph Latham and Floyd Gilbert.

“Each of them had a different driving style that I adjusted to,” Chandler says. “And believe me, we won a bunch of races with them. My best season came in 1972 with Gilbert at the wheel where we won 42 races, 29 of them coming in a row.”

Chandler mentioned a few other tricks that had paid dividends for him. “I always had more ignition advance than the other teams, a richer fuel mix kept the engine running cooler, and with the big blocks I used a lower oil pressure. After all, a higher oil pressure requires more horsepower to maintain.”

His key to success? Morgan explained, “From my point of view, it was to replace many of the stock parts and replace them with stronger aftermarket pieces.” To that end, Morgan had his favorites with Weisco Pistons, Carollo Rods, Crane Cams, Wiend Intakes and Holley Carbs among others. He also had a close connection with engine builder Red Cornette.

It sure goes without saying that celebrated engine builder Morgan Chandler got much of his joy by “playing in the dirt.”