In our industry and business, one thing that has not changed is the inconvenience and total disruption to progress and profits brought along by a comeback. Unfortunately, “Failure Happens.” This might just be the next must-have bumper sticker. It could address our teenagers, our government and the occasional warranty.

In our industry and business, one thing that has not changed is the inconvenience and total disruption to progress and profits brought along by a comeback. Unfortunately, “Failure Happens.” This might just be the next must-have bumper sticker. It could address our teenagers, our government and the occasional warranty.

I won’t address my teenagers and you don’t want to get me started on the government here, so let’s address the warranty. What do we do when we have a failure? We blame the failed part of course!! Why not? It’s right here in front of us and it has obviously failed. It should be in one piece, but now it’s two. It used to have a smooth finish, but now it looks like molten metal. It used to seal combustion in, but now there are metal rings exposed and gasket material is missing. Or maybe the lobes used to all be the same, but now some are flat.

Isn’t it funny how we can read this and immediately recognize problems, but when it happens to one of our own engines the perspective changes? Immediately we eliminate any dimensional issues. Every machined surface is perfect, every torque spec met and every lifter was rotating freely in the block. Not to mention proper break-in procedures, pre-oiling and correct lubricants are beyond reproach. No sir, I’m quite convinced it was the part. After all, these things have worked for me in the past. Hence, they cannot be a problem in this case.

Before you pick up the phone to call your supplier and start pointing fingers, I’d suggest a little self examination. Check everything. Ask yourself, “If I was hired to examine this engine built by another shop and it had this failure, what would I be looking for? What could that builder have done wrong to create this problem?” Again, it’s perspective. If you are willing to except the fact that something may not have been right when it left your shop, you will be a lot less prone to overlook a potential problem and less surprised when the parts manufacturer points out something you missed that may have caused the failure.

I had a recent example of a machining mishap. A good friend and shop owner was telling me about a current project. A regular customer of his thought he’d save some money and had bought a so-called “crate engine” off the web. It had come from a shop near me and my friend thought he needed to share what goes on out there in the machine world.

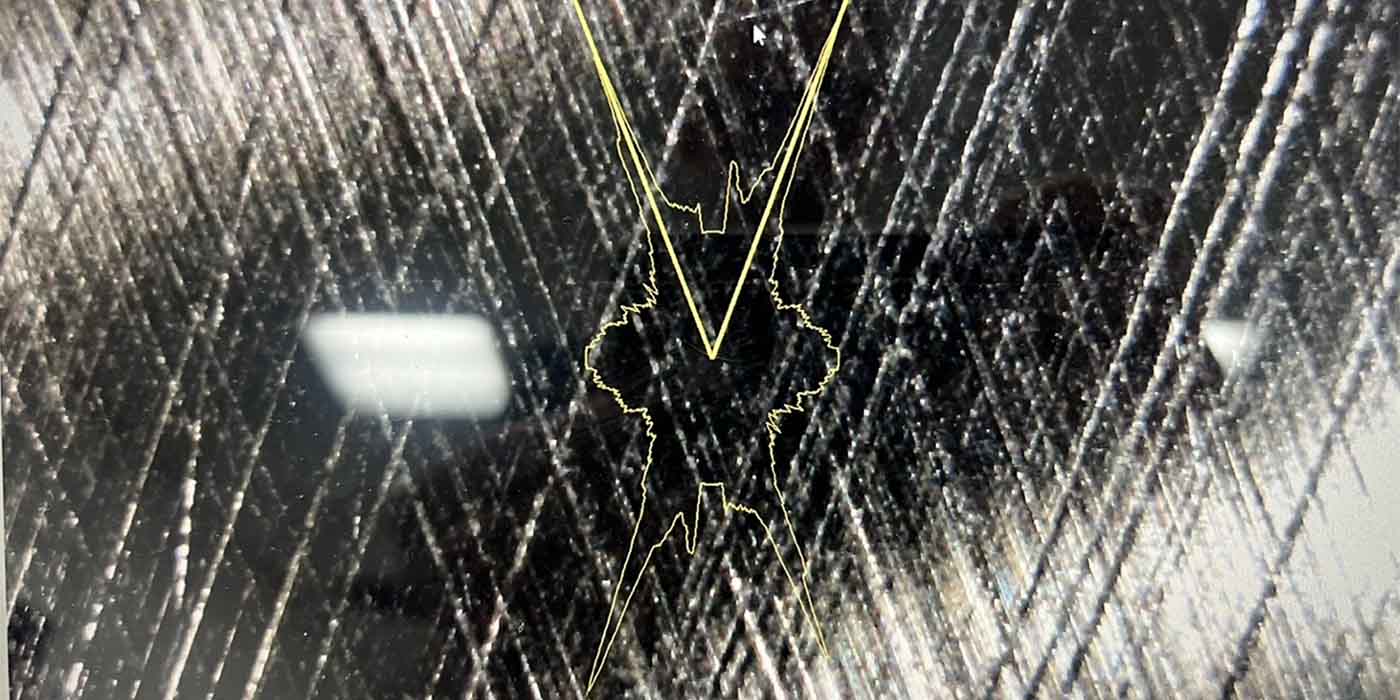

This engine had some good parts and what the consumer had felt was a fair price. For reasons unknown, he decided to bring the engine in and just have it checked out before installation in his project. First observation was less then impressive, but this was from someone who is extremely meticulous. But it wasn’t until he put the dial-bore gauge into a cylinder that the true problem was found. Somehow a cylinder bore that should have measured 4.030” was an additional .003” oversize. The cylinder bore was already worn out and the engine had not been fired.

Now. I still don’t know what shop near me this motor came from, nor do I want to know. To my friend, this was just an example of what might be going on in the rebuilding industry to give us all a bad name. What I see is just an example of how we might think everything is perfect when in fact it is not. After all, seven holes were perfect.

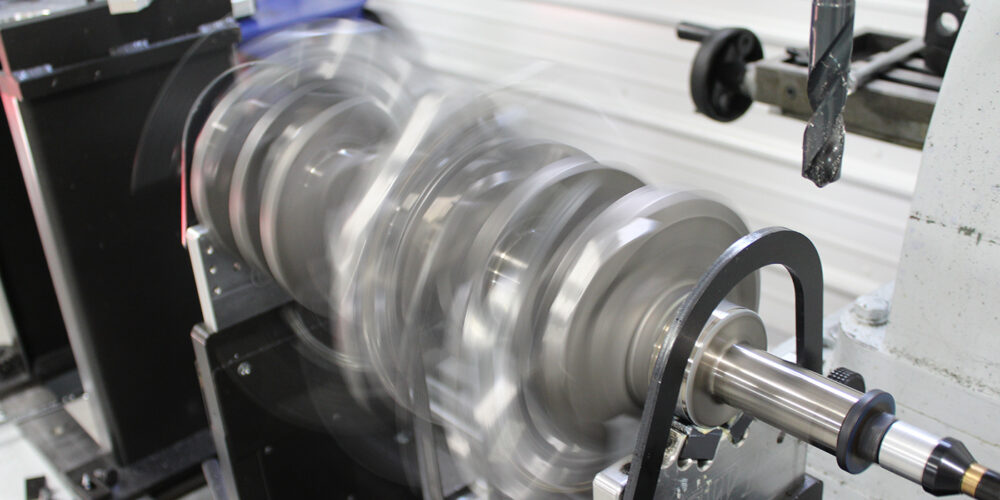

Was someone in a hurry, distracted or interrupted? I don’t know, but the fact is one in eight were not right. You could apply this observation to head, rod or main bolt torque, crank journal grinding and polishing, piston ring installation and so on and so on.

Any time you have multiple operations, the odds go up that one may not be correct. Whether it’s one in eight, or one in 34, the odds are against you if you are not 100 percent on your game when machining or assembling an engine.

Before we get to installation problems and pre-existing conditions, let’s address problem areas you may not normally have to measure or machine and may be taking for granted. After 40+ years in this business, I’ve heard a lot of stories and heard about a lot of problems. I will not say I’ve heard it all. Let’s just see what tomorrow brings.

Recently, right here in the pages of Engine Builder there was a “Shop Solution” based on technical information from Mahle-Clevite about camshaft bearings.

In that tip, I was surprised to learn that just about every engine manufactured to use cam bearings has the original semi-finished bearings bored to size in the cylinder block. After all these years of phone calls about cam bearing installation problems, I finally get the picture. Those bores and the bore alignment did not need to be perfect from the factory. But it does need to be perfect to install new finished machined cam bearings.

So if you don’t check the cam bore diameter before you install the bearings, you shouldn’t be surprised when you have troubles getting the new bearings in the hole, or when the cam won’t go into the newly installed bearing or won’t turn freely. This is a fact and you have only two choices. You can check the bore before installation, or after you’ve destroyed a new bearing.

On the subject of cam bearing alignment, I was once asked to call on a very high performance shop that was trying to build high horsepower, dependable small block Chevy engines under the then new 2-bbl carburetor rules. The rules also called for the use of stock blocks. To meet his goals this builder knew he had to look at every aspect of the engine and needed to extract as much power from each cylinder as possible. Through some meticulous measuring, he found that the cam tunnel rarely followed the main bearing tunnel exactly.

To fix this problem, he setup and align-bored cam tunnels parallel to the main bore. In some cases it took careful setup to correct the problem accurately with a .040” oversize bearing. This means the bore was off in one or more directions as much as .020”.

I could not help but apply that knowledge to camshaft failure. If your cam tunnel is going down and out at a small angle away from the front of the engine, how does this affect the cam lobe taper and lifter face radius that keeps the lifter turning? Throw in some lifter bore variance and who knows what the total stacking of these angles will produce.

In another example I had a chance to look a big block Chevy cylinder block that had seen maybe 100,000 miles of service as a stock engine before it became a high performance project that continually ate every performance camshaft the shop installed. It wasn’t until the motor was finally pulled from the car and inspected that it was discovered how far the lifter bores were out of alignment with the cam lobe. The distributor gear hit the cam gear correctly and the timing chain was aligned and straight, but when you put a light down the lifter bore you may have been as surprised as we were to see only about half of the cam lobe. It had somehow survived with stock spring pressure, but ate itself up when subjected to a performance grind and high pressure springs. Needless to say, this all started with a claim of a “soft” camshaft.

Today, it doesn’t just seem engines are lasting longer, they are lasting longer. At one time we were impressed if an engine went 100,000 miles without major repair. We could also bank on the fact that once they reached the six-digit mileage they were ready for a rebuild. Somewhere along the way, someone threw a wrench into the works. A second industrial revolution was upon us. The electronic revolution infiltrated our grocery getters. After a brief period to sort things out, modern electronics have made a huge impact on the life of the internal combustion engine and consequentially on our businesses.

Like most things, when everything is in good order, great results happen. If your computer, ignition system, fuel pump, injectors and all the electronic sensors and components are working properly, long service, good fuel mileage and good performance happen. But what happens when any part of the system goes bad?

At this point there is a good chance the engine will end up in your shop. To start, you teardown the engine, find the source of the oil consumption, the cause of the noises coming from inside or the failure. We estimate, machine, acquire the needed parts and assemble an engine that is as good as or better than the day it left the factory. Yet, we can still have a comeback. “How in the world can this happen to me? What happened?”

I’d say we are asking questions at the wrong time. I ask,” Why did the engine come in to the shop in the first place? What failed and why?” Given that many engines make it 250,000 to 300,000 miles, why didn’t this one? Then I’d ask, “Did that cause a failure the second time?” If the engine had a bad injector and was running lean in one hole, was this addressed before these parts were bolted on to the new engine?

Several years ago, the Windsor style Fords suffered from a crossfire condition that would cause detonation and destroy pistons. More than once I heard about failures that were traced back to unrepaired or replaced ignition wires that caused the remanufactured engine to fail just like the first.

The new modular Ford V8s have been known to have catastrophic failures that send debris back up into the intake manifold and plenum. It’s no mystery that this debris will make its way back into the new engine if the manifold and plenum are not cleaned properly. Detonation was a problem for the early version of these motors. The engine controls that were at fault and caused the failure will become equal opportunity destroyers for engine number two, as will any debris.

I was recently contacted about such a failure. To make matters worse, this engine is supercharged. There were problems with the first engine. The car was sold off cheap as a project for some unsuspecting buyer. Within 60 miles the new engine grenaded a piston. There is not enough of this hypereutectic piston left to really examine to determine what happened. All eyes and blame are on the piston. A lack of understanding that though they may be tougher than a traditional cast piston, a “hyper” piston is still a cast piston, and if you hit it with a hammer, it will shatter like glass.

I do know that there are seven other pistons that look good, and since they were all made at the same time, all from the same batch, it is not fair to simply blame the piston. I fear that the original problem that caused a failure was never addressed. Add a little boost and you have catastrophe.

Now there is nothing the parts manufacturer and the parts distributor has any control over here. Granted, you could say the same for the engine builder who did not do the install. I do not know if he even installed the manifold. But now the car owner is upset, ignorant to the fact that it took something more than an act of God to destroy the piston.

In the mess that ensued, who could identify any additional foreign matter amongst the piston fragments to blame for contacting and destroying the new slug. More likely it is something in the controls for the fuel or ignition system that caused this. If I understand correctly, the install and initial firing of the new engine was done by the car owner and a buddy – not a professional. I can only hope a “Pro” would have thought to look into what caused the first failure, but I am not very confident this would’ve been the case.

There is also the stark comparison between the failure rates for some P.E.R.’s verses custom builders. The custom builder gets a chance to look at the original engine and hopefully ask and detect what caused the failure.

Not so the P.E.R. He may not see the core motor for a week or more after he delivers his remanufactured product. It generally goes to a teardown room and no one thinks twice about the condition of this “core.” This is a mistake in my mind. If a close inspection was performed and any cause and effect noted, this could be used to protect you from any future failure claim. So when given the chance up front, there is really no excuse for the custom builder to not ask and note problems right from the start. If anything is found that may have caused the original motor to fail, it might be noted on your work order. It should be stipulated that the engine carries no warranty if this condition is not fixed before the new engine is fired.

At this point, we’ve made sure all of our machining processes and our assembly was flawless. All the ignition and fuel system components check out well. We’ve also verified that the original engine failure was completely different and unrelated to the warranty condition. So now we have no place to turn but to look at a possible part failure. If this is the case, handle it correctly.

Get the required warranty claim form from the part manufacturer. Fill it out completely. Supply all the required receipts pertaining to the original engine job and installation, and all the receipts for the current repair. Create the perfect paper trail. Show that everything was done correctly and outline exactly why it could only have been a part failure. Submit everything for inspection and be patient. Usually these things take time.

One last suggestion, do not put together a request for the most amount of reimbursement, with the thoughts that you’ll be happy with what you get. I have been far more successful with claims that were fair or even a little less than fair.

Put together a parts list; do not add tax or any other shop fees. For labor, use book time and a $35-40.00 per hour charge. Enough to cover you or your employee’s time. This is not something that will be profitable. There is a cost to doing business, and in this case it might be a small loss of your time. This too must be explained to the installer. The best that can happen for all is to try to make it right for the consumer.

Get the job done and get their vehicle back on the road. The reimbursement, whatever it will be, may or may not come in time. Sometimes things are out of our control.

Sometimes, “Failure happens.”