If one of the most recognizable hosts of one of the most popular automotive-based reality TV shows came calling and asked you to build a blown big block to squeeze into a vintage collector car to help celebrate the history of an iconic toy, would you blink?

For Jammie Wells, it’s just another day in the shop.

Richard Rawlings, owner of the Gas Monkey Garage in Dallas and host of “Fast N’ Loud,” a reality television series on the Discovery Channel, was given the opportunity to build a replica 1968 Corvette to celebrate the Hot Wheels Sweet 16, the first series of toy cars produced by Mattel in 1968. He immediately had visions of a blown big block engine to power the classic, and he called on WCH Racing Engines in Midlothian, TX to build it.

It wasn’t Wells’ first experience with building for the television series, and this engine, based on the ’68 Corvette’s original 427 big block, developed into a real beast. Chromed, blown and downright nasty, the engine in the gold Midas Monkey pumps nearly 700 horses through a Weiand Supercharger, twin Holley four-barrel carburetors and custom headers. Wells says the engine could be even more powerful than it is – but this is a reminder that “reality” doesn’t necessarily mean “real.”

Wells says he’s worked with the Gas Monkey gang for four years, although it hasn’t always been a smooth road. “I’d been bugging them to get involved with the show but couldn’t get anywhere with Richard or Aaron Kaufman (the Gas Monkey mechanical genius) until another one of my circle track customers told them about me. One of the first engines we did was the motor in Burt Reynolds’ Trans Am.”

Without throwing anyone under the bus, Wells suggests that the TA and another engine WCH and Gas Monkey did together in the early days were, well, challenges. “We didn’t have our dyno yet, so the engines weren’t broken in the way we would have. I’m really thankful to Richard and Aaron, because they could have easily said, ‘We don’t want to have anything to do with you guys – you guys suck,’ when the reality is different. Since then we’ve done about 15 builds with them.”

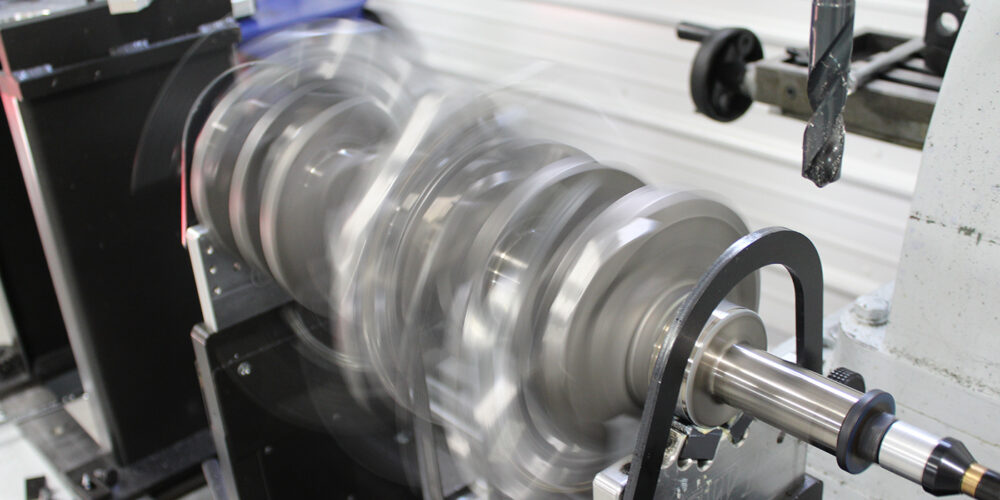

To meet the rigorous standards of a TV production (and to ensure that producers can’t manufacture any extra drama) WCH dyno tests every engine it sends out the door on its Stuska TrackMaster engine dyno. “Oh man, I put it through vigorous tests,” Wells says. “I let it sit there and just let it run with a load on it, like you’re going down the highway. Just making sure that when they put it in, there is not a problem. We even change the oil before it goes to them, and put more break-in oil in it. I mean, I make sure I double, triple check everything before they get it now. And since we’ve been doing that, we don’t have any troubles at all. And it has really, really been great.”

In addition to “Fast N’ Loud,” WCH Racing Engines is the go-to engine shop for other Dallas TV series including “Misfit Garage” and “Dallas Car Sharks” and Wells is quick to point out that, despite the allure of dealing with celebrity TV hosts, hanging out in VIP areas at vehicle unveilings and being recognized when he walks into a grocery store, he has to keep his game sharp.

“Here’s where I lose out on these shows,” explains Wells. “It’s when someone like GM gives them a crate motor – they can just call up a dealer and get a motor and transmission complete…for a smoking deal. But here’s where I win: they can’t call that dealer and order up an old Cadillac 500 motor, or an old 430 Buick motor, or a big block blower motor for a ’Vette. They can’t. They’re going to get that from, where else, me.”

As exciting as the TV lifestyle is, Wells says his main business continues to be building engines for the circle track racing community.

“That is our bread and butter. I mean literally, we build at least one dirt track engine every day. There’s no if, ands, or buts about that. In addition, I’m really concentrating right now on Show Car events. I’m trying to increase my exposure for classic engine builds. Engine builds like this ’Vette, street rods and stuff like that. And of course, the LS industry is here.

“The LS engine foundation is just an unbelievable engine base – it’s just phenomenal. They’re cheap horsepower to build for an old classic car, hot rod, even drag racing now. Most of any turbo work we do is with the LS platform. It’s just becoming the thing.”

If Wells sounds like he feels the LS is a double-edged sword, it’s because “cheap” isn’t necessarily a good thing for his marketing plan, so he’s not competing against them. But unlike his concern for crate engines impacting his TV business, he says the racing scene isn’t so fragile.

“Here in Texas, it isn’t like it is up north,” Wells says. “You don’t see nearly as many crate motors here. Here, you may see two out in a field of 28 cars. Up north, I think it’s closer to 50/50. One of the biggest dirt track fads around here right now, is a class called the Factory Stocks. There are no crate motors involved. And that class is just unbelievable. We are building more factory stock engines right now than we do anything else.”

Wells says these race motors are built with inexpensive parts: no forged pistons, no aftermarket rods, no aftermarket cranks. Old school, cast iron or aluminum GM intakes.

“They’re called ‘factory stock’ engines for a reason,” Wells says. “They have a cam lift rule of .450˝. There are guys who may spend $30,000, $40,000, $50,000 on a modified engine who are leaving their modified IMCA programs to go to factory stock. Why? I’m really unclear, with the exception of the fact that there’s a lot of high dollar shows put on just for the factory stocks: $2,000, $3,000, $4,000, even $10,000 shows. You just don’t see that for modifieds anymore. I enjoy it: no crates involved. Not just me, but all engine builders are busy because of it.”

Wells believes that one of his keys to success is the fact that he has a large shop with plenty of equipment, yet he has kept his overhead down.

“I have no overhead,” he says. “Everything’s paid for. I broke myself paying for it, but now I’m relaxed.”

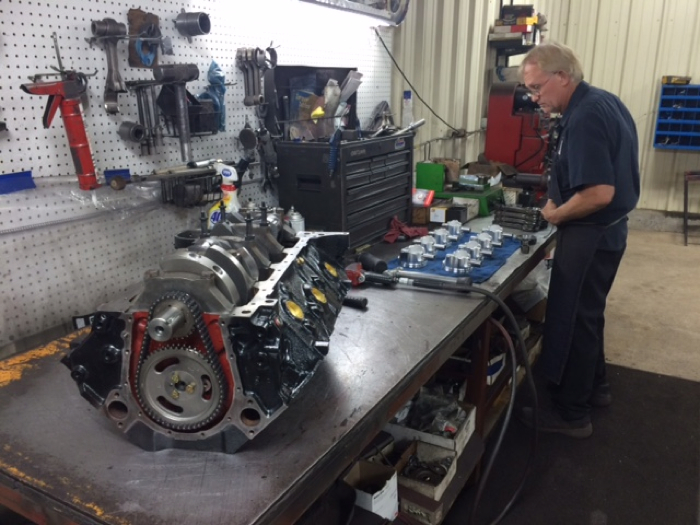

Wells employs four employees in his Midlothian shop including himself: Mike Morphew, engine assembly; Manuel Serda, cylinder heads; and Mark Allen Earl, teardown; and relies on a partnership with EPWI for most of his parts and Ferris Equipment for much of his equipment.

WCH Racing Engines’ machining department includes a Rottler boring bar, Peterson surfacing machine, Bridgeport Mill, Sunnen line hone, cylinder hone and rod hone; Hines balanancer and Stuska dyno. Because he also does significant production cylinder head work, a CNC might be on the horizon, despite Wells’ reluctance to take on overhead.

“Yes, I would love to have a CNC machine. But years ago I thought a dyno was out of my reach, and now I have one. With production cylinder head rebuilding it might make sense,” he says.

In addition to the race and hot rod motors, WCH Racing Engines is active with 5.9L Cummins – though Wells admits the customers are harder to categorize.

“It’s kind of crazy – diesels are different than gas engines. I do more just machine work for diesels, like grinding the crank, prepping the block and selling an engine kit. My diesel customers seem to want to put their own stuff together.”

Wells is also involved in building gasoline engines for toy mud trucks. “These big monster trucks are generally like a big block 454, something with high torque mode. 2015 was the first year I really got my foot in the door with these guys – we’re talking trucks are hauled with 18 wheelers, not streetable stuff.”

With customers driving everything from a ’50 Cadillac to the guy with a turbo diesel truck to a circle track race engine, Wells depends on social networks to get his name out. That means word of mouth as well and electronic media.

“When I first started I spent lots of money in the yellow pages; but really, social media is huge with engines. When’s the last time somebody picked up a phone book? I’ve got a lot on Facebook. You could look up our shop address, our phone number. On our like page I even throw out pricing on new packages and stuff for circle track packages,” Wells says.

Wells cautions that relying on social media can be great as long as you watch out for backlash. “You also have the chance of having things go wrong on Facebook, so you really have to watch what people are saying about you. There’s no doubt about that. Social media is absolutely crazy. Holy cow, you’ve got to be careful with it. Especially when you get popular – you really find haters, there’s no doubt about that.”

Growing up in the automotive industry (his father owned salvage yards in Grand Prairie, TX), Wells had an early attraction to the mechanical industries. “I worked in a brake and alignment shop, and next door to us was the guy who ran a shop called Texas Cylinder Heads. Wayne Wallace – his nickname was Moose – was the owner, and at lunch every day, and in the afternoons, I would go over and watch him put heads together, do port work, screw in studs and guide plates. He did a lot of local circle track cylinder heads,” he recalls.

“So somewhere around 20 years ago, after working for a small engine shop in Cedar Hill, TX and then a large cylinder head production shop, I bought a valve grinder and a jet washer and started by myself in a little barn,” Wells says. “And because it wasn’t really a presentable place, I picked up and delivered everything.”

Wells says he’d go to salvage yards and say “’You ought to rebuild these different heads and put them on your shelf.’ If it was high failure cylinder head at the time, we’d bring it back, prepare it, fix it, and I’d deliver for them. But those salvage yards, if they didn’t have a head the customer needed, would just send them over here. There were some embarrassing times because the shop was horrible! I didn’t want anybody there! I was fortunate enough to be able to buy this property and build the first part of the building.”

Success begets success, and Wells began to add on to his business; first came a core storage building, then an expanded teardown and cleaning area, then a custom dyno room, and finally an expanded assembly area. Next up? Wells has his sights set on a chassis dyno.

The Midas Monkey

Wells says that working with customers such as Gas Monkey sometimes means he doesn’t have much input in parts selection. Certain companies may have advertising agreements with the shops and their parts need prominent placement in a build. In some cases, boxes of parts will show up at his shop and he’ll need to figure out how to make them work. Luckily, if they’re not right for the application, he makes his own parts selection.

In the case of the 1968 Corvette, Wells says the supercharger and carburetors sat on top of an Alkydigger spacer. Inside, the motor has Comp cams and lifters; CP-Carrillo Bullet pistons, a Scat crankshaft and forged I-beam connecting rods; Manley valves; King engine bearings; Melling oil pump; Kevco oil pan; Engine Pro billet timing set and ARP bolts.

“With this one we used bolts,” Wells says. “They didn’t want us to use the studs because studs will sometimes bump into the headers, and since Aaron was custom-fabricating the headers from scratch, he already had enough troubles and didn’t want to have to deal with studs.”

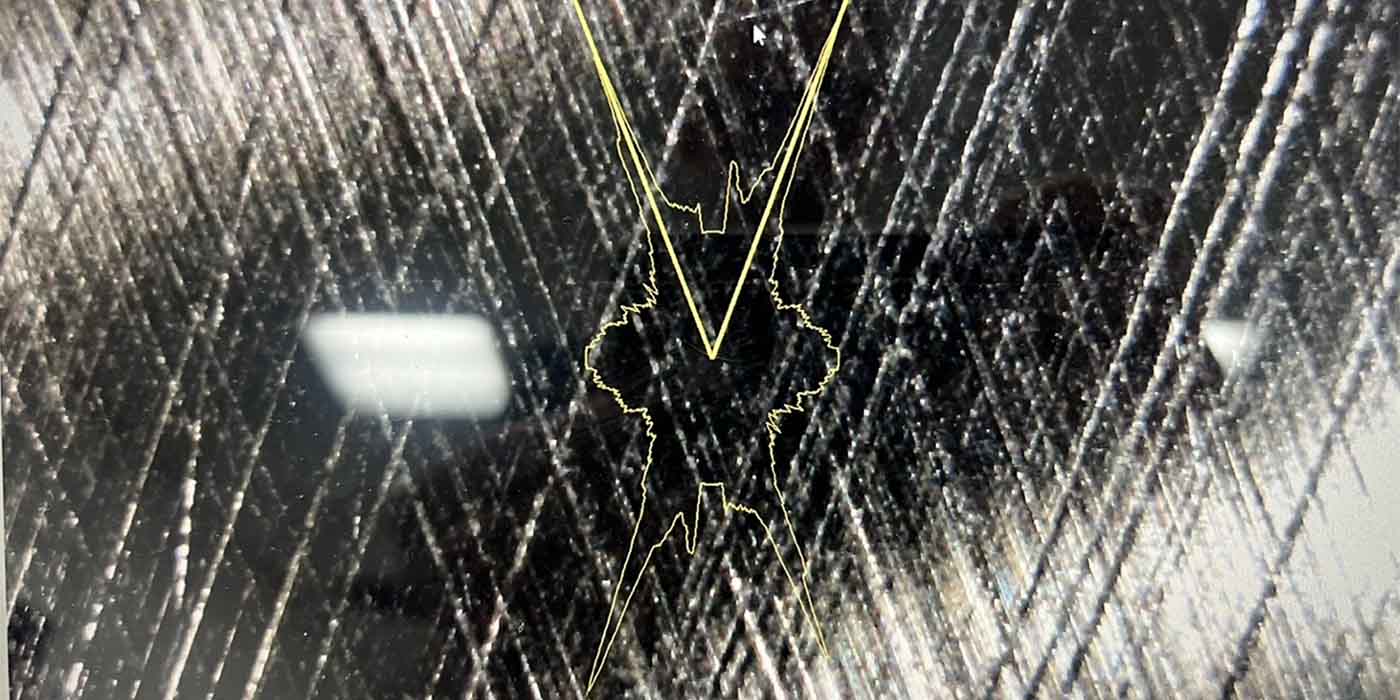

The configuration of this engine required Wells to run three different break-in procedures on the dyno. “We couldn’t order a blower belt until we knew exactly how tall the spacer was going to be,” he says. “We ran it first with just the carburetors, then we ran it with the blower and finally with the spacer in place. Final output was just shy of 700 horespower.”

So What’s Next?

Although he admits he didn’t get into this business to be a TV star, Jammie Wells says he plans to continue looking for opportunities to partner with celebrities. “Again, on the business side of it, this is not what I headed out to do. But now I’m all into it and I want to nail all of these other shows including ‘Street Outlaws.’ We’re talking 700-800 cubic inch motors.”

And that celebrity is a great business tool for the rest of his business and allows him to be an advocate for the industry.

“You know, I get calls from our local high school – people there are interested in the industry. Matter of fact, I’ve even gotten some emails just asking me about the industry. And I think that the only reason they ever called us is because they saw us on TV. ‘Hey, what’s it like in your industry? What’s it like owning a shop? Is there any money to be made?” Wells says.

While it looks glamorous on TV, Wells says he wants to be sure the next generation understands the opportunities that exist.

“I wonder who’s going to be putting engines together in my shop in 15 years? Because I have no intentions on shutting my doors any time soon. I’ll probably do this until the day I pass. And I need the younger generation that wants to help do it!”