In this industry, it’s often cheaper to remanufacture or rebuild an engine than it is to make a new one. However, doing so requires cleaning worn and dirty parts. In addition, customers these days are increasingly asking for cleaner parts and engines. How are you supposed to get tough grease, oil, rust, paint, carbon build-up, dirt and many other kinds of contamination off? One way is the use of blast media and blast machines.

Blasting is a popular process in reman facilities and engine shops to clean those worn and dirty engine parts via media such as steel shot, ceramic shot, plastic, baking soda, aluminum oxides, glass bead, steel grit, crushed glass, and more. The machines and cabinets used in conjunction with those media also come in a variety of sizes, manual or automated, dry blast or wet blast, and so on.

With so many options available, how do you choose what media and machines could work for your engine shop? Well, it depends on what you’re looking to clean and how much you have to clean. Different media and machines have to be considered if you are cleaning larger parts versus smaller parts, more parts versus just a few, different part surfaces, and whether or not you can afford to have surface wear on a part.

If you’re just starting to investigate the benefits of blasting or are still getting your feet wet, it may take a little trial and error to find a suitable process for your application.

“We research processes and products to find out what the value of each abrasive, machine and process holds,” says Thom Bell, vice president of Precision Finishing Inc. “We use that information and design experiments, which become baseline results to improve upon. We’re constantly learning as we go.”

Blast Media

There are two general media families when it comes to abrasives for engine parts – round media and angular media. Round media is less aggressive and used on softer metals, where angular media cuts and is more aggressive, even wearing down the surface of parts at times.

“Angular media is exceptional for cleaning tough material like rust,” Bell says. “Because it’s sharp you’re going to be cutting the contaminants off, but at the same time, you’ll be affecting the substrate. You’re going to alter surface finish or some dimension.”

Angular media are typically aluminum oxide, steel grit, crushed glass, or garnet. Round media such as glass bead, steel shot and ceramic shot are for cleaning surfaces that have a low tolerance level.

You will also be imparting compressive stress with a rounded product. You’re essentially peening the surface while you’re cleaning it.

“In some cases that’s a good thing and in some cases that’s a bad thing,” Bell says. “If you use a rounded material on a thin-walled sheet metal you’re going to peen that surface and it could bend and warp. But if you use a rounded material on a connecting rod or a spring, you’ll be cleaning the surface and you’ll be introducing compressive properties, possibly strengthening it based on blast pressure.”

There are two different types of dry blasting – using air to propel the media or airless/throwing the abrasive with a wheel. Airless is typically higher energy than air blast, and certain media can even get stuck in part surfaces. In areas where you must be delicate and you don’t want to have a lot of impingement and material removal, air blast might be more desirable.

For these instances, glass bead, plastic media and baking soda are typically used. For airless blasting, commonly steel shot and grit are used. The key to understanding what media might be best depends on the part you are trying to clean and the results you are trying to achieve.

“If you’re cleaning a starter housing, or a water pump, or those types of aluminum castings, you can use a steel shot,” Bell says. “But if you’re talking about the guts of the engine, or the guts of an internal part, you don’t want to change that surface. You don’t want to mar the surface or change dimension of the surface. You’ll want something less harsh such as glass bead, ceramic bead or baking soda.”

On cast iron engine blocks and heads, some remanufactureres use steel shot, incorporating that process with a bake and blast system to get all the oil and gunk baked into a powder.

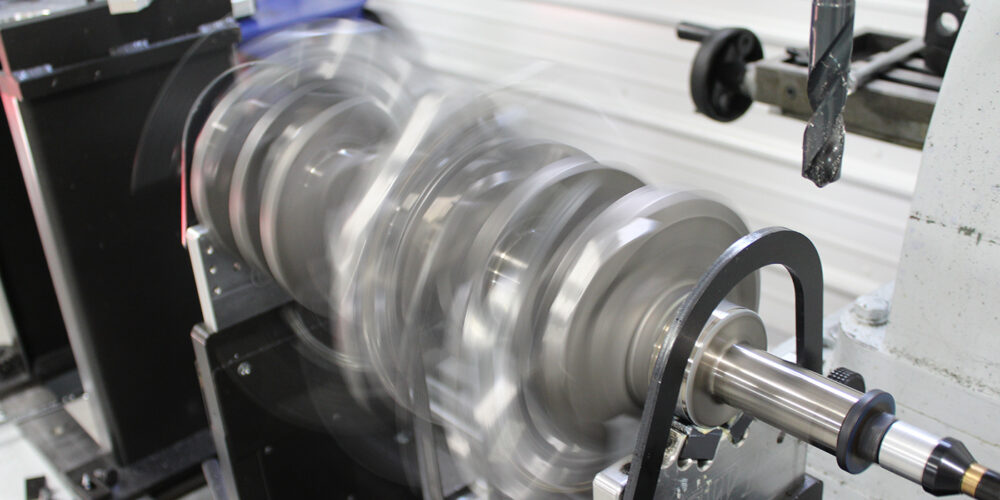

“Then we put the block into a rotary-type blasting cabinet that’s throwing steel shot at it and the casting comes out looking new,” says Randy Bauer, Gas Engine Division manager, Jasper Engines & Transmissions. “We do have to put them through a process after that, which is tumbling to make sure all the steel shot that was thrown at the block comes out of all the different holes, crevices and cracks.”

When it comes to aluminum, Jasper turns to either plastic media or baking soda. Plastic is a little bit more abrasive than baking soda, and Jasper uses plastic in a manual blasting cabinet.

“Of course, the aluminum part would have already gone through some other cleaning processes such as a spray cabinet to knock all the residual oil and wet stuff off of it so it’s just dry gunk and carbon that’s left over,” Bauer says.

For cleaning aluminum and small parts that have critical areas where plastic could get embedded or lodged, which would be detrimental to a part, soda blasting is the best option.

“The beauty about baking soda, although it is a one use product, is that it won’t get caught in the surface of a part,” Bauer says. “You can rinse the soda to dissolve it away. The downfall to soda is it’s not quite as abrasive or aggressive, so it will take longer to clean a part.”

Baking Soda

The one thing to understand about baking soda is that it is not a single, fix-all type product. It really comes down to what you’re trying to clean and what the expectations are for the end user and customer.

“The reman industry really lends itself very well to baking soda versus other medias,” says Brian Waple, business manager, Church & Dwight Co., Inc., makers of ARMEX. “The big thing we positioned ARMEX in was called nondestructive cleaning surface preservation, meaning that when you’re using harder abrasives, whether it be crushed glass, glass bead or garnet, those will remove surface materials from the substrate, which might not be a wrong thing, but it really depends on what the prerequisite is.”

If you’re blasting a turbocharger or an aluminum head, once you use a hard abrasive, it will remove surface material and change the specification and tolerance on the part. Baking soda won’t do that. It just removes the contamination.

When a baking soda crystal hits the surface area, the impact of the crystal on the surface causes the crystal to explode. When it explodes, that’s when it’s removing the contamination off the surface area. When hard grit hits the surface area, it doesn’t explode on the surface, it digs into the surface and removes surface material with the contaminant. That’s the big difference between the two.

“What a lot of people are starting to experience in the reman industry and engine building industry is that the harder abrasives are stripping threads,” Waple says. “They needed to get away from that because once you strip a thread, you’re adding another step to the process to rethread it.”

Another advantage to baking soda is that it loves grease and oil. A lot of times when you’re using harder abrasives, yes, it’s removing contaminants, but it can leave a film on the surface area where baking soda completely removes all that grease and oil. Baking soda can also be used on a part that hasn’t gone through a pre-wash process, but should be rinsed after blasting.

The other big advantage of baking soda is it is soluble, meaning with a fresh water rinse, it dissolves. “Any small particles left in passageways or hidden areas that you couldn’t get to will dissolve,” Waple says. “If you leave a glass bead behind and you fire an engine up, you could have an engine failure. Baking soda particles that are left behind won’t damage your part or your engine.”

Baking soda is also environmentally friendly. When you’re done blasting, the baking soda isn’t considered hazardous material.

“Because baking soda is a one pass product and can’t be re-circulated and used again like other media, usually, the ratio of baking soda compared to contaminants puts it at a level where it doesn’t need special handling and disposing,” Waple says.

Baking soda will remove baked-on carbon, grease, oils, paints, epoxies, and even old gasket materials. ARMEX can take off up to a 20-millimeter dry film thickness of a two-part epoxy paint. Anything more than that, you’ll need something more aggressive. Baking soda can be used on starters, alternators, starter pulleys, aluminum heads or blocks, pistons, crankshafts, turbochargers, valves, camshafts, brake calipers and more. “Anything aluminum is a no-brainer to use with ARMEX,” he says.

There are some downsides to baking soda, however. One of the biggest challenges is that baking soda requires the use of specific, unique equipment. If you have a sand blaster or a glass bead blaster, you cannot simply use baking soda in that equipment. You have to get a whole other cabinet.

In addition to needing its own specific equipment, baking soda is lesser known in the industry compared to other media. There is a slight education process to get potential customers to understand its many benefits.

“If nondestructive cleaning is important to you, ARMEX and baking soda is the way to go,” Waple says. “When you think about the efficiencies in how fast it cleans, the quality control and maintaining the part, and also alleviating the pre-rinse and repairing damaged threads – it’s cost justified to use soda.”

Dry Blast Machines

One of the biggest challenges with baking soda is dust control. When you’re in a cabinet versus using other medias, soda makes a lot of dust. And when you have a lot of dust, it can sometimes be difficult to see the part.

“Clemco recently launched a new high-capacity cabinet, which clears all the dust,” Waple says. “And there’s a lot of equipment on the market, and a lot of different price points.”

Again, with so many options available, what’s the best cabinet to use? You have to really evaluate your process. If you’re in a small engine shop and you’re blasting parts here and there a couple hours a week, you’ll want to consider price point. If you’ve got operators that are blasting parts two shifts a day, five days a week, then you’re going to a more substantial unit.

“Media and blasting equipment go hand-in-hand together,” Waple says. “You obviously can’t use one without the other. So equipment is super important.”

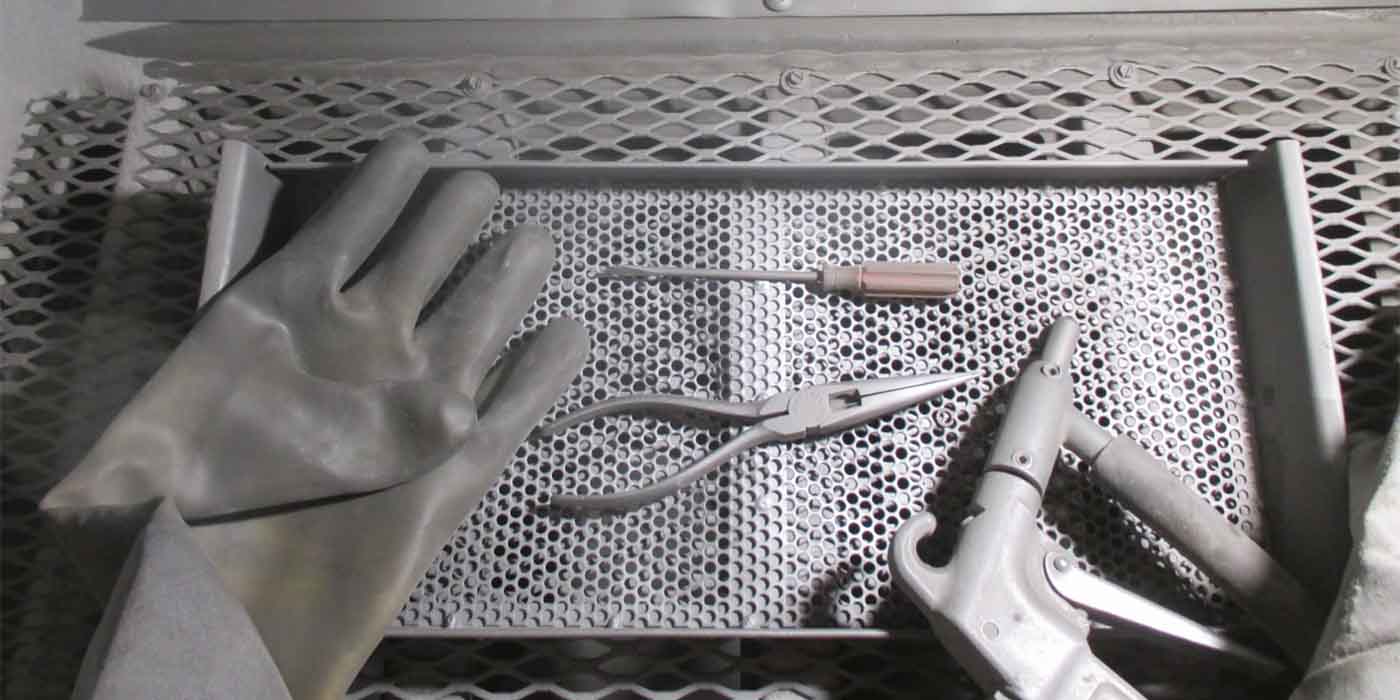

At Jasper, blasters for baking soda and plastic are manual cabinets where you put the part in, close the door, stick your hand into a long pair of gloves and hold a nozzle and blast the part. Jasper’s block blasters are more automated. You put the block or the head into the machine, close it up, push a button, and it rotates the part and throws shot at it.

“We have an array of different machines here,” Bauer says. “We’ve not settled on one type. We’ve been happy with what we currently have because it serves the purpose.”

Bauer says the key for machines, no matter what type of media you use, is getting the part in a standard condition before it goes into the machine you’re using.

“The cleaner that you can get a part before you have to put it in a blaster, whether that be through baking or aqueous cleaners, the easier it’s going to be to blast that part,” he says. “If you put a dirty part in and it’s got some wet oil on it or it hasn’t been through an aqueous cleaner, it’s going to take you a lot longer. You then have the extra labor and expense of the media that it’s going to take to clean that part up.

“Aqueous cleaning tanks have their limitations on what they’re going to be able to clean and how long you can leave a part in there. A lot of them aren’t going to take off silicone. They’re not going to take off all the carbon, and that’s where the blasting comes into play.”

A key thing not to overlook as far as dry blasting equipment is concerned, is making sure that you have a very good reclaiming system to pull out all the dust that’s being created by the cleaning and the media.

“There’s equipment out there that won’t do that and there’s equipment that will do that,” Bell says. “There’s a couple of production blasting machines out there that clean themselves. Basically what will happen as you’re blasting is the machine will remove the spent or broken abrasive and it’ll eventually run out of abrasive. All you’re doing is adding abrasive. You never take it away, because the machine is taking it away for you.

“A lot of times people will take the abrasive out of the machine, throw it away, and start all over again. And that’s wasteful. It costs money and it’s more labor. A good machine will clean itself.”

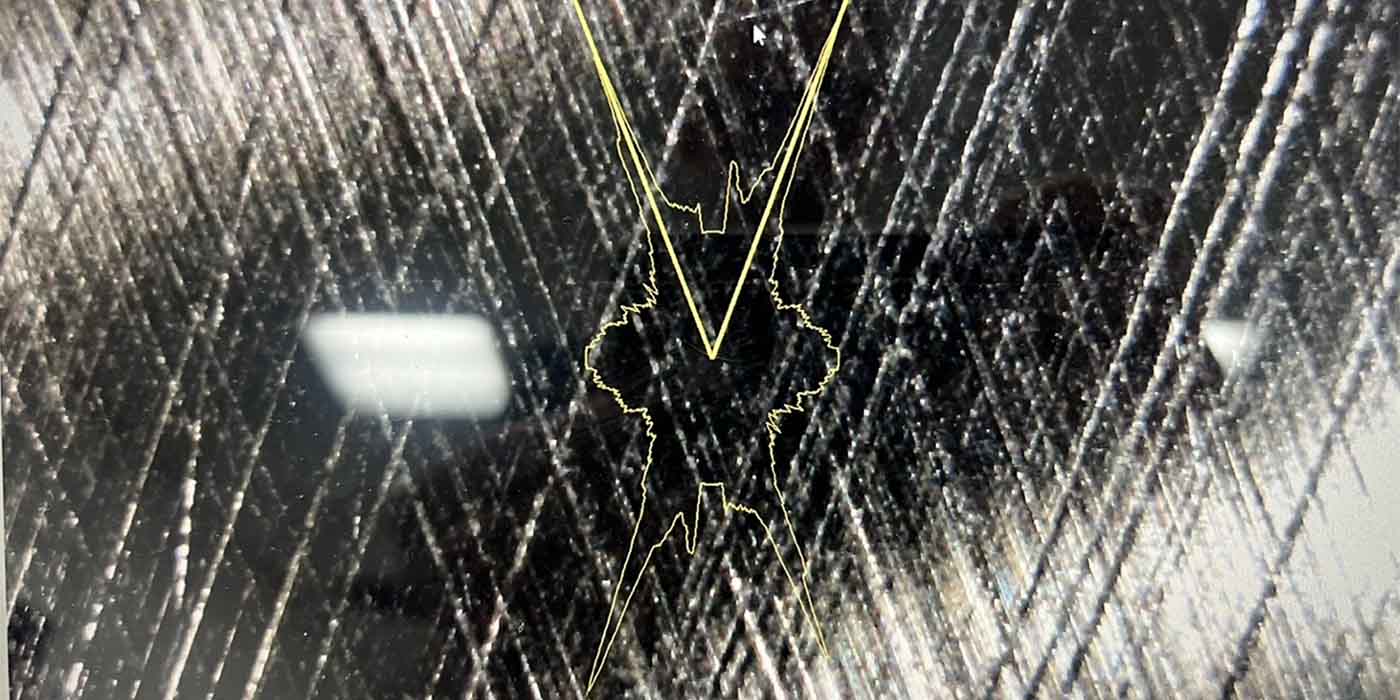

An issue with automated machines is when something is corroded or has contamination on it, whether it be oxidation, oil, paint or whatever is on the surface of a part, it’s not even. It’s different all over the part and no two parts are ever the same. You’re only going to be able to program an automated machine to clean so much.

“To combat this you’d need a manual system right next to that machine that’s a little touch-up cabinet,” says Fred Greis, president of Wet Technologies, Inc. “It still takes up less floor space and streamlines the process.”

Wet Blast Machines

If dry blasting doesn’t sound like your cup of tea, there is another option available, which is wet blasting or wet slurry. Wet blasting is more than just high-pressure water being sprayed. Wet Technologies is one producer of these machines and the company combines media with water.

“Basically, we mix media with water through a durable pump, and we run high flow and low pressure,” Greis says. “We send that through a nozzle or series of nozzles and add compressed air to generate more or less aggression. The media we run are all of the traditional aluminum oxide, glass bead, plastic, ceramic bead, and baking soda.”

In these machines, the water cushions the media. You don’t see as much frictional breakdown from the pumping process as you do with air pressure from dry blasting.

“Every single grain of media that comes out of our nozzle is encapsulated in water,” Greis says. “So imagine it coming in and striking the surface and immediately being picked up by water and carried away. We don’t generate high friction without the water, which keeps abrasives from embedding in the surface.”

Wet blasting does have growth opportunities in this industry, and are driven by three things – zero dust, little or no dependency on chemicals, and floor space, explains Greis. Those three things are driving the wet blast process and this equipment.

“These products are completely green, closed-loop, zero dust, no dust fires, no dust explosions, and we have little exposure to chemicals,” he says. “The machines take up very little floor space.”

Anywhere that you can minimize operators’ exposure to dust, chemicals and fumes, creates a much better and more desirable working environment for employees.

Some of these slurry-blasting machines can separate the broken down media and oils and rust, and then filter the water before it’s sent back into the machine to rinse the parts.

“What we developed is an oil separation system that removes floating and emulsified oils and deposits it all into a separate external container,” Greis says. “This is a big hallmark of Wet Technologies and our closed-loop system.

“We also have a system that does engine blocks. On the other side of the machine there is a two-cubic-foot barrel you can fill with nuts, bolts, washers, and springs. You can control the dwell time, speed of the barrel, intensity, type of media, concentration, flow rate, etc. Those parts come out completely clean with no damage to the threads.”

Wet blast systems do tend to be higher in price, but have certain benefits versus dry blast systems, particularly regarding exposure issues.

No matter how you go about cleaning your engine parts for a rebuild or reman, the most important thing to keep in mind is that you want to deliver a clean, well-functioning finished product – blast media and machines may be the right solution to deliver that. ν