No matter what kind of engine builder or remanufacturer you may be or what applications you build for, at some point in time you’re going to run into a situation where a used engine part or component will come in handy.

You’ll reuse, reclaim or remanufacture it for your specific job. Whatever the reason may be for doing so, that process is how this industry recycles. Engine builders take something that’s otherwise considered junk and broken down and make it like new again, giving it a new life and cutting down on scrap engines lying around.

Whether it’s just how you operate everyday, a cost savings tactic, or a solution to a difficult to find part or unavailable part, there are some useful things to know about how to go about reusing engine parts.

To Reclaim or Go New, That is the Question

The main reason most engine builders will look to recycle parts is for the parts cost savings.

“If you have a cylinder head casting, it could be easy to throw it in the scrap bin and buy a new casting versus remanufacturing that part and bringing it back to like new or even better than new condition,” says Randy Bauer, Gas Engine Division Manager for Jasper Engines & Transmissions. “However, it’s more economical to remanufacture that part than going out and buying a new OE or aftermarket part. Remanufacturers are the ultimate recyclers.”

Most engine builders would agree that cost and availability of a part are the biggest reasons for choosing to go with a used part.

“There’s stuff you can’t even buy anymore for some of these engines and you have to figure out a way, or we are actually having to make parts for some of these older engines,” says Doug Anderson, owner of Grooms Engines.

Anderson uses a “magic threshold” to decide whether he will reclaim a part or not.

“It’s a 65% threshold,” he says. “If I can save a part for 65% of what it costs to buy it new, then I‘m going to do it if I can. There are some things where that’s just a non-issue. You know a rocker is either good or bad, but there are some components where there is a number involved and for me it’s always been 65%. If it costs more than 65% of the cost of new to salvage and try to save something, then I’m going to look more closely at going to new parts.”

So what’s the advantage to reclaiming parts? The engine builder has the part right there. He doesn’t have to find it and source it and it’s going to cost less. But sometimes deciding between new and used parts isn’t so black and white. Frank Owings, owner of Titan Engines, says there is little advantage to reusing certain parts if new replacements are available.

“It’s usually less expensive to replace with new, rather than clean used parts, excluding cast parts,” Owings says. “The smaller one to three man shops have a definite advantage to reusing parts. The man that tears down the engine is usually the same guy that is going to machine and assemble the engine. He has first-hand knowledge of what the parts look like on tear down. He can make intelligent and informed decisions. He is also probably the owner and has control of his own quality control. It’s a different world as compared to production shops.”

Most Common

Reclaimed Parts

With cost and availability on the minds of most engine builders, there are certain parts that are more commonly reclaimed when building an engine.

“On the remanufacturing side of it we go through and we try to salvage the five major castings – crank, cam, rods, block and head,” Bauer says. “There are also some other miscellaneous parts like valve springs, for example.”

Some shops will try and reuse anything that can be refurbished. That means you can bore block castings and anything you can refinish the wearing surface of.

“If wear doesn’t adversely affect the function of the part, you can reuse it,” Anderson says. “You can grind a crankshaft for instance, but you can’t regrind a piston. Here at Grooms we save the block, the heads, the cranks and all of the major component castings and forgings that are there. Pushrods and rockers are inspected and may be reused. Hardware, brackets, bolts and nuts where the prior use hasn’t changed the life expectancy of the part and it hasn’t affected the part dimensionally, is also fair game.”

With recycling being the name of the game, anything from cranks, rods, blocks, heads, valvetrain components, rockers, pushrods, guide plates, roller cams, valve springs and even valves can be reused. And sometimes you have no other option but to try.

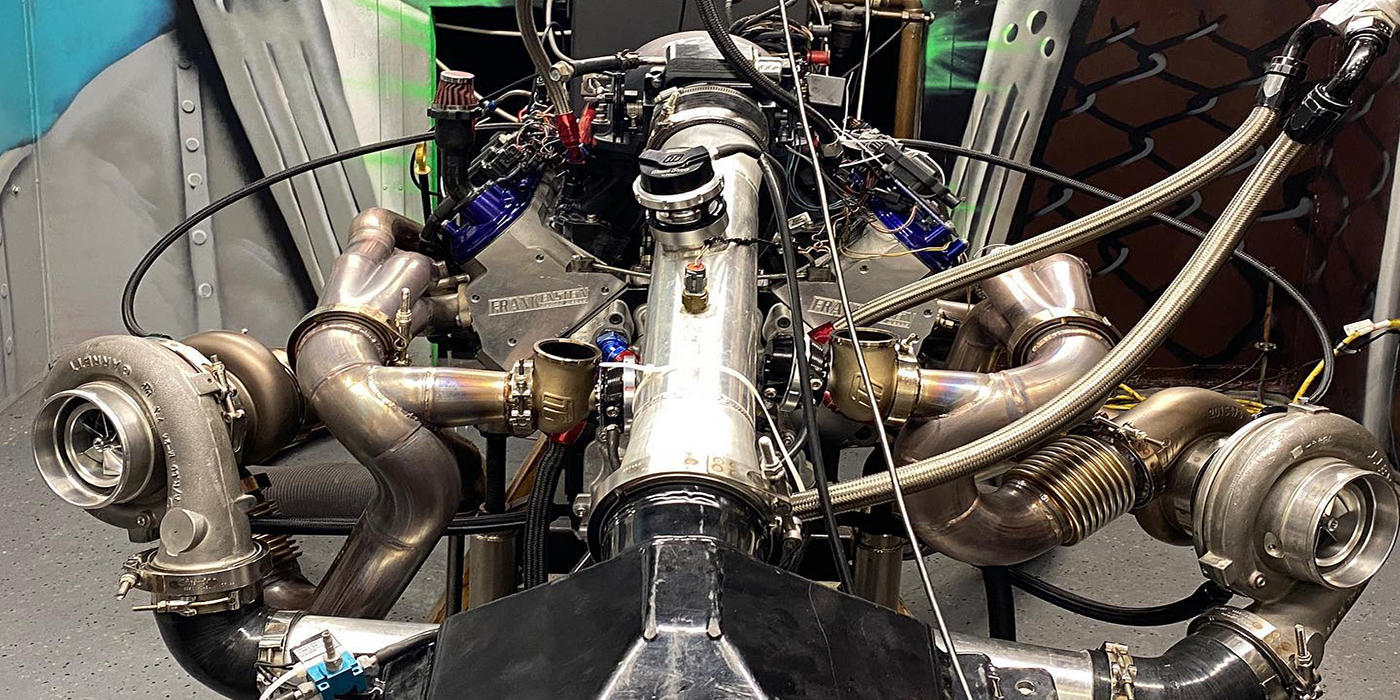

“A lot of the engines we build for customers, aftermarket components are not available,” says Matt Dickmeyer, owner of Dickmeyer Automotive Engineering. “Or with some of the modular Ford engines I have built, OE blocks, cranks and cylinder heads cannot support the horsepower we are building.”

Avoid Reusing these Parts

While many parts and components in an engine are salvageable, that doesn’t mean anything and everything can be used again. There are numerous parts that aren’t suited for multiple time use and doing so would certainly cause harm to the engine. Some of these parts include gaskets and seals, pistons, rings, and bearings.

“All of the wearing parts should be replaced,” Anderson says. “Anything that is called a sacrificial part shouldn’t be reused. That also depends on whether you are a rebuilder as opposed to a remanufacturer. Rebuilding means you fix what’s wrong and if you’re going to reuse something like a piston, then they’re going to qualify the pistons and if the grooves are good and everything’s fine they’re going to clean it up and reuse it, and that’s okay. However, that’s not what we offer as a remanufacturer. We remanufacture the engine and replace or re-machine all the wearing parts.”

Jasper is similar in its determination of which parts to avoid.

“We do not remanufacture valves, pistons, rings, gaskets or anything of that nature,” Bauer says. “We’ve made it part of our business model that those parts are automatically discarded.”

Gaskets and seals are obviously one thing you’d want to replace because they could cause leaking or get destroyed when you try to take them apart. Pistons and valves are up for debate.

“That’s the difference between remanufacturers and rebuilders,” Bauer says. “Some rebuilders may try to use those and will have to mic and check them to make sure they’re all good. There are a number of businesses that actually do reclaim valves for the remanufacturing industry, but we choose not to go that route. We go new on valves and pistons.”

Even though valves can be saved and recycled into another engine, the process is tricky and you have to make sure the valve will qualify for additional use.

“I would never reuse what is considered to be a consumable or any part that falls out of specification with use,” Dickmeyer says. “Components such as valves often get excessive wear on the stems and have been beat up to the point that by the time you grind them, there is no margin left.”

Salvaging a Part

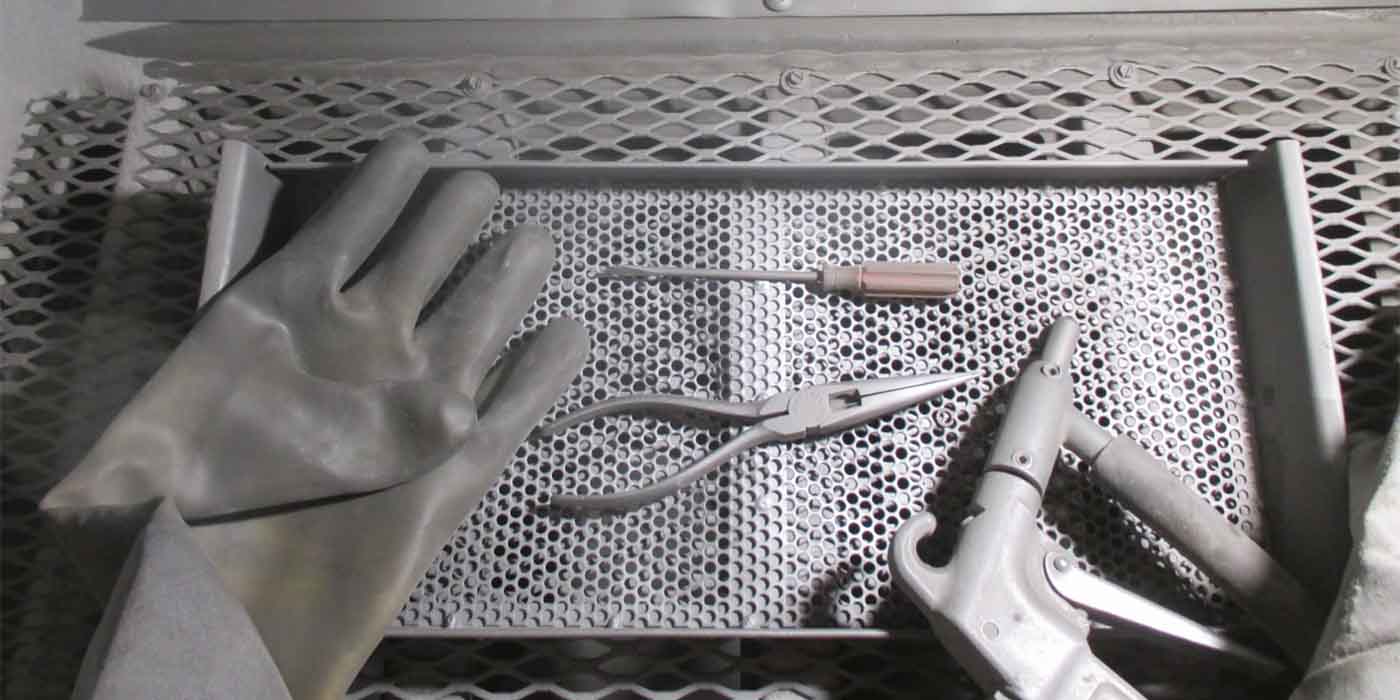

So you’ve selected what parts you can reclaim and which ones you can’t. With the parts you’re going to reuse, reclaim or remanufacture, how do you go about the process properly? There are several things you’ll need to make sure you do, and the first is to get the part clean in order to inspect it.

“The parts have to be cleaned, prepped and inspected to make sure there’s no visible damage,” Bauer says. “After that, depending on the type of part that you’re working on, you may have specifications you have to read out with a micrometer or you may have to put a part under a specialized test.”

Before an operation such as Jasper’s will remanufacture a part and say that it’s good enough to go back into an engine, they make sure it meets stringent quality standards through various testing methods. Anything that doesn’t meet those parameters or specifications is kicked out.

“With valve springs for instance, we actually put each individual spring onto a load cell and pressure test it to get a reading on what the spring rate does through its travel operation range and make sure it meets specification to an OE spring,” Bauer says. “If it doesn’t it gets kicked out and if it does it’s deemed good.”

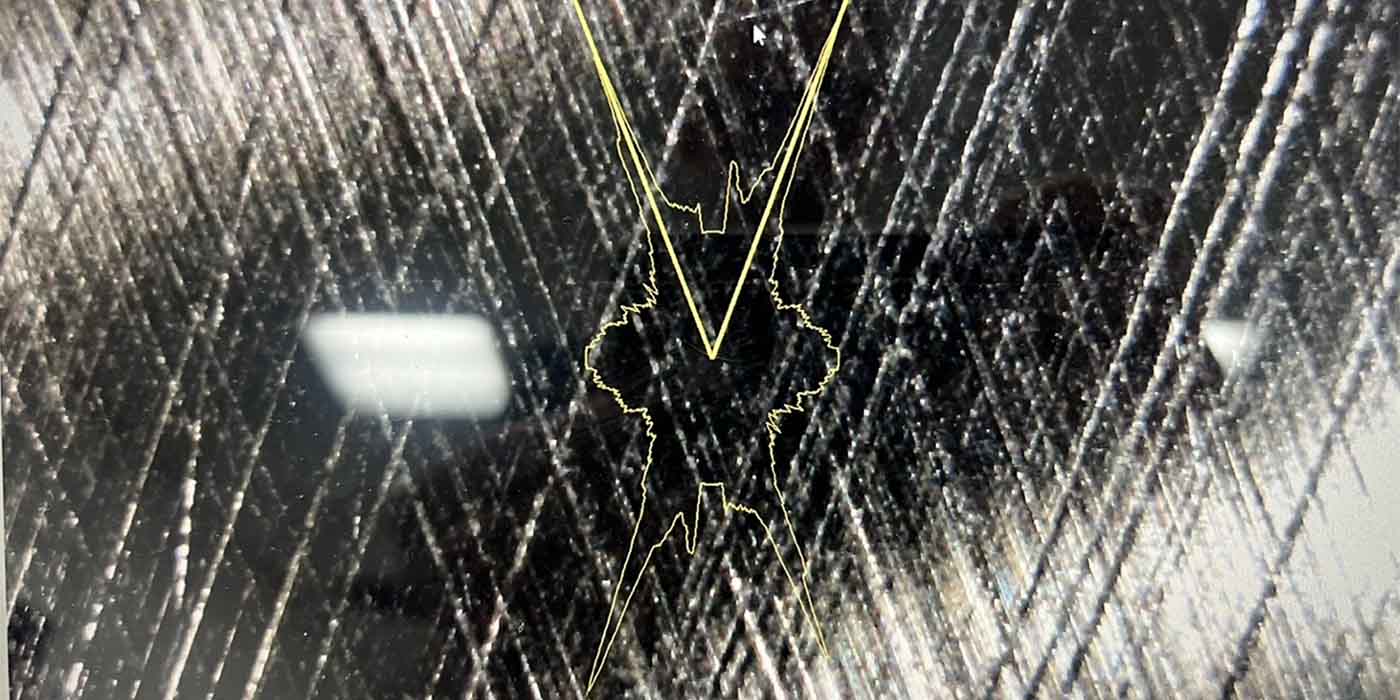

When looking to reclaim an engine part or component, properly qualifying the part is the most crucial step once it is cleaned up.

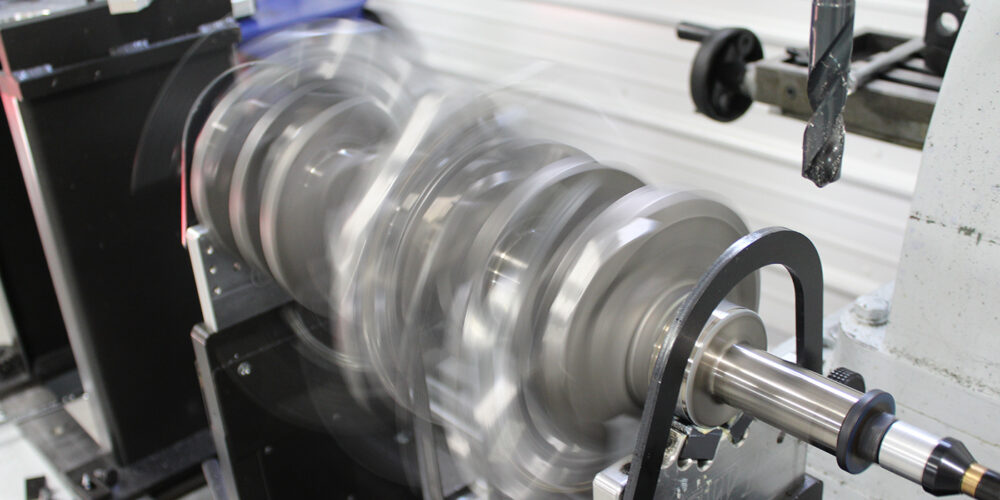

“You’re going to look for cracks and/or damage,” Anderson says. “Then it’s a matter of grinding it to size, doing your machining and inspecting the size after it’s machined. With blocks you bore them and cranks you grind them and the rods you recondition them.”

If you have a part that has too much wear, reusing it is a risk you should not take. If it’s been abused or misused then that may well disqualify it. But if it qualifies in terms of fit, form and function then there’s little difference between new and used.

“You try to err on the side of ‘I won’t take a chance’ as opposed to taking a chance, but on a block, I’ll do almost anything I can to save it,” Anderson says. “I’ll put eight sleeves in it. Whatever you have to do to save the major castings, you do it. If that means welding a crank or spray welding rods, I’ve done it if it means salvaging parts you can’t get or can’t afford to buy new.”

You never want to put hours into a part to later find out it won’t work. These types of mistakes are not only costly, but can make you look like a bonehead to your customer. Make sure to measure every component at disassembly to confirm whether the components are a good candidate for reuse and then perform all machining operations to restore precise measurements and precise clearances.

“If the parts are sufficiently checked, machined and tested prior to installation, it can be a cost saver and time saver,” Dickmeyer says. “But if parts are not correctly inspected, it can cost you the entire engine. Sometimes by the time you do it all and do it right you can see that you didn’t really make as much as you had hoped. But if something goes wrong, you not only look like a fool, you have to do it all over again at a total loss.”

Others agree that sometimes reusing parts and going with new can be a tougher decision than it may appear to be.

“The cost difference between cleaning and replacing is sometimes a very thin line,” Owings says. “The labor involved and the inherent liability sometimes outweigh the feasibility in reusing parts.”

Engine builders have to remember too that there are environmental issues when cleaning old parts. The chemicals have to be disposed of and tanks cleaned. However, the environmental impact on producing a new part is just as harmful to the environment.

“It’s not really a perfect solution,” Owings says.

Another thing to keep in mind is your shop’s manpower. If you’re large enough to have a trained person in place to inspect all reusable parts, it’s more feasible. Smaller shops don’t always have the available resources for good inspection programs.

“We would all like to think that we could increase our bottom line by reusing parts that have no surface cost,” Owings says. “This is always a plausible thought, until you start to add up the cost of cleaning, inspecting and selling the customer.”

The costs of going new or trying to reclaim a part can indeed vary. But more often than not, there is a benefit to salvaging a part for another application.

“A cylinder head for example, I can salvage and reclaim it versus going to buy new,” Bauer says. “If it’s an aluminum head late model, you might spend anywhere from $300-$1,000 for a new one. Or a crankshaft, I know there’s cases where crankshafts will run $500-$1,000. If I could reclaim it in some fashion and remanufacture that crankshaft that money is saved. I may have some additional labor tied up into it and maybe some chemical costs, tools or supplies involved, but typically those saved dollars are significant.”

Application Matters

There is little doubt that trying to recycle parts can be a cost saver and time saver when done properly with parts that qualify for reuse. However, the specific application you’re trying to build for can also play a role in determining whether you go new or used.

Performance-wise, you can reuse many of the same components, but it depends on the performance level you’re reaching for.

“If you’re going to a street performance 350 horsepower engine, then the crank and rods and all those components can be reused just as they can on a stock rebuild and remanufacture,” Anderson says. “If you start reaching for horsepower, then all of a sudden rules change and you can end up using everything new (cranks, rods, camshafts) because of the grind on it, and some people even use new blocks in some of the applications. It depends on what you’re asking the engine to do.”

As an engine builder, your first decision is whether or not a component will withstand the forces that the engine will operate at.

“Engines like the Chrysler 4.7L V8 are powdered metal rod with a cracked cap,” Dickmeyer says. “If they are out of round, you can bore and hone them to a larger OD bearing shell. But in my experience, they are still prone to failure. So in similar applications it is easier and better to buy new components. Other times, the level of power and performance customers are seeking doesn’t exceed the durability of a used component.”

Conclusion

At the end of the day, the decision is up to you and your customer whether you recycle parts or not. However, recycling is the name of the game in the remanufacturing business. Millions of BTUs of energy are saved every time an engine casting is recycled. Some applications will require new parts due to the demands of the engine, but there will always be a time and place to recycle engine parts. n