As with everything in the engine rebuilding industry, technology has dictated how each aspect of the process has changed and how it has advanced. This also applies to something as seemingly simple as gaskets, and more specifically, Multi-Layer Steel (MLS) gaskets and block and head surface preparation.

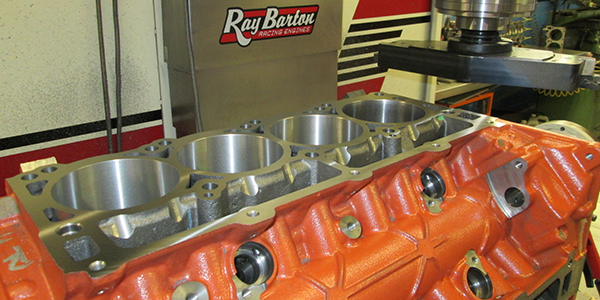

MLS gaskets have come a long way in the past 10 years. These advancements in gasket technology have led to MLS being used on production cars, and engine builders such as Ray Barton of Ray Barton Racing Engines in Robesonia, PA has even used MLS gaskets on engines up to 2,000 hp.

Gaskets of yesteryear were made essentially of a fiber-like material, which allowed them to adhere to and seal surfaces that weren’t very smooth, but in turn would cause issues with higher horsepower engines.

“You couldn’t make big horsepower on those gaskets because they would always fail,” says Barton. “Years ago, the older decking machines would leave threads on the block when you machined them, and the gasket guys would say it was alright because it grabbed the gasket. Gasket surface prep has totally changed these days. When I started out you could practically catch your fingernail on the surface of the blocks right from GM and Mopar, and it was fine because of the material gaskets used to be made out of. You can’t get away with that these days. The racing engines are making double or triple the horsepower when I started out in 1969-’70 when a race motor made 500 hp. Now a street engine makes 900 hp.”

Today’s MLS gaskets require more surface area and an as-smooth-as-possible finish to seal properly.

“You can never get a surface too smooth,” Barton says. “With MLS gaskets, the smoother you get the block or head the more surface area you have to seal against the gasket. You don’t have a million bumps or ripples. Every time you have a bump or ripple you actually have less surface area for the MLS gaskets to sit. With the coatings on the new gaskets they want it as flat as you can get it.”

That flat finish comes from having the proper machinery. As with the gaskets themselves, the machines too have gotten more advanced due to technology dictating the necessity for smoother finishes.

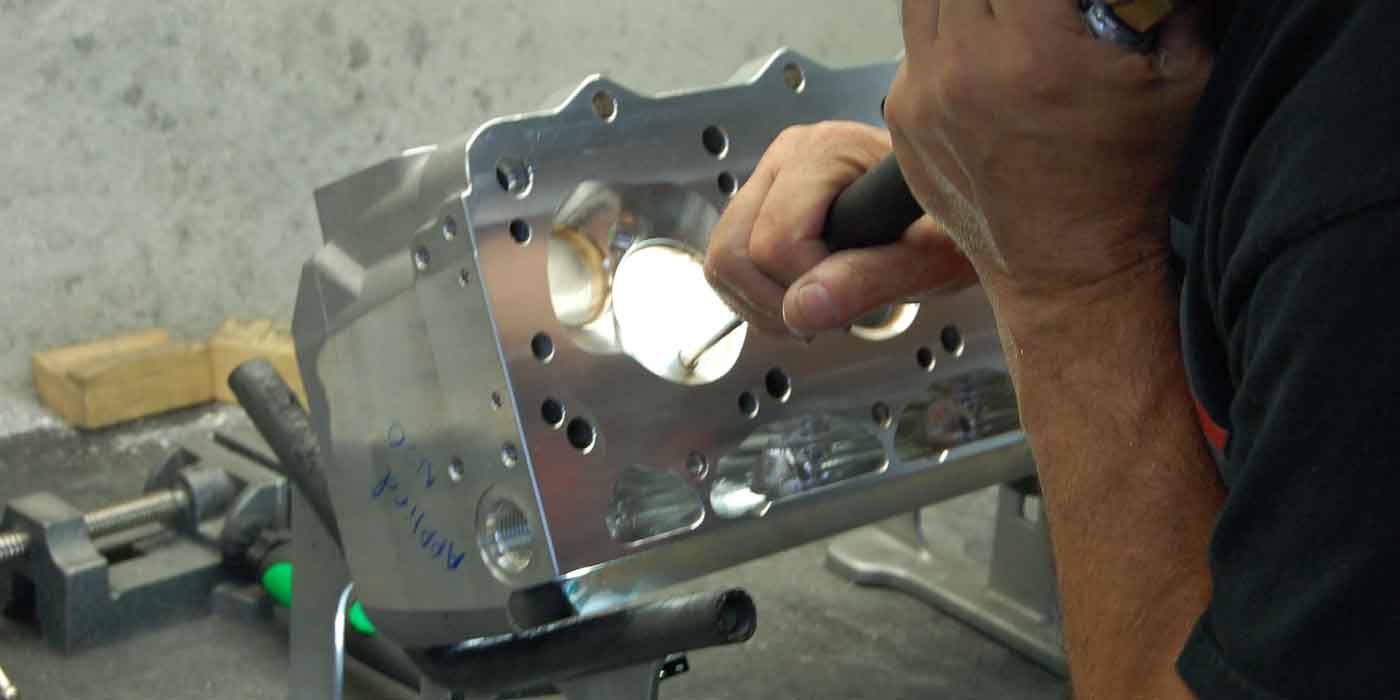

“At Ray Barton Racing Engines we use two machines for surfacing blocks and heads,” he says. “The first is an HBS2100, which is no longer made by Sunnen, but still works so well that I get offers all the time from people who want to buy it. The second is a new Rottler F69A. Both machines are very heavy-duty and don’t vibrate or deflect when machining hard or CGI blocks or heads and leave a mirror finish. They both use single CBN cutters. The machines cost $200,000, but you definitely speed up efficiency and accuracy.”

Many older machines had no way to adjust the feed rate. This meant that what you cut is what you cut – you couldn’t change the finish. This was acceptable with old gaskets but not with today’s MLS gaskets.

“Those older and smaller machines will deflect, vibrate or bounce off the part instead of cutting the part because they don’t have the weight,” Barton says. “If this is the case for when you do gasket surface prep, you’re more likely to experience a failure. Some guys have machinery that they’ve had for 50 years and that just doesn’t make it nowadays.”

Once you have a block or head in a newer machine, the job only takes about 15 minutes. However, it might take you an hour to get it to that point.

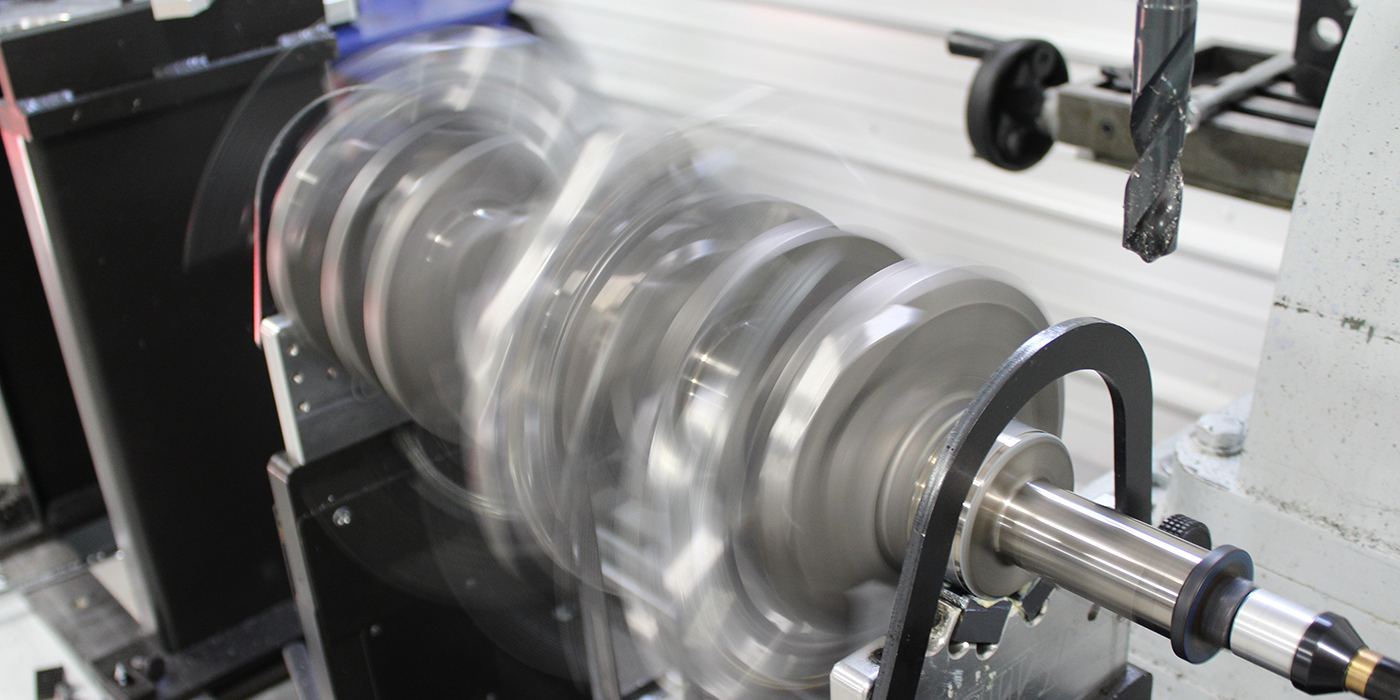

“We always line hone the block first and then deck the block square to the line hone where the crankshaft would sit in the block,” he says. “Once the part is in the machine it’s more or less a matter of pushing a few buttons to get the proper surface finish. Using other similar machines could take you a couple hours to really get it right.”

At Ray’s shop, his guys use a tolerance of .001˝ per 12 inches. He says many new blocks and heads are way out of spec and need to be corrected or they will fail in a race application.

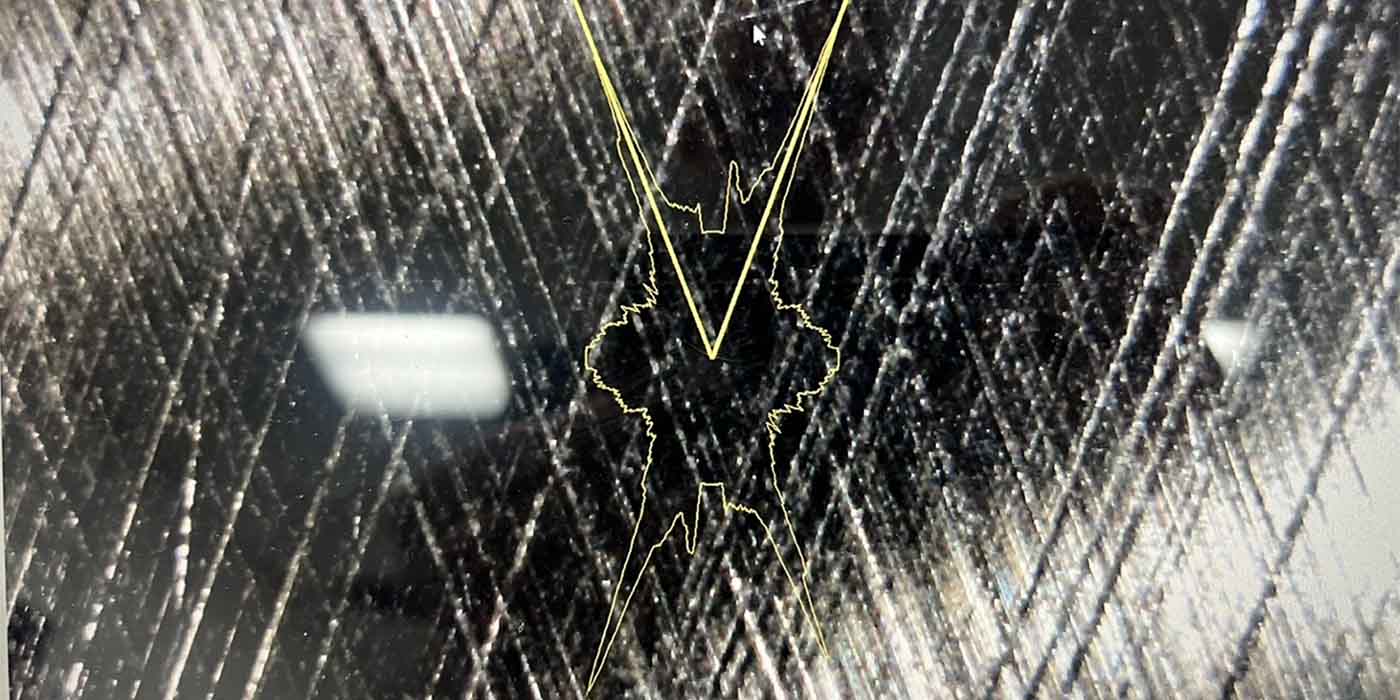

“We shoot for a finish of 15 Ra or finer, which gives more surface area for gasket contact,” he says. “If I can get it any smoother, it would be even better. At 15 Ra you can see your face in the metal because of the mirror finish.”

Most gasket manufacturers recommend a minimum of 50 Ra or smoother for MLS gaskets. Using a profilometer allows you to measure surface smoothness.

“We use a Mitutoya SJ301 profilometer with a tape printout to record Ra finish for each engine build,” Barton says. “If you don’t use this tool you can’t measure how smooth your surface is – you can only guess. When your surface isn’t flat and you have tiny bumps or grooves in the finished surface that’s when you experience failures. Gas will escape through the surface and the gasket because there isn’t anything that will fill in those voids if it isn’t perfectly smooth.”

Those voids in the surface will make your engine prone to leakage and gasket failure.

“Gasket failure can lead to head failure or block failure,” Barton says. “The blow-by can start to eat a groove into the block. It all starts with the gasket failing first and that can lead to catastrophic problems.”

To avoid those catastrophic failures, you’ll want to finish off the gasket application using quality fasteners and hardware, and use the proper torque sequence to secure the gasket. If you do so you should have zero problems. In fact, MLS gasket technology has come so far these days that Barton has even used gaskets three or four times in race motors before having to replace them. That level of functionality is due to excellent machine work, attention to detail and a smooth block or head surface. ν