Look back at the events in your life an examine how timing has played a part in the outcome. When you showed up at party and met the girl who would eventually become your wife? When you stayed late at work and missed the 18-car pile up on the interstate?

Even without realizing it, your personal timing has played a huge role in your – and others’ – life. Try as you might, though, you can’t do a lot to control events and situations. If your timing is off, well, you’ll just have to live with the consequences, good or bad.

Under the hood, however, it’s a different story. Timing is everything and being off even the slightest amount can have damaging, even disastrous effects. You CAN control the timing in an engine and here are some basics with regard to the differences and distinctions between timing belts and chains in the aftermarket.

How important is accurate engine timing? According to Engine Builder Technical Editor Larry Carley, things that happen faster than the blink of an eye are critical.

“Opening and closing the intake and exhaust valves in precise synchronization with the up and down strokes of the pistons requires very accurate timing. At idle, the time interval between valve openings for each cylinder is about a fifth of a second. At 5,000 rpm it is about two hundredths of a second. In a four-stroke engine, the intake and exhaust valves open and close every other revolution of the crankshaft, so the cam only turns at half engine speed. That is why cams have big gears on the end and crankshafts have little gears. The drive ratio is two to one, so at 3,000 rpm the cam is turning at 1,500 rpm.”

Valve timing affects fuel economy, emissions and engine performance and, as with every other part of the engine, can only be properly maintained through a precise relationship between many different parts.

If a timing belt or chain breaks, or the cam drive gears fail, the cam stops turning, the engine loses all compression and the engine stops running. A cam drive failure can also cause expensive valve damage in “interference” engines that don’t have enough clearance to prevent the valves from hitting the pistons if the cam stops turning or jumps out of time.

Interference engines can be found in some Acura, Honda, Hyundai, Infiniti, Isuzu, Nissan and Porsche applications, as well as some Audi, BMW, Mazda, Mitsubishi and VW applications. Certain domestic engines from GM, Ford and Chrysler have the same design, but whether it’s interference or not, a timing belt or chain that breaks, stretches or is otherwise damaged is never a good thing.

Belts or Chains? How Do You Choose?

Both belts and chains have advantages and disadvantages in each application. According to an aftermarket supplier of engine components belts offer lower weight, lower cost and less noise. They are wider than chains, however, increasing the overall engine length. Belted engines need more room under hood. They also require replacement, typically at 50,000 to 90,000 miles, depending on the belt’s construction.

Timing chains, with their thinner width, reduce overall engine length and are more durable, requiring no scheduled maintenance. They do make more noise, have higher weight and higher cost. Replacement chain kits can cost hundreds more than replacement belts, especially on OHC engines. This makes rebuilds of chained OHC engines very expensive.

However, according to another leading timing component supplier, over the past 20 years belt applications have been fading out. “The Achilles heel of belts has always been the recommended change interval, which, for the most part, remains around 60,000 miles. A timing belt is considered an internal engine component, mission critical and most manufacturers offer powertrain warranties of 100,000 miles and they do not want a mission critical component that can’t make it through the warranty period. Timing belts are not cheap to replace. The job can cost well over $300, more or less in the same realm as a timing chain.”

There’s not much to do with respect to inspecting a timing chain. Modern applications should go well beyond 100,000 miles. But if the engine needs to come apart for any reason, the chain guide wear surfaces should be checked. Wild wear patterns would indicate a chain system problem. Most systems are engineered to keep the chain under control while the chain wears, but if those limits are exceeded, problems will show up and the wear surfaces are a good indicator. With regard to belts, they are also usually hidden. It’s best never to gamble beyond the manufacturers recommended change interval.

Another aftermarket supplier says for today’s medium-size to smaller automotive engines, belts are still a viable option. Part of the engineering equation here is the distance between the cam and crank – the longer that distance, the more likely the OE will choose to use a chain. As engines continue to be physically downsized, belts are seen as the more cost-effective choice by many manufacturers.We recommend checking belts beginning at 50,000 miles and then at 10,000-mile intervals thereafter. With chains, you’ve got greater durability as long as the engine is well maintained. Look for chain stretch, and be sure the slack side of the chain can’t be moved more than half an inch.

Timing chain sets are far more expensive, both at the OE level and within the aftermarket. Plus, in a replacement situation you’re typically replacing only the belt, whereas with a chain setup you need to replace the chain and sprockets. Regardless of style, however, all of our experts agree that it’s absolutely imperative for the aftermarket part to follow the lead of the OE manufacturer. Each engine’s unique physical design and performance requirements dictate the timing technology used.

What changes do engine builders need to understand about modern timing components?

Again, say experts, it’s important to follow the OE design. Also, make sure you have the engine manufacturer’s instruction manual and carefully follow the timing set manufacturer’s installation instructions. There are fewer and fewer three-piece timing sets coming out at the OE level today; we’re now seeing up to 15 pieces in a set for a DOHC application, for example. On some of these sets, the windows on the cam sprocket’s timing sleeve play a role in actuating the valvetrain. Because the requirements of each engine are now so specialized, says this industry spokesman, rebuilders must be certain they are replacing the OE set with a technology that mirrors the OE design, and this is true for tensioners, guides, rails and other components, as well.

Says another technical expert, the biggest change in timing sprockets has been a move from machined cast iron to sintered (powdered metal). Most sintered sprockets require no machining which eliminates extra manufacturing steps and also produces closer tolerances from one part to the next.

“I don’t know about racing,” he says, “but one of the biggest issues we see are rebuilders installing the wrong cam sprockets. Many engines have camshaft timing sensors that read a reluctor wheel on the cam sprocket. The OE’s tend to make subtle mid-year changes to cam sprockets. The wrong sprocket will still bolt up to the engine but it won’t run.”

Recognizing the applications and the changes made to them are critical. Gear-to-gear setups are more common in older GM and Ford light- and medium-duty truck engines. These applications typically had a compressed fiber cam gear mated with a cast iron or aluminum crank gear. The fiber style cam gear was used to help reduce NVH, but the teeth were susceptible to breakage.

Today’s aftermarket replacements are typically metal-to-metal, with an aluminum cam gear and a cast iron or steel crank gear.

Holding to the true definition of a “timing gear,” says timing component manufacturer, they are almost extinct. “By true definition, I mean gear (mates with another gear) vs. sprocket (runs with a chain). We still sell iron, aluminum and fiber (phenolic resin) replacement gears for the inline 4- and 6- cylinder engines made back in the day, but almost all modern engines are chain driven. There is however, a growing number of engines that use balance shafts to dampen the engine vibrations. These shafts often use a pair of gears. We offers many balance shaft gears, but often they don’t wear all that much and their replacement is not as common as other timing components.

What kinds of other timing issues do today’s engines face? What about in the performance/racing arena?

There haven’t been a lot of changes in technology for your standard performance 350s, 318s and 302s, which are the applications that continue to dominate Saturday night racing, explains a manufacturer located right in the heartland of racing. When you step up to a 5.0 Mustang and other, more sophisticated engines, the racer-tuner is basically locked out of most internal engine repairs and upgrades.

When choosing a timing set for a performance application, pay attention to the material used in the sprockets – you need steel for the best performance and durability. Also step up to a roller-type chain; the increased performance is worth the added investment.

Another benefit of some timing sets is the ability to vary the timing to one-degree increments, rather than the traditional three degrees.

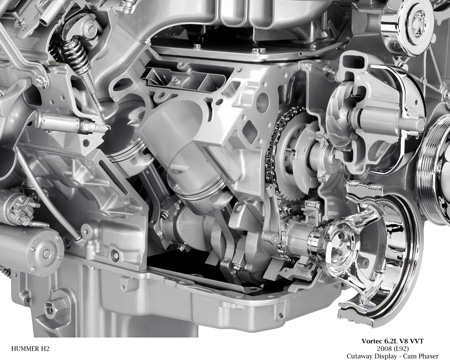

How have variable valve timing and other technological advancements impacted the aftermarket timing industry? One expert who explains that his company has been involved with variable valve timing since the late ’90s on an OEM level says almost all modern engines use a vane type cam phaser (VVT) to improve emissions, fuel economy and performance.

“For example, the GM V6 found in most of the GM vehicles uses 4 phasers, one on each camshaft. At the OE level, they are expensive, about 10 times the price of a sprocket, but the benefits are worth it. There is also a subsystem of oil delivery to make the phasers shift properly. It makes oil pressure become a key factor in controlling engine timing.”

The days of the three piece kit (cam sprocket, crank sprocket and chain) are rapidly coming to a close, he explains. Our North American OEM’s are making very few “cam in block” engines anymore. A typical cam drive system now needs sprockets, chain guides, chain tensioners and multiple chains (cam bank one, cam bank 2, balance shafts ….) Obviously these systems are more expensive and the engineering is more challenging.

“Timing components are no longer simple,” he concludes. “They do more things, like carry cam triggers and target wheels to let the engine ECM know where each of the cams are with respect to their rotation. One of our day-to-day challenges is to keep our catalog up to date with the right parts as these things migrate from year to year.”

Thanks to the aftermarket suppliers including Avon/Pro Gear, Comp Camps, CV Products and Melling for contributing to this article. Special thanks goes to Hunter Betts at EngineTech, Rick Simko at Elgin Industries and Jeff Hamilton at Cloyes Gear for their contributions.