I often hear customers ask about the difference between a sleeve and a liner. It’s an understandable question. Automotive guys call them sleeves and diesel guys call them liners. And while they may be used for similar purposes, the perception of what they do may be very different among different groups.

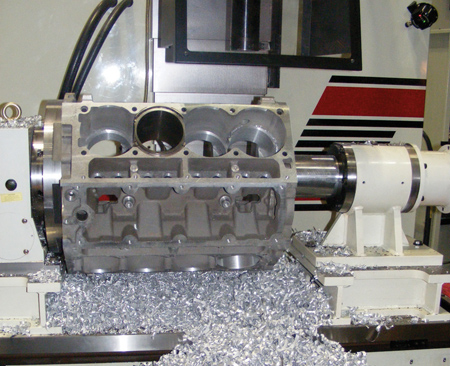

Many automotive enthusiasts understand that sleeves are used in the repair of damaged cylinder bores in

engine blocks or in heavily modified four-cylinder engines for racing. While this may all be true, the fact of the matter is they both are the same. The term “liners” is often used in relation to cylinder bore repair in a diesel engine. Either way, it is still understood to be an item that is machined and inserted into the engine’s block as a way to repair the cylinder bore.

But, what other way would a sleeve and or a liner be used, other than to repair, when dealing with today’s modern power plants?

Most cast iron automotive engine blocks do not require sleeves because the iron is hard enough to resist piston ring wear. This is important because the purpose of the cylinder is to seal the piston rings. Over time, as the engine components become worn, a rebuild will be inevitable. But cast iron engine blocks allow the cylinders to be bored and oversized pistons installed.

The only time that a sleeve is required is when the cylinder is cracked or there is not enough material in the engine’s casting for the cylinder to be bored. In either situation, the cylinder that is in need of repair can be machined for a sleeve that will be interference fit, which means that it will need to be pressed into the cylinder block.

The same can be said for mid-size diesel applications. Diesel blocks are usually thick enough to be machined, so the only time a sleeve should be needed is when the cylinder is cracked. But diesel engines are also more expensive to repair. Most of the time, when a diesel is in need of repairs, it is because there is a problem with one or more of the cylinder bores.

Damage to the bore comes from extreme temperatures that may distort – or melt – the pistons. When the piston becomes distorted to this extreme, it will gall the cylinder bore leaving melted aluminum behind. Generally this is referred to as a “burnt hole,” and in most instances is found in only one cylinder. The engine block can be machined to accept a replacement sleeve, repairing the bad cylinder and requiring only one replacement piston, saving the rest of the block.

Of course, engines aren’t only made from cast iron. Today, even daily drivers have lightweight aluminum engine blocks. These aluminum blocks are manufactured with a “cast-in-place” dry sleeve, in which the cylinder sleeve is placed into the mold when the aluminum cast is poured to form the cylinder block. This can be a very cost-effective design, but can restrict the potential of the engine’s power. This sleeve design will be perfectly reliable for the purpose it was designed, but frankly, it typically won’t be able to take the stress it would face in a high horsepower environment.

One example of this is the GM LS1. The factory sleeves may not be able to take the heat in some high-performance applications.

Another method used to produce some production aluminum engines is to use no sleeves at all. Instead, the aluminum cylinders are coated with a nickel silicone alloy or some other special plasma coatings that resist wear and offer longevity, durability and a improved ring seal.

Sleeve Construction

Most sleeve manufacturers today form sleeves by a centrifugal casting process. Molten metal is poured into a rotating mold in which the centrifugal force drives the material toward the walls as the mold fills. The finished sleeve is easy to machine and offers great strength and durability compared to ductile iron.

Sleeve manufacturers offer a wide range of bore diameters ranging from 2” to 8.5” that can range up to 24” in length. Sleeve thicknesses are available from 3/32” and 1/8” for bores up to 5-1/8”. For some special applications, sleeve wall thicknesses of 1/16” and 2mm can be achieved.

Special iron alloys are used for each manufacturer’s castings. Each has been formulated to provide the supplier’s ideal blend for ease of installation with trouble-free boring. The sleeves contain alloys found in today’s plated cylinders that will not peel or flake. These alloys offer superior tensile strength with efficient and quick heat transfer.

Fit and Finish

One thing that needs to be addressed is the thermal efficiency of a sleeve and the type of block into which it is installed. It all comes down to interference fit. Because sleeves are flangeless, a tight fit keeps the sleeve from moving up and down in the bore when the engine reaches operating temperature.

When a sleeve is installed into a cast iron block, the process is fairly simple and effective. The sleeve, which is mostly constructed of ductile iron, is pressed into the cast iron block. When pressing a sleeve into an iron block, there needs to be an interference fit between .0015” to .002”. As the engine operates under normal conditions, the cast iron sleeve can transfer heat from the cylinder into the cast iron of the engine’s block. Coolant is circulated through the engine block and surrounds the cylinders to effectively remove heat from the installed sleeve.

However, cast iron and aluminum dissipate heat differently, due to a different rate of expansion. For an aluminum block, there needs to be an interference fit of .003” to .004”.

When a sleeve is installed into an aluminum cylinder block is where a potential problem can begin. In an aluminum block, heat may be removed from the aluminum cylinder block but not properly transferred from the cast iron sleeve into the aluminum bore. The sleeved cylinder can overheat, causing damage to the piston and rings because of this poor heat dissipation between the different alloys.

It’s very important to understand when installing a sleeve, that the

engine block must be machined as round and straight as possible. Concentricity is very important to eliminate bore distortion. Most sleeves are very accurate in outside bore dimensions. If the block is not truly accurate by being bored round and straight and the sleeve is pressed in, piston clearance and ring seal will become a problem. If there is a poor fit with a lot of gaps, the sleeve can run the risk of moving up and down in the bore. Also, if there are gaps from poor machining, there will be hot spots in the cylinder from poor heat dissipation into the engine block.

Wet Sleeves

When it comes to dealing with engine blocks like GM’s LS engine with the cast-in-place sleeve, replacement can be a problem. If the original sleeve becomes worn, the cast-in-place sleeve will have to be machined out. When you do this, there will not be enough material to support a replacement sleeve. The alternatives are to machine out the cylinders entirely and convert the block to a wet sleeve design.

Heavy-duty diesel engines have always integrated a wet sleeve design, often referred to as a liner. The liner can easily be understood as a removable cylinder bore. In a diesel engine, the liner is designed with a flange at the top that fits into the deck of the cylinder block.

There are no cylinder walls in the cylinder block; the liner is the cylinder wall. On the outside of the liner, there are machined recesses at the top and bottom that house rubber O-rings. These rubber O-rings seal the liner at the top and bottom of the engine block from coolant leaks. This allows engine coolant to pass around the cylinder liner to remove heat from the pistons and rings yet not leak coolant into the oil pan or cylinder head.

The rebuild process of a heavy-duty diesel engine is typically referred to as an “in-frame” rebuild, because most of the time, new components such as bearings, gaskets, pistons and rings can be installed without engine removal. The frame of the vehicle is simply used as the engine stand. During the in-frame, once the pistons and rings are removed from the cylinder, a special tool is used to pull the liners out of the engine block.

When new liners are installed, they come already fitted with new pistons, connecting rods, and rings ready to be inserted into the cylinder block. Most heavy-duty rebuild kits come with internal components pre-fit and ready for installation for the application so there is no need for liner boring or piston fitment.

If your application is for hardcore performance or a severe-duty, a design has been invented that allows you to machine the block to accept a patented sleeve design known as Modular Integrated Design (MID). In the MID process, the block is machined so the sleeves can be siamesed and nested into the block to form a solid deck surface.

The sleeve flanges are held in tension, reinforcing the upper deck area. The beauty of this design is not only strength, but each sleeve can be replaced if needed. Each sleeve is fitted together by integrating them side-by-side to lock in the entire cylinder block.

The sleeves are a wet design just like a diesel in which water flows around the sleeve and not the cylinder block. This wet design promotes water flow from the block to the cylinder head to give stability to the cooling system. There is also water flow around the flange of the sleeve by ported water flow called Swirl Coolant Technology.

The MID process has a specific sleeve design for each engine application. For each engine design, the manufacturer will model the sleeve according to cylinder head and combustion chamber shape, with increased water flow to areas that are subject to the most heat. Heat transfer will also be

directed to a set of “registered fins” integrated into the sleeve for the application. While heat can be translated into energy, high resident heat in the combustion chamber can lead to detonation. A range of MID sleeve designs that cover many performance applications is available.

Keep several things in mind when thinking about sleeves and liners. Whether their purpose is going to be repairing an OE application or to go all out in the restructuring of the engine block, they have to be able to perform a number of tasks. They should be concentric in shape to offer good ring seal and wear resistance. The sleeve or liner will need to be manufactured with an alloy that is going to provide an anti-galling property that will offer a sliding surface for the rings and be able retain lubricant and transfer heat.

Therefore, when needing to install either of the two, you will need to consider the application as to what the sleeve or liner will be used for and the work you’ll have to do to install them. It may not be a simple process, but it can give an old block new life.

Very special thanks to the companies that contributed to this report: Darton Sleeves (www.dartonsleeves.com); IPD?Parts (www.ipdparts.com); L.A. Sleeves (www.lasleeve.com); and Melling Engine Parts (www.melling.com). For more information on cylinder sleeves and liners, visit our exclusive online Buyers Guide for additional product and contact information.