Like most racers, I was not keen on tech officials and some of the rules they enforced during my long drag racing career. But in 2004, as my racing career was winding down, a young friend named Chris McMahan, Operations Manager of RT. 66 Drag Strip in Joliet, IL, talked about having me come work for him on his tech official staff. That bizarre idea intrigued me – so I did it.

That decision caused some humorous grumblings in the drag race fraternity. “Good grief! That is like giving Billy the Kid a badge!” I was also compared to Jesse James (though, sadly not Alexis DeJoria’s husband).

But then many realized, who would be better? A real racer who ran a lot of outlaw venues, alongside a lot of rule benders would be good for both sides of the sport. I am sure most racers have bent some rules. I ran with several great racers who did, and were never found out.

I had a few tricks myself, but these were mostly in the area of updated belts and net, etc. I am sure others did as well, which is probably why the date-punched tag system replaced printed dates. When expiration dates were only stamped ink, all that was needed was an eradicator, a proper size stencil kit and a steady hand.

Oh, the stories I could tell! I know a racer whose car required extra tubing. So as not to add weight or chance a negative chassis reaction, he tacked in the couple new required bars, made “Dum Dum” look like weld and painted over it. After the certified sticker was given, as soon as he got home, he would remove the extra bars.

Others cheated with devices to trip the win light sooner and get a better ET. Some would hide illegal nitrous systems. And some of us used a restrictor in the spark plug hole to lesson the cubic inch when “pumped.”

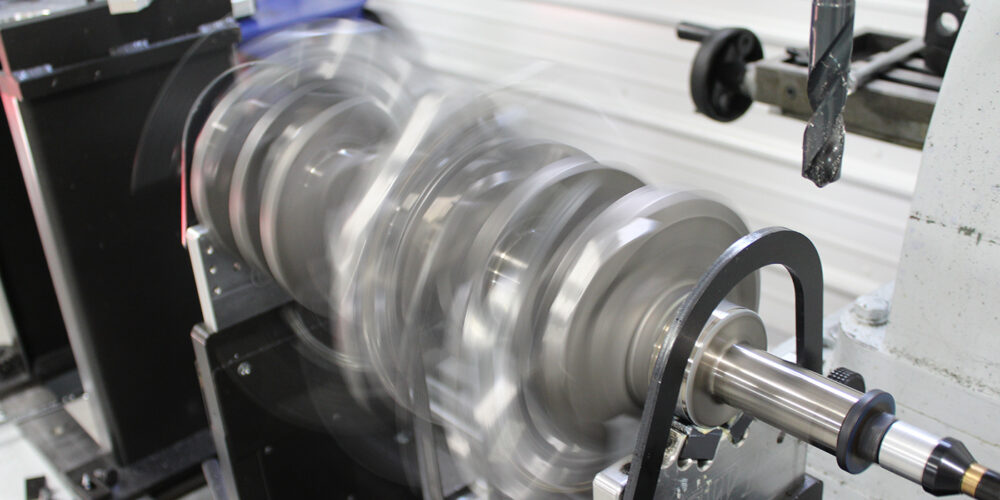

I only tried cheating to enhance my performance once, using that spark plug restrictor. It was during the ’70s in the early Pro Stock days. Entries were weight- factored a certain number of pounds per cubic inch – and not equally. The canted valve Cleveland, which I ran then, earned the highest factor. In AHRA, my Pinto was factored at 7.2 pounds per cubic inch. Most entries back then were de-stroked small blocks, running high rpm. I had a 339 cid Cleveland that I spun over 11,500 RPM. To acquire that, we used super lightweight pistons, tool steel wrist pins the thickness of conduit, lightweight aluminum knife-edged rods, and huge spring-breaking roller camshafts. Breaking valve springs was a huge problem back then; one would break every few runs.

For a backup bullet, I had a 342 cid. For the “no cubic inch rule” UDRA Circuit, and match racing, I had a stroked 383 cid Cleveland.

The legal venue I was racing Pro Stock in back (the AHRA Ozark Nationals in Springfield, MO) then had an eight-car field. It seemed I was always getting bumped to number five, only by a couple hundredths. I knew a couple of Pro Stockers, always making the top half, who would bump me to that position, were cheating.

The elimination ladder was: 1 ran 5, 2 ran 6 and so on. For several events in a row, being number 5 qualifier, I had to run number 1, and of course without lane choice. Number one was always the unstoppable Lee Sheppard. Needless to say, I would be a first round loser.

So to even the situation, I made a bad decision. Instead of blowing the whistle on the cheaters, who I had match race business with, I decided to beat my cheating friends at their own game.

I got a cheater spark plug restrictor when I bought some used Cleveland parts from a retiring Pro Stock racer. The device was sold by JC Whitney as an adaptor to keep a spark plug up from an oiling hole. However, when the exiting orifice in the device was drilled out to 7/32˝ we got some interesting results.

The next event, I had my match race 383 cid engine in my Pinto. The procedure to check cubic inch was fairly simple and predictable. The tech official would come around to the racer’s pit and pick a cylinder at random to “pump.” Then he would go on to another racer, and come back later. On that chosen cylinder, the rocker arms had to be loosened and the spark plug removed. The measuring device was a long, clear, calibrated tube with a plunger in it made by a company called P&G. When the tech man came back, he would hand me a hose like one used with a leak down tester, and have me insert it into the spark plug hole.

Cleveland heads, sporting aluminum high port exhaust plates, confined in a Pinto, made the spark plug holes unseen. I would screw the hose into the chosen spark plug hole and then the official would connect it to the huge vial. Then the engine would be cranked as when checking compression. Where the plunger stopped, that calibration would transfer on a chart to exact cubic inch.

Only this time when the tech was gone, I had installed the restrictor tightly in the selected spark plug hole. When he came back, as normal, I put in the hose.

Low and behold, when my 383 was pumped, the cubic inches measured 342 a common de-stroked Cleveland size, and the size of my other small cubic inch engine. I removed the hose – and when all was clear, I also removed the restrictor and replaced the spark plug.

Remember the weight factor I mentioned earlier? Those 41 “fewer” cubic inches equate to 295.2 fewer actual pounds. At 342 cid, my weight with me, only had to be 2462 lbs. The tech installed a sticker on my door window for the scale man to see. After every run, weight was checked.

Being an old car we could only get my Pinto down to 2550 lbs. But in reality, with 383 cid (383 X 7.2 would be 2,758 lbs.), we were still cheating by 208 pounds.

You know what they say about best laid plans. After two qualifying attempts, the Ozark track was just not hooking up. We ended up putting all of those 208 pounds plus 20 more back in the Pinto. We were now at 2,778 pounds.

On the next qualifying attempt, wow! The Pinto loved that weight with the bigger engine. We ended up the number-two qualifier. Unfortunately, after winning the first round, I was protested. The tech wanted to pump me again so I ’fessed up. In my defense, I pleaded that we had added the proper weight for the 383 inches and even showed them the device I used to restrict the original cubic inch reading. However, since I had not gone back to tech to get recertified before qualifying again, I was thrown out anyway.

Man, I felt like something the cat dragged in. I never did know for sure who blew the whistle on my attempted cheating, though I heard through the grapevine that it was someone I knew for fact was cheating using the same kind of restrictor device. After that experience, I never tried to cheat on a performance rule again.

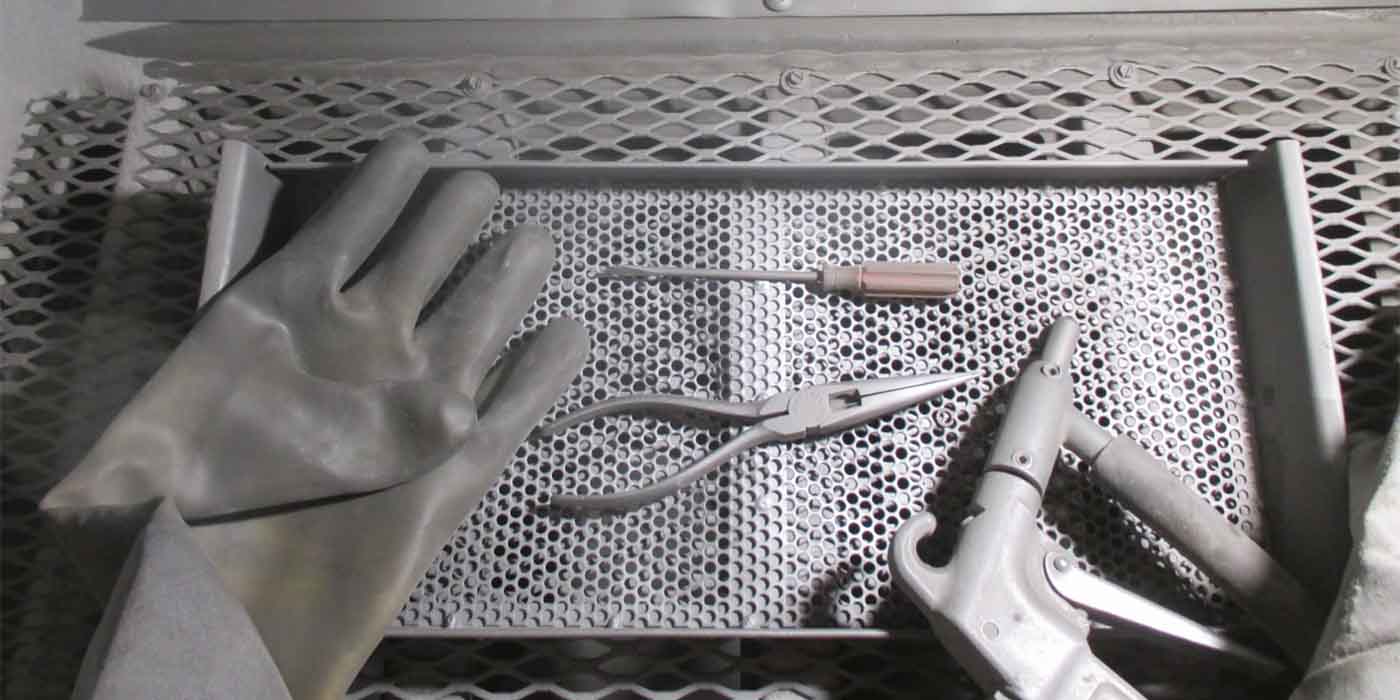

Most of the tech I have done at Rt. 66 Dragway since 2004 has been checking for safety issues with Test and Tune participants, bracket racers and exhibition vehicles.

The required safety equipment is relevant to elapsed time and MPH. For NHRA, which sanctions Rt. 66 events, cars dipping into the 13-second zone, require a current Snell/SFI approved helmet. Go quicker than 11.50 and many more safety rules apply, including an SFI 5-point harness, roll bars and SFI Jacket. The 10s require more. Go in the 9s or over 135 mph and a license and certified chassis are required, as well as more personal safety equipment. After 8.50, at 7.50 and under 6 second cars require much more at each level.

For engines in bracket cars, there are many different legal combinations. While there aren’t many performance regulations there are some electronic regulations. We check engines for leaks, mountings, breathers, fuel and cooling systems; a 16-oz. radiator overflow is required on all participants.

The newer muscle cars have caused a stir in tech. With advent of such quick factory cars 2008 and newer, NHRA now allows 10 second elapsed times, if the factory car is pure stock. This is hardly a problem: we recently had a new factory 2015 707 hp Challenger Hellcat go 10.87 on DOT tires.

As far as the professional door slammer drag race classes go, NHRA limits for Pro Stock are 500 cid and minimum weight is 2,350 lbs. NHRA Pro Modified, with nitrous, is 910 cid at 2,475 lbs. Super Charged is 426 cid at 2,600 lbs. and Turbo Pro Mod cars are 426 cid at 2650 lbs.

NHRA Pro Stock has the most involved engine performance rules. The engine must be a naturally aspirated, single-cam 90 degree, pushrod V8. Like I mentioned above, the maximum cubic inch allowed is 500 inches. Aftermarket block and head castings must be NHRA approved, but no billet heads. Maximum cylinder bore spacing is 4.900˝. A NHRA approved dry sump oiling system is allowed.

Heads can be ported and polished and may have special port plates on the exhaust or intake side, but not both. Port plates cannot be more than 1.5 inches wide, and may not be recessed into the head more than the plate width. Two NHRA approved 4-barrel carbs are allowed.

All large components (valve covers, intake manifolds, headers, heads, blocks, etc.) and all moving engine components are restricted to aluminum, steel, iron, titanium, magnesium or other conventional alloys. Carbon fiber, Kevlar, ceramics, composites, beryllium or other exotic materials are prohibited.

The minimum weight for Pro Stock pistons is 460 grams; wrist pins must be at least 135 grams; connecting rods must weigh 480 grams each; minimum intake valve weight is 90 grams and exhaust valves must exceed 80 grams.

Pushrods are required to be steel. Titanium valve springs are illegal for safety reasons: they show no warning signs of fatigue, even if constantly checked. They can just suddenly blow apart.

Pro Stock engine rules have basis in both safety and cost rationale. At one time composite rods, and even valves, were used. The expense became outrageous.

Being on the other side has been very interesting for me, and for others as well, I am sure. Some think I have too much empathy for the racer. That may be true: the last thing I want to do is keep a driver from racing or testing. When I doubt questions about the rules, I show the person the exact page in the rule book, even if I am sure of it.

However, whether the racer or I do not like a rule, my comment is always the same: “My job, just like a police officer, is to enforce the rules – I do not make them.”

Because here’s the thing: enforcing these rules keeps us both safe, because there is one very important issue about tech that many folks are not aware of. When the driver and I both sign that tech card we are both liable.