While the victor of multiple racing events usually gets all the attention, what about that unsung hero under the hood? After all, a driver is nothing without a dependable engine that can go the distance. What follows is a case example of how an engine builder can empower a talented driver to take home multiple trophies, and includes some specific tips on tailoring an engine setup to a wide range of applications.

While the victor of multiple racing events usually gets all the attention, what about that unsung hero under the hood? After all, a driver is nothing without a dependable engine that can go the distance. What follows is a case example of how an engine builder can empower a talented driver to take home multiple trophies, and includes some specific tips on tailoring an engine setup to a wide range of applications.

Regarding his competition credentials, Danny Popp is a two-time winner of the Optima Ultimate Street Car Challenge (OUSCC), and plans to jump into the fray yet again this fall. As of this writing, he’s already won four of the eight qualifying events. More recently, he took home the title at the 2015 Holley LS Fest (reclaiming his title from 2013).

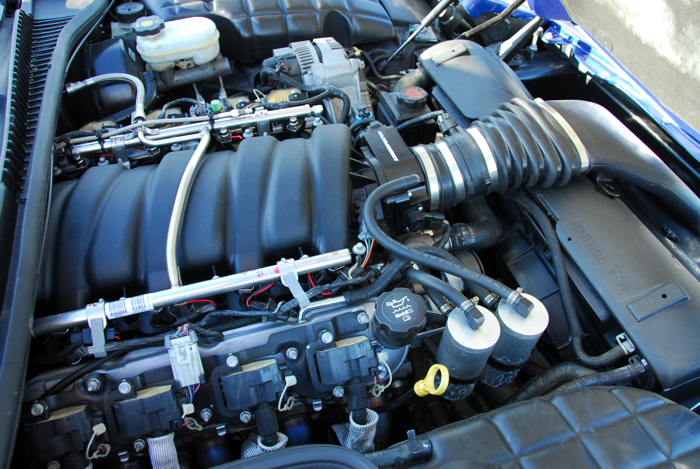

Since these events include a mix of venues, his 2003 Corvette Z06 needs to be well rounded, performing effectively in a number of areas. He competes on both road and autocross courses, plus drag strips and a speed-stop braking event. So clearly a temperamental mill with a loping idle would be out of place. It has to be carefully balanced in order to be able to perform well on different track types, yet still drive on the street with the manners of a pussycat.

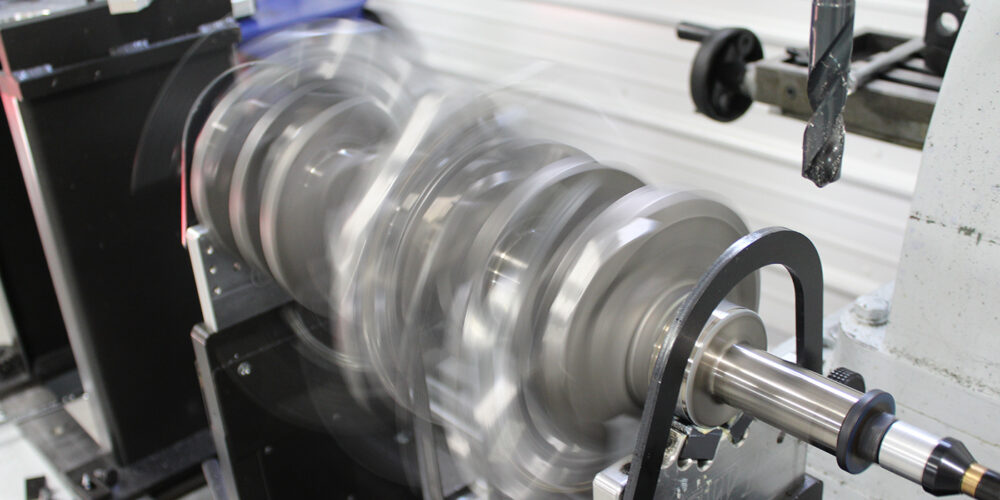

Popp’s mill of choice is a name well-known in performance and competition circles: Lingenfelter. The engine fitted into his C5 Corvette (preferred over later-model Corvettes for its lighter weight), is not a high-strung hot rodded mill. Instead, this 388 cid LS7 is destroked, going from 4.000 inches stock to 3.625 inches using a Callies Magnum crank. With destroked crank, the pin in the piston can be relocated to keep it out of the ring land. Also, to reduce friction, the pistons have shorter skirts and a lightweight 3mm ring package.

Since the powerband is not about peak output, but optimized for a flat torque curve instead, the cam is actually a somewhat milder GT19 bumpstick, with a more open centerline of 118 to 121 degrees. This setup provides a smoother idle and better drivability (whether on the Vegas strip or dragstrip). The cam also features a custom grind with a ramp profile that has more lift for its duration, which is done exclusively for Lingenfelter by Comp Cams.

In addition, Lingenfelter spends a lot of time testing and massaging the flow of LS7 heads on Popp’s engine, which are CNC-ported and hand-finished in the bowls and chambers. The titanium intake valves are factory parts, but the exhaust valves are stainless steel (instead of sodium filled) as they are better suited to big lifts and high rpm. The intake manifold topping the heads is a stock (but ported) LS7 unit, because an MSD intake will not fit under the cowl.

All told, this component configuration drops the torque by about 50 to 70 lb./ft., in order to minimize wheel spin either off the line or accelerating out of a turn, for more precise handling. Delivering 587 rwhp (655 hp at the flywheel, and 585 lb./ft.), it’s no slouch in the horsepower department, but it’s custom tailored for track duty in a number of ways.

As Lingenfelter’s Vice President of Operations Mike Copeland explains, “We have to consider several variables when we build a race engine: application, vehicle weight and the specific needs of the driver and car.”

Backed by a Tremec TR-6060 6-speed transmission built to Lingenfelter specs, along with a 3.91 rear end, this powertrain setup allows Popp to stay in first gear while threading through the cones, running up to 68 mph at 7,400 rpm.

But this rev level has recently been upped to 8,200 rpm, requiring a change to a solid-lifter camshaft. “That increases valvetrain stability and the lifters weigh less,” Copeland points out.

Turning the reciprocating mass at a significantly higher rate also requires additional care in the tuning of the components. “We do a lot of Spintron testing of components,” he adds. “There are different issues – critical issues – to address at higher rpms.” All of which requires careful calibration and balancing of all the components used.

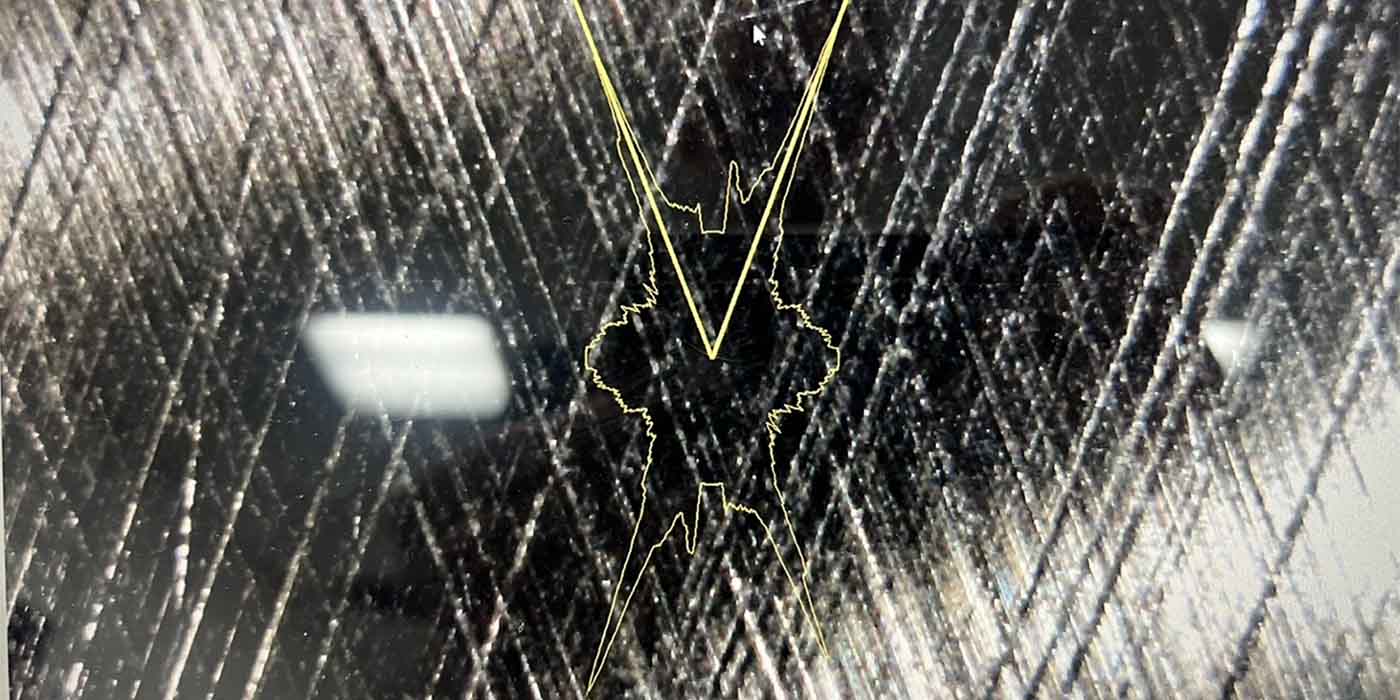

These parts also have to be customized for the drivetrain. Since the Tremec TR-6060 6-speed transmission has a special gear set with custom ratios, the output shaft is upgraded from a 27 spline to a 30 spline. Which means the adapter mount between the transmission and rear axle has to be modified to accept the larger bearing for the 30-spline shaft, and the pinion has to be modified to accept the larger spline. Lingenfelter has the pinion spline changed at RPM Transmissions, which uses an EDM to cut the new spline.

With this customized drive line, “There’s a 1,500 rpm drop between shifts,” Copeland notes. “So we have to keep the torque output high to prevent lugging, and operate in those phases.”

Another difference in Lingenfelter’s custom comp-grade engines is the use of dry-sump oiling. About 20 cars in Optima Challenge use Lingenfelter engines, but only six have purpose-built race motors. For those customers in particular, Lingenfelter focuses heavily on durability and reliability to ensure the engines survive the rigors of competition.

“That’s one of the biggest challenges,” Copeland admits. “Almost all of our time is spent on that aspect so racers can beat it like a rental. Popp is a very aggressive driver. We never have to tell him to use the upper rpm range. He’s always on the ragged edge.”

This emphasis on survivability pays off, though. All told, Popp’s driving experience at the Holley LS Fest, which included demanding trials of drag racing, autocrossing, and the 3S challenge, was basically uneventful: “We never opened the hood.”

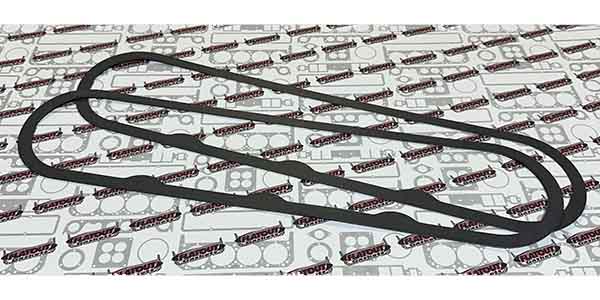

Conscientious maintenance contributes to this sort of reliability, of course, which includes valve spring replacement every few months, as they tend to lose pressure under heavy use. So Lingenfelter technicians regularly run the valvetrain to check lash.

In addition to all the attention paid to the hard parts, Lingenfelter has the logistical reserves to keep Popp on the track. When he first started competing, he built his own engines, since he’s a technician at a Chevy dealership by trade. But now, having a professional engine building company the size of Lingenfelter handling the mechanicals, he can focus on driving duties instead.

“Competition programs put some serious demands on the company,” Copeland says. “It’s very expensive to run a racing engine program, and you need a lot of resources. But we can supply a new engine within a week.”

Commenting on the value of all the time and effort spent on the Optima Challenge, Copeland adds that, “The lessons we learn in this series contribute to the development of our own performance parts line. Being able to compete against some of the best performance cars in the country on the nation’s most prestigious racetracks helps us research and test how new component technologies will perform under a multitude of challenging conditions.”

That puts a new spin on an old saying, competition doesn’t just improve the breed – it hardens it when doing battle on the track.