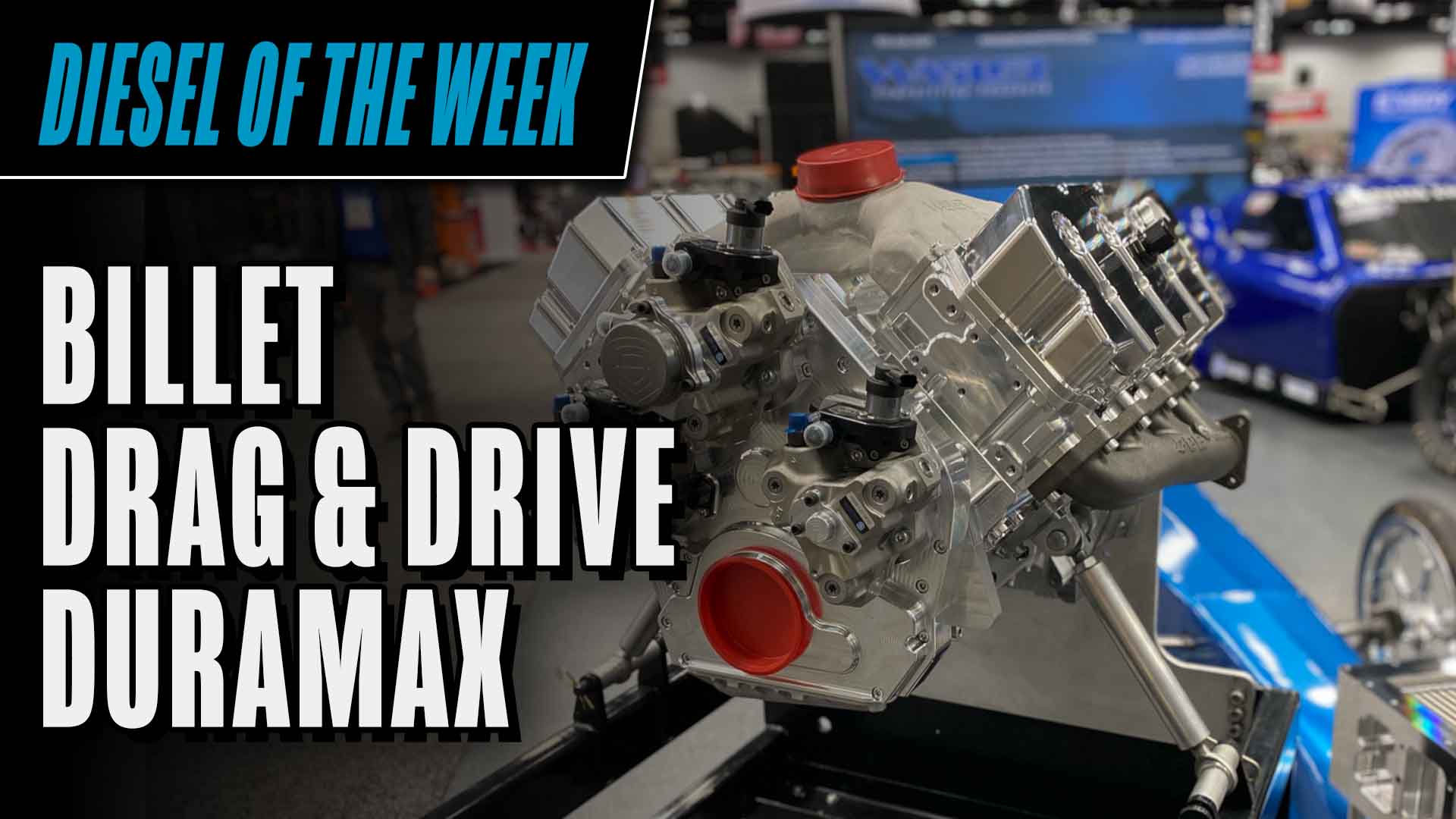

I recently freshened Pat Fitzpatrick’s champion 567 cubic inch big block Chevy Super Comp engine. Pat is a serious player. He was IHRA World Champ in 2000 and second and third in IHRA Super Comp points the next two years.

Then in 2007 he won Super Comp at the NHRA Indy Nationals, running against the number one-rated Super Comp racer in the finals. Not an easy task just to win SC, and to do it at Indy against the best there is make it an even more impressive feat.

Fitzpatrick told me he had borrowed that 567 cid Chevy from a close Super Comp friend just before he won Indy in 2007. His friend then gave him the engine for winning the championship. Wow! Some contingency! Some friend!

In NHRA competition, there are three fixed ET Sportsman classes: Super Street (10.90), Super Gas (9.90) and Super Comp (8.90).

Using Super Comp class as an example, a field is filled during qualifying by who runs the closest without “breaking out,” in other words, running quicker than the allowed 8.90 seconds elapsed time. Red lights when qualifying do not disqualify the run.

Eliminations use a heads up Pro tree start. “Super Class” drag racing is similar to bracket racing, except everyone in their respective class has the same breakout.

During competition, a red light or crossing center line/touching the wall is an automatic disqualification. Do that and your opponent then is the winner, even if he or she breaks out. If only one of you breaks out, the one who didn’t (assuming there was no foul) is the winner. A double break out winner is determined by who breaks out the least. In a pair with no fouls, the winner is the one who gets to the stripe first. Breakouts are also allowed on bye runs.

Those three Super Classes also use a delay box and trans brake like Super Pro, Top Sportsman and Top Dragster.

In the opinion of some fans, the fixed elapsed time Super Classes using delay boxes and throttle stops may not be the most exciting drag racing to watch. But there are a lot of racers involved in them. I’ll admit that I never paid much attention to the fixed index Super classes until I became an official at Route 66 drag strip in Joliet, IL, 11 years ago.

During my prime years of racing, I was involved with Pro Stock and Pro Modified classes. In that type of racing I manually set the line lock and lit my bulbs, with the throttle on the floor to the staccato tune of the soft touch rev limiter. Then when I saw a glint of a yellow flash, I popped the clutch and simultaneously released the line lock-or hand brake.

Throttle stops and delay boxes were all foreign to me. I knew a throttle stop was a device placed like a spacer or nitrous plate under the carburetor, and at least understood the basic concept.

Several years ago I became friends with Fitzpatrick. Freshening his Super Comp engine, and getting detailed information from him about the science of his class was quite an education for me. A serious Super Comp engine is its own entity – so is the racer!

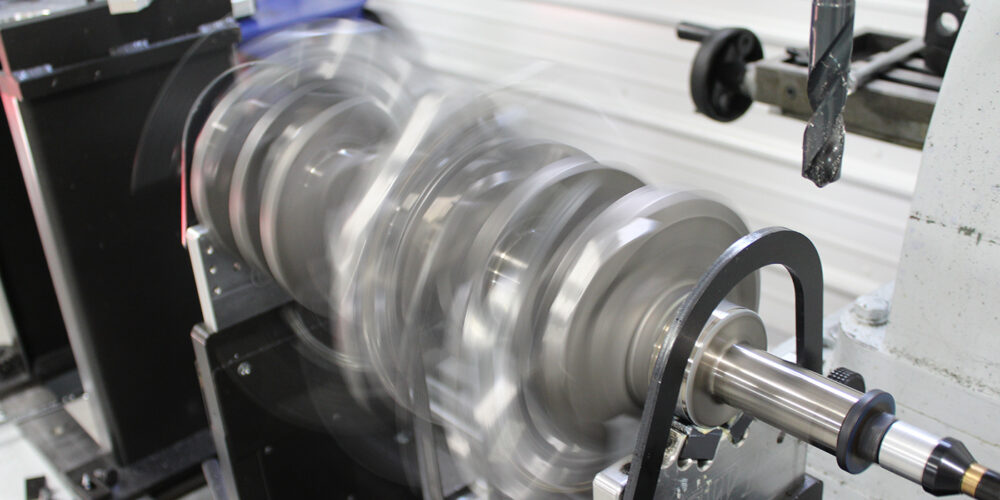

Like a Super Pro bracket engine, durable parts – like steel cranks, good H-beam rods, special forged pistons, shaft-mounted rockers, an external timing belt system, good flowing heads with severe-service stainless or titanium valves and Pro Stock-type valve springs as well as special oiling and pan – are needed to be able to go many rounds.

Fitzpatrick says he has gone as many as 300 runs before freshening the engine. That is remarkable for engines of that caliber. Try that in Pro Stock or Pro Modified with engines that cost much more and undergo constant development.

For Super Comp, a special grind camshaft, and how it is dialed in, is one of the keys to keep the engine flexible at all RPMs.

The Super Comp engine also needs more performance development than a normal bracket engine. It needs to make at least 1,000 horsepower or more. A reliable, smooth flexible fuel delivery is most important. Most Super Comp racers use a single, specially prepared, Dominator-style carb.

Like Fitzpatrick’s, most Super Comp entries are dragsters. Being lighter than a sedan, a dragster can accelerate and decelerate quicker. Granted, that much horsepower in a dragster run all-out would mean it can go much quicker than 8.90; more like low to mid-7s. But all that reserve power is needed for the final delay recovery to blast to the stripe. It’s near the end of the run where decisions to take the stripe under power or dump it are made.

What most drag race fans, enthusiasts and even racers competing in other classes do not realize is how sophisticated the fixed ET classes using throttle stops are. As I said, I did not realize it myself until Pat showed me how the throttle stop works.

The throttle stop dates back to at least 1986 – of course, it has been highly refined over the past 30 years. According to Fitzpatrick, former Super Comp champ Steve Cohen was instrumental in the early development of throttle stops. Cohen now runs Top Dragster.

The three Super Classes are the only ones allowed a throttle stop. In the beginning of the Super Class fixed index racing history, racers had to set up the car and physically control their driving in order to run as close to the index as possible. When the throttle stop entered the picture, things changed drastically. Now the racer can program that device to hesitate and resume to be close to the index.

When watching the Super Classes, you’ll notice the car will make an initial launch, then bog down, then go again; then it may hesitate and slow down again mid track only to recover and charge all-out for the finish.

That is the throttle stop device in action. As I mentioned before, racers can adjust and tune them to their best advantage. Super Comp racers are also allowed an automatic shifting device.

But it’s not just the throttle stop that’s important. The type of torque converter is very important as well. It needs to be able to provide smooth throttle interruption and recovery to keep consistent elapsed times.

Classes like Super Street, Super Gas and Super Comp offer drag racers a way to run at a lesser expense than some of the other Sportsman and especially Professional classes that demand constant performance development.

This doesn’t mean that Super Class cars are cheap – don’t get me wrong, the Super Class cars are expensive, and the best equipment is used for the effort. But once the investment is made and the car is doing its job, the rest is up to the driver and not simple cubic inch development money and twelve person crews.

Those Super Classes also create lot of business for the performance industry. Engine builders like us as well as countless product entrepreneurs benefit from them. And the sanctioning bodies and track owners benefit from all the entry fees.

Driving them takes some unique skills. My friend Carl Root is another serious Super Class player. He won Super Gas at the Route 66 NHRA Chicago Nationals a few years ago, and if I were ever to consider racing Super Gas or Super Comp I would definitely need Carl and Pat to teach me how.