This is the first installment of a three-part series on marine performance engine building. This series will look at this market from three different perspectives, the “meat and potatoes” refresh, turning big power into bigger power and then culminating with a look at the mega power that pushes 50-foot offshore endurance racers to over 200MPH.

The Performance Refresh

Our first stop is at Gellner Engineering in Cleveland, OH. Gellner’s roots date back to the drag racing scene of the ’50s and they have been deeply involved in marine performance since the seventies. Second generation builder Dean Gellner began working in the shop at age 13 and 30-something years later is turning out some of the hottest engine builds in the region.

Dean’s resume doesn’t stop in the engine bay – he’s also spent time in the cockpit of a raceboat as well. He’s a guy with an encyclopedic knowledge of not only what it takes to make it to the finish line, but also back to the dock or the trailer at the end of the day.

In this installment, Dean is going to take us through the ins and outs of an everyday performance rebuild. In many ways, these builds can be as challenging or more than a full-on racing engine. These engines are manufactured to meet a price/performance point and that always involves compromises. Dean’s goals for these projects goes beyond restoring these engines to baseline. He aims to increase reliability and nudge the performance needle a bit, while avoiding killing the customer’s budget.

Mom & Pop

Many small businesses are described euphemistically as “Mom & Pop” operations. Gellner Engineering truly got its start that way. Sam Gellner, a budding drag racer in the ’50s and ’60s, got his start in the high-performance industry by selling small block Chevy gaskets out of his trunk at the races. These were gaskets made by Sam and his friend, Joe Hrudka in Joe’s father’s shop.

Joe, with Sam’s help, went on to found the gasket manufacturer Mr. Gasket Company, and later, Sam, with wife Carol, opened Gellner Engineering in the Cleveland suburb of Brookpark. Since 1970, Carol’s voice is the one you hear when you call the shop.

To say that Carol “knows a lot for a girl” would be an unimaginable understatement. More than a few have left the Gellner shop having learned both a few things about racing engines as well as about making assumptions after their conversation with the always-cheerful Mrs. Gellner. With Sam’s passing a few years back, Carol and Dean, with long-time machinist Tom Schmitt and Dean’s fiancé Peru Barber, press on with the engine building business today.

Our “Build”

In speaking with Dean about the engines he commonly sees in his shop, he quickly responded “500EFI.” The engine Dean refers to is the Mercury Racing 500EFI. This engine is based on componentry very similar to the GMPP 502 crate engine, but with substantial external systems for marine use. Boat manufacturers installed many thousands of these engines into a broad spectrum of performance boats, in single, twin and even triple-engine configurations. The 500EFI was superceded by the very similar but more-evolved 525 and now the 565. The 500EFI and its brethren are the engines people look for when used boat shopping and no doubt a common sight in builder’s shop across the country.

In speaking with Dean about his philosophy, he told me his approach is to return the engine to the customer with increased reliability over stock and a few more horsepower on top. The 500EFI being a production engine, the touch of an experienced racing engine builder unlocks both of these.

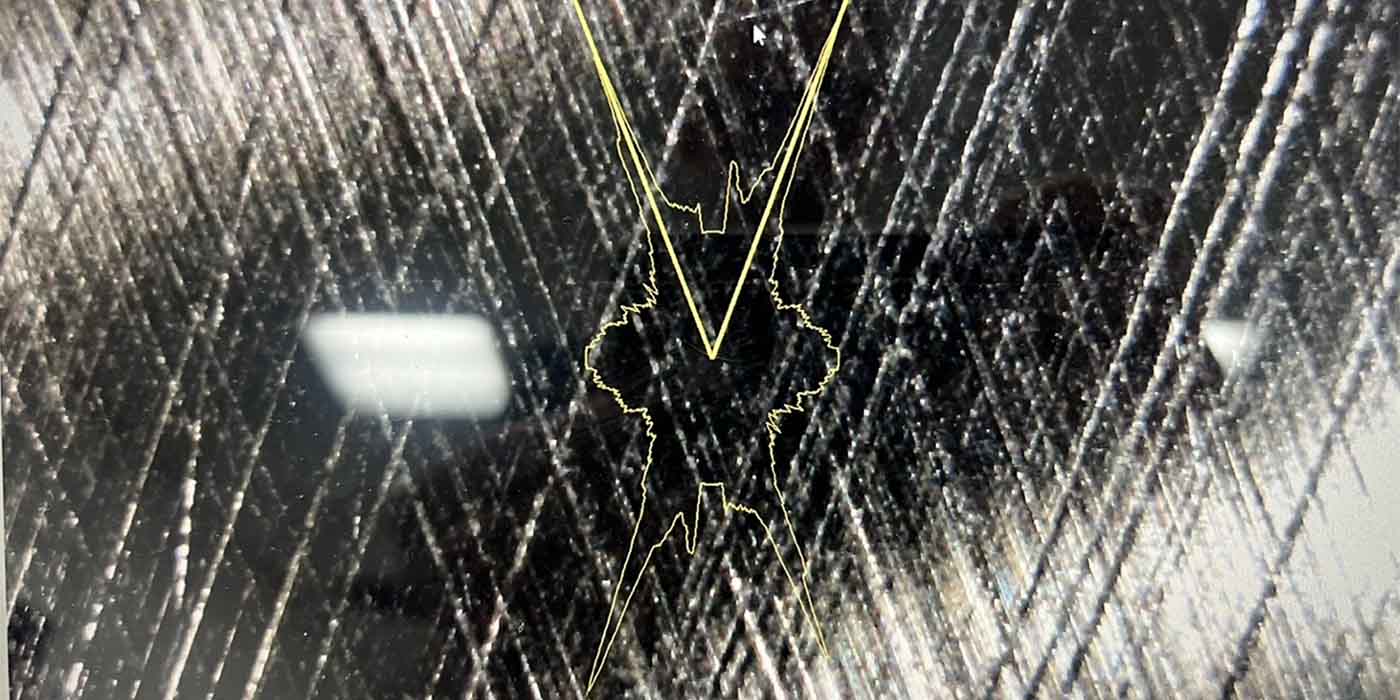

According to Gellner, “Reliability starts on the bottom end. On my basic freshen, I start with crank bore alignment. I don’t recall the last time one didn’t need at least honing – they’re usually tight.” Dean shared that his approach is “more clearance and more oil. I believe in cushion. I open up the mains and rods, and fill that space with oil. My engines usually run in the 70-80psi range hot.”

That approach requires that the replacement high-volume pump he uses be cleaned up and ported as well as shimmed for the additional pressure. Gellner also replaces the stock pan with a higher-capacity aftermarket piece with better baffling, to ensure controlled supply to the pickup.

“I use a 25w-50 non-synthetic oil with high zinc in all my engines” he added. “I also replace the rubber lines to the cooler with larger braided pieces and I typically up the cooler size. Oil is everything in these engines.” Dean also opens up and smooths all the block’s oil passages as well.

During our conversation, Dean shared a thought with me that is some of the best advice I’ve ever heard. “I never let anything go out the door assuming it was done right originally from the factory.” Whether it’s used parts from a disassembled reman job, or parts fresh from the manufacturer, I think every builder would do well to remember those words. Admittedly, they took me back to some mistakes of my own.

Back to the build, Gellner offers that, like line hone, virtually all blocks will need to be decked. “I like to leave the piston about .010” in the hole,” he says. “These aren’t max-performance engines and I don’t want to see my customer needing a replacement block at the next refresh. I like to bring the compression up about a point while I’m in there. It’s free horsepower. These engines were pretty conservative from the factory.”

On cam selection: These engines were fit with a one-size-fits-all cam. “Some boats are heavier and need more midrange; lighter boats, especially cats, need the top-end,” he says. “Even though they might be slight differences, I cam to the application.”

Just as with compression, these engines are conservative on the rev limiter as well. “With good oiling, proper clearances and proper attention in assembly, these engines can spin a bit higher.”

Finishing up on the bottom end, Gellner says he likes to leave “an extra thousandth or so” on piston-to-bore clearance. “It gives the owner some more margin in case they get the engine a little too hot, which happens.”

Some of the best power gains in the 500HP are found with the cylinder heads. While an easy option is to swap the stock units for an aftermarket aluminum head, that can be a budget buster for a customer. Especially considering that with many applications we are talking about two of everything. “I guide line every head. The bronze lubricates the valve stems so much better than the steel guide,” says Dean. “Every one gets a 5-angle valve job with back cut valves. Stainless on the intake and Inconel on the exhaust,” which replace the stock steel pieces. “For a few extra dollars, relatively, I can bowl port the heads, gasket match and port-match the manifold, and give the customer 50-60 horsepower. It’s 30 horsepower less than aftermarket aluminum, but it’s well more than a thousand dollars less.” For a builder like Gellner with a full-time head porter on staff, these services add value for the customer and generate revenue for the shop.

As I discussed with Dean all the various “small things” that go into one of his builds, he added, “We do as needs done. All pushrods get replaced with one-piece chrome moly, but the rockers are as-needed. We clean and flow the injectors. Nothing leaves unless we know it’s good to go.”

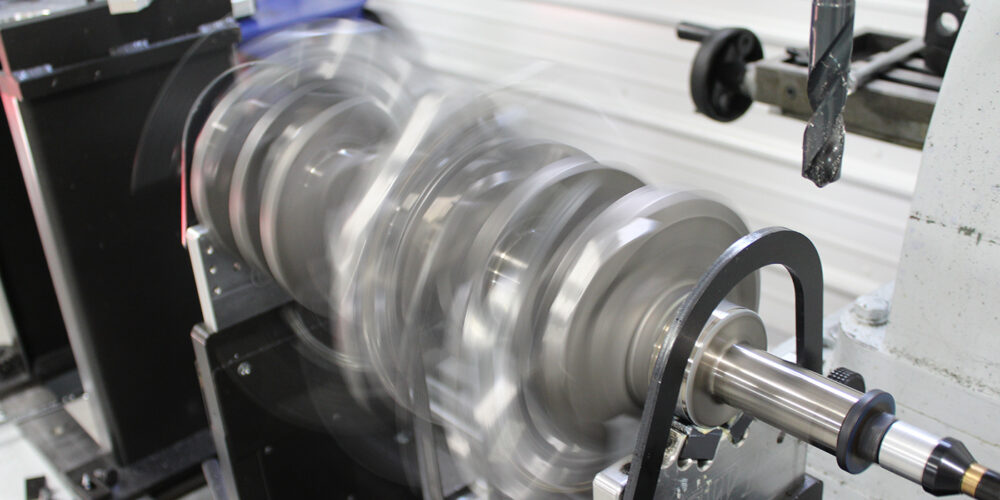

Nothing leaves Dean’s shop without a visit to the dyno too. “We don’t dyno test, we do dyno proofing. Our dyno session is four to six hours. A warmup and three pulls tells you nothing.” Dean is adamant about what he does during his dyno sessions. “First off, Mercury’s tune is way too rich for break-in. We take a bunch of fuel out until everything is settled in. Then we begin work on the fuel curve.” Dean also shared a few dyno room stories, including one where oil steadily dripped out of a visibly-good oil pan weld. “I build these engines to be run hard. My customers come to me expecting that they’ll run hard. I run them hard on the dyno to prove to them that they’ll run hard in their boat. And if it’s going to blow up, its going to do it here.”

Gellner calls this step, “pre-tune.” He does final tuning in the boat with the customer. Dean does not do rigging, but he has a handful of people he deals with to handle that end. This also gives him the opportunity to look over the rest of the boat’s rigging to ensure it is capable of supplying the critical support in the areas of cooling water and fuel supply. “I only take an engine if it’s fully rigged, and the customer gets it back ready to drop in.” By fully-rigged, that means all the plumbing, coolers and electrical system pieces. This ensures that he delivers the maximum the engines are capable of, and also protects him in the event of an issue. After a half-day on the dyno and an afternoon on the water, it allows Gellner to firmly stand behind the work that he does. The in-water test is also a very important validation step. It not only definitively proves to the customer that he got what he paid for and that all is in order, you get to be present when he has discovered that you’ve exceeded his expectations. “Everyone wants to go faster. Virtually all boat owners know how hard and expensive that is to do. When you deliver a boat that out-performs even their best recollections, it truly solidifies your relationship with that customer.”

Gellner went on to share a story of a phone call he received just recently, on a late summer Saturday afternoon. It was a customer calling him from one of his favorite waterfront stops. “I just wanted to tell you that I love this boat and can’t believe how strong it runs, and thank you.” Dean admits that there might have been a few cocktails involved, but that it’s great to get feedback like that from your customers.

When asked, Gellner shared that the average ticket for a refresh such as the one we highlighted is in the $8,000-$9,000 range. While this is on the low end of the work that passes through Dean’s shop, compared to monsters that typically adorn the stands in his assembly room, a handful of these jobs passing through a builder’s shop are guaranteed to move the needle on the bottom line. ν