As a kid, Dan Keenan loved fixing things, tearing things apart, and figuring out a way to build something new. But he never dreamed his skills would one day lead to being a key player in designing a brand-new race engine for NASCAR.

After earning a mechanical engineering degree from Montana State University, he started working on dynamometers. His expertise got the attention of NASCAR race teams, and in 2000, he joined the team at Robert Yates Racing, which would later become Roush Yates Engines (RYE). In 2007, Roush Yates Engines’ President and CEO, Doug Yates, asked him to team with Ford Performance to spearhead the design of Ford’s first purpose-built, made-from-scratch NASCAR race engine, the Ford FR9.

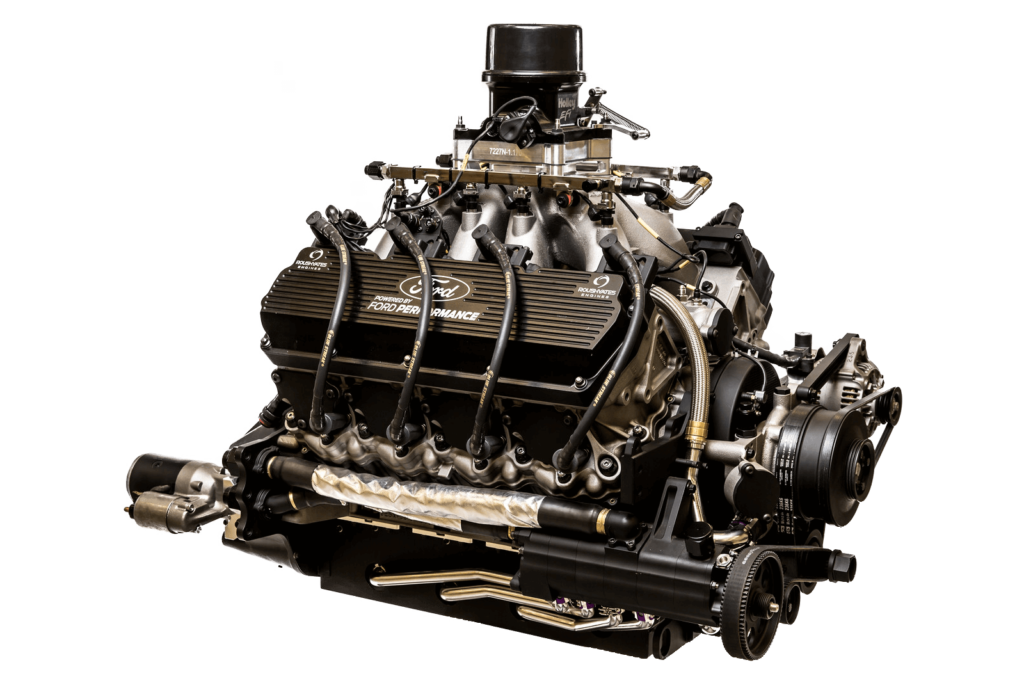

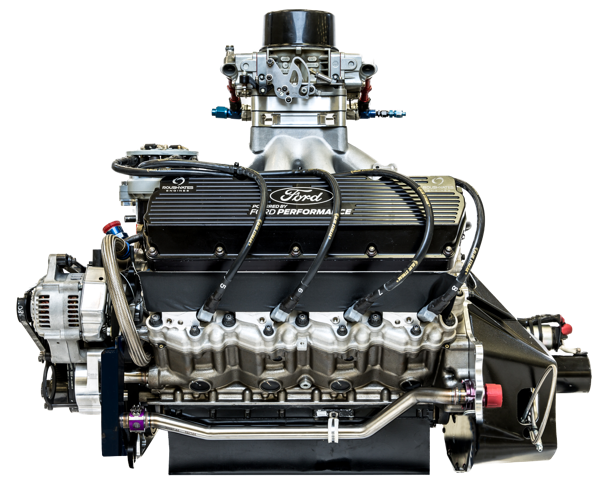

Today, Keenan is the design and analysis manager at RYE. The Ford FR9 is a reliable fuel-injected engine and the exclusive engine for Ford’s Monster Energy NASCAR Cup Series teams. Introduced into NASCAR Cup racing in 2012, the engine design was based off the Ford FR9 carbureted platform, which entered NASCAR in 2009.

As part of the Ford FR9 engine program, these engines are leased to seven teams and 13 drivers, and new engines are delivered for every race. This unique and fast-paced approach allows for delivering the latest in cutting edge technology for each race.

The process of designing and building the FR9 took some time. The plan was to start from scratch, with a clean sheet of paper, and build a motor from the ground up, according to Keenan.

“We had been racing what was called the R452, which was the original block and architecture that Ford had done back in the 1960s,” Keenan says. “That’s what Robert (Yates) did, that’s what Doug (Yates) did, that’s what Jack (Roush) did. They all worked on that.”

The R452 won a lot of races over the years. It first made its mark with what’s commonly known as the “Yates head.” Officially called the C3, this innovative new component, designed by Robert Yates, created such a giant leap in power – more than 50 hp – that NASCAR considered outlawing it. Ultimately, officials told Robert his cars could keep running it, if they made the technology available to other teams, as well. And so they did.

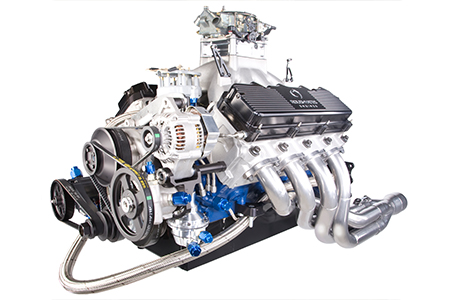

But a lot of new technology was born in the 30-plus years since Ford introduced a new engine. So when Chevrolet and Toyota introduced new powerplants, Ford knew it would take something new and improved to keep up.

“This design would be Ford’s first-ever purpose-built race engine for NASCAR,” Yates says. “But we had not designed a new race engine, and neither had anyone at Ford at the time. So, we decided to collaborate. Our internal design team worked hand-in-hand with Ford’s design team.”

A key challenge for the Ford FR9 engine was being better than the very successful engine it would replace, the D3 R452 V8.

Ford sent Dave Simon, Ford Performance Motorsports Powertrain Supervisor, to North Carolina, where he spent the next several years working closely with Keenan and his team, developing the engine program and a strong partnership along the way. Job one was figuring out the primary goals for the new engine.

“The first thing I did was went around the shop and essentially interviewed all of our guys,” Keenan says. “I went to our builders and said, ‘What don’t you like about the current engine?’ I asked every group what they liked and didn’t like, and unmasked the good, bad, and ugly of our current engines. So we had design goals for the new engines.”

NASCAR, of course, was involved as well, providing specifications and guidelines that must be met for the engine to be approved. Starting at the top of the engine and working their way down, the team added parts. The more they added, the harder it got.

“Once you decide something, your design freedom gets a little bit smaller,” Keenan says. “You decide where your valve lifters are going to be, your freedom gets smaller. You decide what your valve angles are going to be and you lose a little freedom. So we prioritized what was the most important for power and those were the things we were going to have the most design freedom with. Then, as we got down the list, things got tighter and tighter and tighter until we had our engine model laid out.”

From there, the team started printing out parts and bolting them onto a mockup of the new engine.

“We built an entire SLA engine while the block was in tooling,” Keenan says. “Instead of sitting around waiting for parts to show up, we leveraged our in-house 3D System printer and printed basically every piece.”

Meanwhile, as additional time, attention, and resources were poured into the new engine design, nothing else at RYE slowed down. Races still took place every weekend and dozens of new engines needed to be built every week, and the R452 was still winning. In fact, Carl Edwards, driving the #99 Ford for Roush Fenway, finished the 2008 Cup season with a series-high nine race wins. That would be the last year of the R452 engine.

When the day finally came to fire up the first Ford FR9 engine, a crowd gathered around the dynamometer.

“I don’t know what we expected, like streamers to fall from the ceiling or something,” Simon says. “The guys hit the button, it fired right up. Of course it did, we had worked so hard on it. And then we all kind of looked at each other, ‘All right, it idles!’ and then we all went back to work. But it was a pretty fun moment to hear it fire up for the first time.”

Eventually, Doug made the call to stop developing the R452 and focus exclusively on optimizing the FR9. Trying to develop two engines at once was slowing things down, and he knew the FR9 wouldn’t be fully ready until some real pressure was applied.

As always, Roush Yates Engines relied on important partner relationships to overcome key challenges and keep improving the engine. For instance, the team worked closely with Rottler to hone the blocks and long-time partner Cometic Gasket to design and develop a new head gasket system.

“Cometic really delivered,” says RYE Vice President of Sales, Jeff Clark. “They sent people in, they looked at what we were doing on the surface areas of the block, the cylinder head, the deck areas, the clamping that was going to be used, and the different bolts and fasteners, because this was a totally new design. They brought back a few samples that were just incredible, in a very short period of time. Their first attempt at the new design was spot-on, and they continue to deliver all the time.”

Once you have a real, working engine that runs, sophisticated testing is key to making it run better, longer, and faster. Though there’s no real substitute for rigorous on-track testing, RYE used computer simulations to narrow down the number of components needed at the track.

“Doug embraces technology and maximizes it to make our engines more durable, more powerful and to help us understand when we make a change and get a horsepower increase, why it happened,” Clark says. “The success rate is much higher because you’re able to eliminate a lot of bad options before they make it to the track.”

Another key to this process for RYE is their partnership with Convergent Science, which provides Computational Fluid Dynamic programs to simulate the flow of fluids through the engine.

“They provide tools that help us simulate what the engine does without having to actually make parts, do dynamometer testing, and find out whether it works or not,” says RYE Technical Director Jamie McNaughton. “By incorporating some of these engineering simulation tools in CONVERGE, it really speeds up our time from the drawing board to the track.”

One high priority for the Ford FR9 engines was building a superior cooling system, one that would allow the engine to produce maximum power at higher operating temperatures. This lets teams run with more tape on the grill, diverting more airflow to create downforce. More downforce translates to better grip and higher speeds in the turns. It also helps at the two restrictor-plate superspeedways, Daytona and Talladega, where cooling airflow is often compromised by long stretches of running nose-to-tail.

Today, RYE builds more than 1,000 high-performance race engines every year for roughly 128 events around the world. Each FR9 engine, as just one example, has more than 600 parts that need to be inventoried, tracked, and analyzed as efficiently as possible.

Doug’s, Robert’s, and Jack’s vision for the infrastructure, the facility, repeatable processes, and having the very best people in every position provided the building blocks that set the company up for success with the Ford FR9 project.

All said and done, the Ford FR9 EFI V8 has a bore of 4.18˝, a stroke of 3.26˝, a 12.0:1 compression ratio, and can produce 800 hp. Just listen to this engine roar:

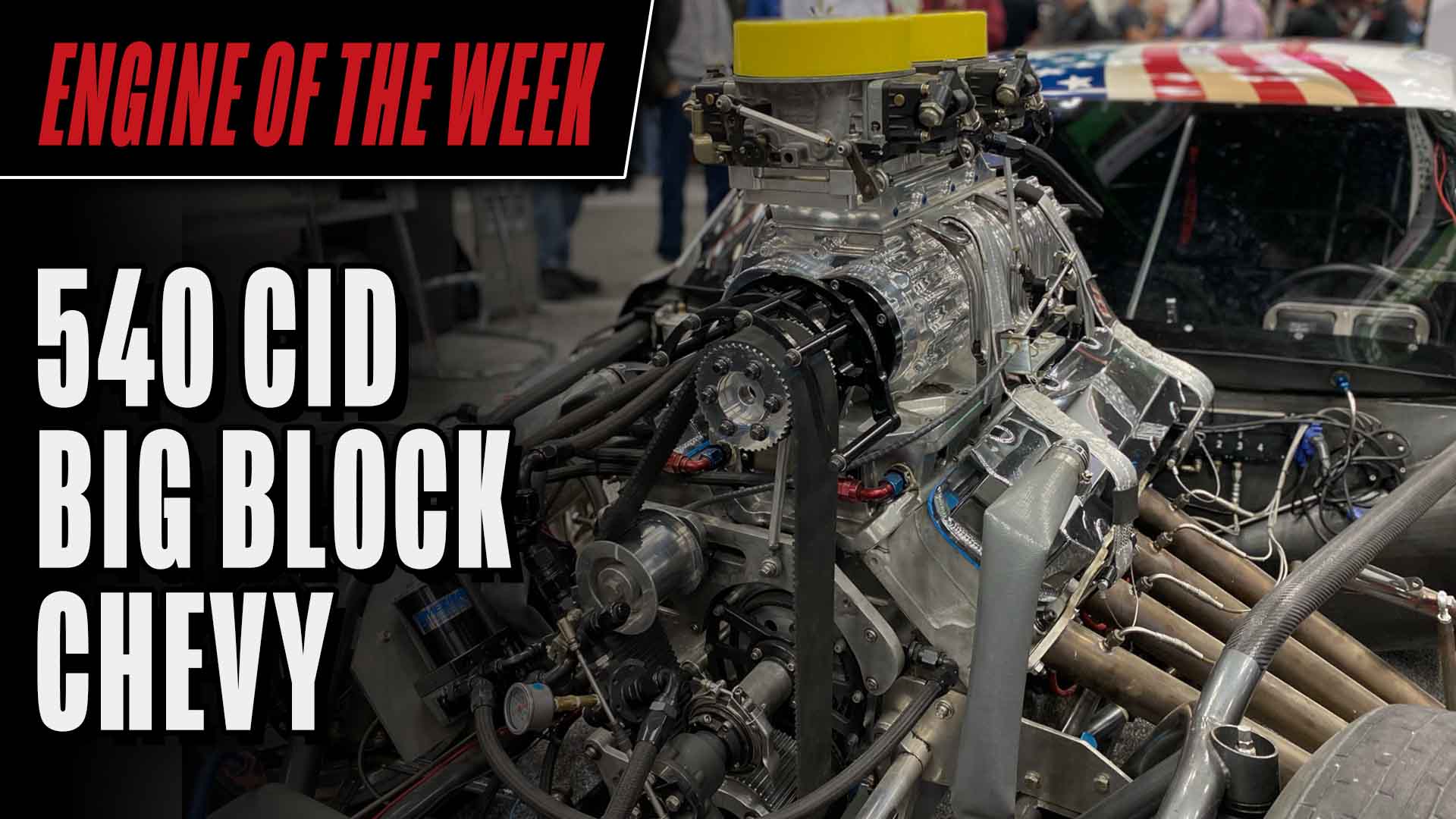

Engine of the Week is sponsored by Cometic Gasket

To see one of your engines highlighted in this special feature and newsletter, please email Engine Builder managing editor, Greg Jones at [email protected]