Burt Munro was born Herbert James Munro on March 25, 1899 in Edendale, New Zealand. From an early age Burt had a need for speed. It started with his father’s horses; he would ride each of them flat out, to see which one was the fastest.

From horses, he graduated to motorcycles. His first motorcycle, a Douglas brand, quickly proved to too slow, so he traded it for a Clyno brand, which also proved to not be fast enough for Munro’s liking.

Then Burt learned about a motorcycle made in America called the Indian Scout, which had the reputation of being the fastest production motorcycle you could buy. In 1920, at age 21, Burt got his Indian. He and the world would never be the same.

The engine in Burt’s motorcycle was a 37 cubic inch (600cc) 42-degree V-twin side valve. This engine design would remain in production through the 1931 model year, and had a reputation of being fast and reliable.

Burt’s Indian Scout had a helical gear primary drive, contained in an oil-tight cast alloy case with a 3-speed hand change gearbox activated by a foot clutch. A double downtube cradle frame, rigid in the rear, was matched with a leaf spring front that gave almost two inches of travel. Final drive was chain. All of these features were pretty modern for the time.

Top speed of Burt’s Indian from the factory was 65 mph, which was considered pretty fast in 1920, when most cars of the era averaged 40-45 mph top speed. Of course, Burt was not satisfied – so in 1926 he began to modify his Indian motorcycle.

One of Burt’s first modifications to the Indian was to convert the engine from side valve to an overhead valve configuration. He started by casting his own engine cylinders. The material he used was cast iron gas pipe that he got when the local utility replaced the old underground gas pipe with new pipe. The old gas pipe was ½˝ thick, and Burt figured the old pipe, which had been in the ground for 40 years, was well-seasoned.

He would heat the gas pipe in sections to burn off the rust, then polish the inside and machine it large enough to install a liner. His cylinder bores got larger and larger, with his largest cylinder bore 3.192˝ x 96mm or 60.54 cubic inches, nearly twice that of the stock engine.

He also made his own flywheels, pistons, cams (which he ground by hand with a file) cam followers, and upgraded lubrication system. He made his connecting rods out of a Caterpillar tractor axle, which he then sent off to become hardened to 143 tensile strength.

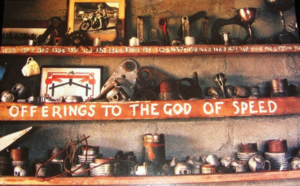

He had plenty of ingenuity, but Burt had little money and no machine shop, only a lathe and a drawer full of hand files and basic hand tools. If he needed a specialty tool he simply made it.

After making new parts Burt would go out on a “speed run” to see what worked and what didn’t. In one month, he went on 17 speed runs and blew up his engine 11 times.

While tearing his engine down he would often find pistons with holes burnt in the tops, piston pins broken in half, cylinders scored and split at the skirt, rocker arms broken in half, along with bent pushrods and bent valves. Burt never gave up, just kept rebuilding and learning from his mistakes.

For carburetors Burt used the Scheblers that came on the newer Indian Scout models, modified to work with his engine. Most of the parts Munro modified came from the same era as his motorcycle, because he understood how they worked and they were easy for him to modify. Burt was willing to try most anything, and once made connecting rods from a melted down DC6 airplane propeller because the 70-70 alloy he wanted to use was not available in New Zealand.

About the only thing Burt didn’t modify on his original Indian motorcycle were the transmission gears themselves. They held up amazingly well. The original transmission part that finally wore out in the 1950s was the sliding dog inside of the transmission – unfortunately, this was no longer available from the Indian Motorcycle Company because the Indian Motorcycle Company had long since gone out of business.

Undeterred, Burt tracked down the company that had bought most of the surplus Indian motorcycle parts when the factory closed. They had what he needed and he was back in business.

Meanwhile, Burt and his motorcycle kept getting faster and faster. After setting numerous speed records in Australia and New Zealand, Burt set his sights on America. He had only one problem – money. How was he going to get there?

In desperation he bartered a ride for himself and his motorcycle on a freighter ship in exchange for serving as the cook. Once he finally got to America he bought an old Nash Station Wagon for $90.00 and headed for the Salt Flats, sleeping in his car and towing his motorcycle behind.

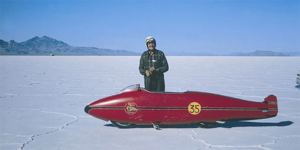

The Bonneville Salt Flats in northwestern Utah is known worldwide for the many miles of flat, compacted salt; perfect for testing speed machines.

Burt would eventually travel to Bonneville 10 times during his lifetime, the first time for “sightseeing” purposes. In the nine times he raced at Bonneville, Burt set three world records: first in 1962, then in 1966 and finally in 1967. He also once qualified at over 200 mph (320 km/h), but because that run was a qualifying run, it was not counted.

- In 1962, he set a 883 cc class record of 288 km/h (178.95 mph) with his engine bored out to 850 cc.

- In 1966, he set a 1000 cc class record of 270.476 km/h (168.07 mph) with his engine bored out to 920 cc.

- In 1967, his engine was bored out to 950 cc and he set an under 1000 cc class record of 295.453 km/h (183.59 mph). To qualify he made a one-way run of 305.89 km/h (190.07 mph), the fastest-ever officially recorded speed on an Indian. The unofficial speed record (officially timed) is 331 km/h (205.67 mph) for a flying mile.

- In 2006, he was inducted into the American Motorcycle Association Hall of Fame.

- In 2014, 36 years after his death, he was retroactively awarded a 1967 record of 296.2593 km/h (184.087 mph) after his son John noticed a calculation error by AMA at that time. That record still stands today!

Burt once said in a magazine interview that he had gained 4 mph every year since 1926 when he first started to modify his Indian Motorcycle.

Burt’s quest for speed and setting records didn’t come without a price. He suffered numerous crashes and broken bones, a failed marriage, thousands of hours of time, and thousands of dollars worth of broken parts.

If you haven’t seen it, track down “The World’s Fastest Indian” on your favorite streaming service or at a video store. It’s a pretty accurate recreation of his life.

Munro spent every dime he ever made on his motorcycle. His goal from the very beginning was to become the worlds fastest Indian. He made it, and even though he died in 1978, his legacy will live on forever.