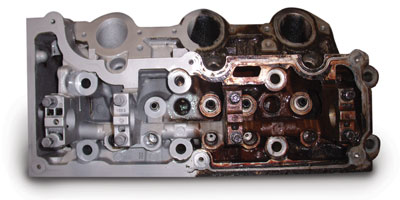

Freshening an engine has always been a game of careful disassembly and evaluating the components for wear followed by a series of judgment calls that balance the cost of new parts against further pushing the veterans. Evaluating pistons takes a practiced eye, but there are several checking points that any engine builder can use to help make the right call.

Here’s what to look for with seasoned pistons.

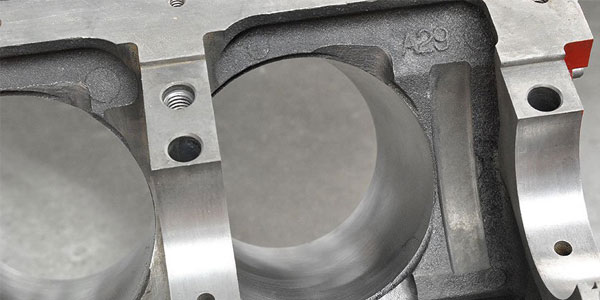

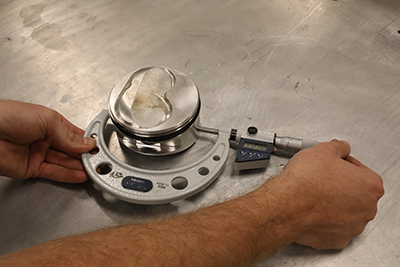

Short of contact damage, normal wear evaluation on a performance piston should start with a quick visual piston skirt check followed by measuring at the piston’s guide point with a micrometer. The guide point is the area on the skirt where the diameter is the largest. On some pistons, this is generally located 0.500″ above the bottom of the skirt, but you should verify this with the piston manufacturer’s individual part number.

If the engine builder recorded the original piston diameter, a simple comparison will reveal any changes. It’s possible to see pistons with partially collapsed skirts from detonation or physical contact problems that otherwise visually check out fine. A minor change in piston-to-wall clearance can be considered normal, but changes in the piston-to-wall clearance of more than 0.002″ should be considered a good excuse for a change.

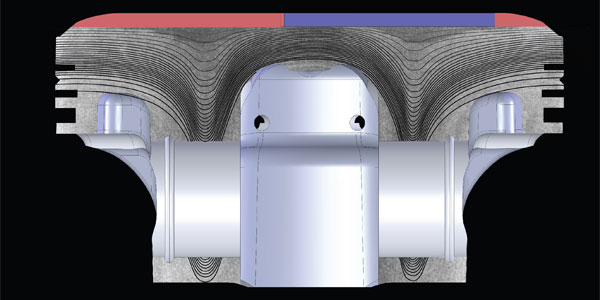

Perhaps the place where wear can cost the most can be found in the top ring groove. All rings use cylinder pressure behind the top ring to increase sealing load on the ring. This demands a somewhat tight axial or vertical clearance between the ring groove and the piston. Although axial clearance recommendations will vary with specific pistons (and manufacturer), a generic clearance of 0.001 to 0.002″ is acceptable. This can be measured with a feeler gauge between the top of the ring and the groove. Worn ring lands can also exhibit more clearance toward the outboard edge of the groove creating a bell mouth effect, which will negatively affect ring seal.

Beyond worn ring grooves, high output engines and especially supercharged or turbocharged engines tend to load the top ring with far more cylinder pressure. Micro-welding is a term used to describe the transfer of small amounts of aluminum from the ring land to the ring surface. This material transfer tends to reduce the axial clearance and may in fact contribute to sticking the ring in the groove. Clues that may point to lost ring seal due to mirco-welding include increased blow-by and lost power.

Piston rings are designed with vertical clearance so that they can freely move within the groove and are induced to move by the angle of the cross-hatch pattern honed into the cylinder wall. Micro-welding can reduce piston ring movement which also contributes to reduced sealing efficiency. When the rings are removed from the piston, evidence of micro-welding will be pitting in the lower surface of the ring groove and the lower horizontal face of the ring itself. This will be more prevalent with pistons that place the top ring closer to the piston crown as this increases the temperature the ring must face.

If either the piston or the top ring exhibit evidence of micro-welding, the only solution is a new set of pistons and rings. Avoiding a re-occurrence of this issue involves careful initial ring break-in that allows establishing early wear patterns that remove the tallest peaks early before maximum cylinder pressure is applied.

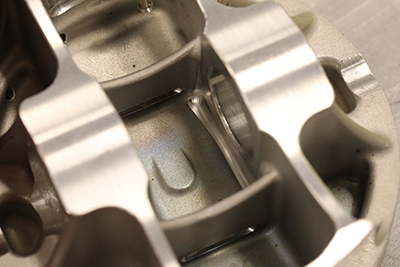

As mentioned earlier, wrist pin and pin bore condition are also areas that should be carefully inspected. If the wrist pin appears distressed through discoloration or it is difficult to remove from either the rod or the piston, that’s a clear indication the pin not only should be replaced but also to use that as a clue pointing toward changes that will minimize that problem in the future. According to many industry experts, if the pin bore is worn more than 0.002″, the piston should be replaced.

Other potential failure points include inspecting the rings to ensure the ring end gaps, especially the top ring, has not butted. If you find the top or even second ring end is highly polished, this is a good sign that the ring end gap was too tight. This may only occur under highly loaded conditions when additional heat expands the ring. But this insufficient ring clearance will immediately bind the ring in the groove, causing excessive wear and the possibility of a broken ring land.

For engines that see extended use at high engine speeds such as endurance or circle track applications, there can be a concern over loss of tensile strength due to heat cycle annealing, or a softening of the original material’s heat treatment. The only way to know for sure is to send the pistons out for a Rockwell or Brinnell hardness test, which can be expensive as it requires a dedicated testing machine.

Careful inspection of the back side of the piston crown is a great indicator of piston condition. If the back side of the piston crown is discolored black, dark purple, blue or any dark color, this is an obvious warning sign that the piston crown has experienced an overheated condition and has likely gone soft. This can lead to eventual failure so swapping out these pistons would be the smart call. This also indicates that perhaps the air-fuel ratio or ignition timing needs to be more closely scrutinized. Conversely, a tan or light brown color on the piston back side is acceptable, usually caused by combustion heat oxidizing a portion of the crankcase oil.

We’ve just hit the most popular places for potential piston distress but piston technicians are always ready to answer questions beyond what we’ve covered here. It doesn’t have to be a game of chance when it comes to piston survival, especially when you can load the positive statistics on your side of the horsepower equation.

This article was sponsored by JE Pistons. For more technical help and insight, visit the JE Pistons Blog!