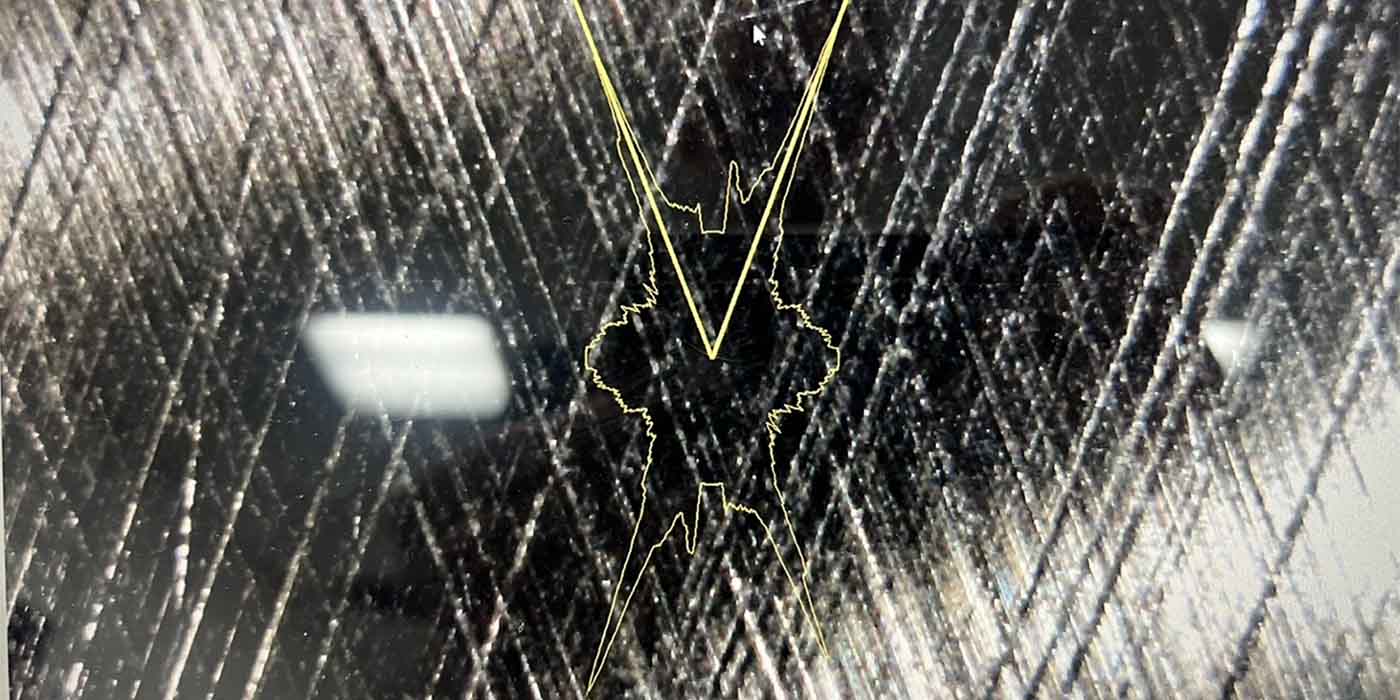

Cylinder head porting is a fairly simple premise – increase airflow into the combustion chamber to make more power. However, making it actually happen requires a bit of work. Improvements to airflow quality and quantity come from porting in the bowl area between the valve seat and valve guide because it is an area of restriction.

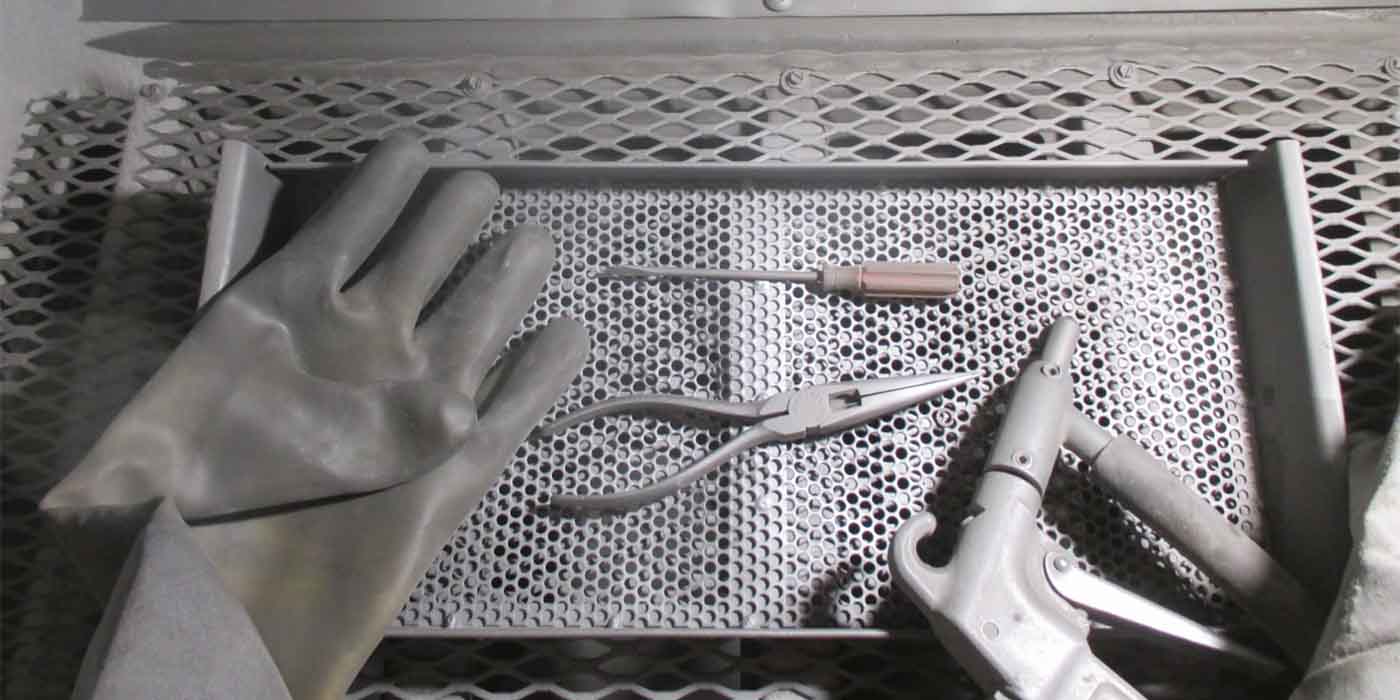

Since every cylinder head is different, learning how to improve airflow characteristics involves a lot of trial and error and many hours on the flow bench to determine if port shape changes have made a difference. The actual act of porting or reshaping the ports generally involves a steady hand and a die grinder with an assortment of cutting, grinding and sanding tools attached. A skilled cylinder head specialist will focus on shaping the port to get the maximum flow with the minimal amount of enlargement so that maximum intake and exhaust air speed is maintained. Specialists are also trying to achieve equal flow through each port so each cylinder experiences a similar air speed.

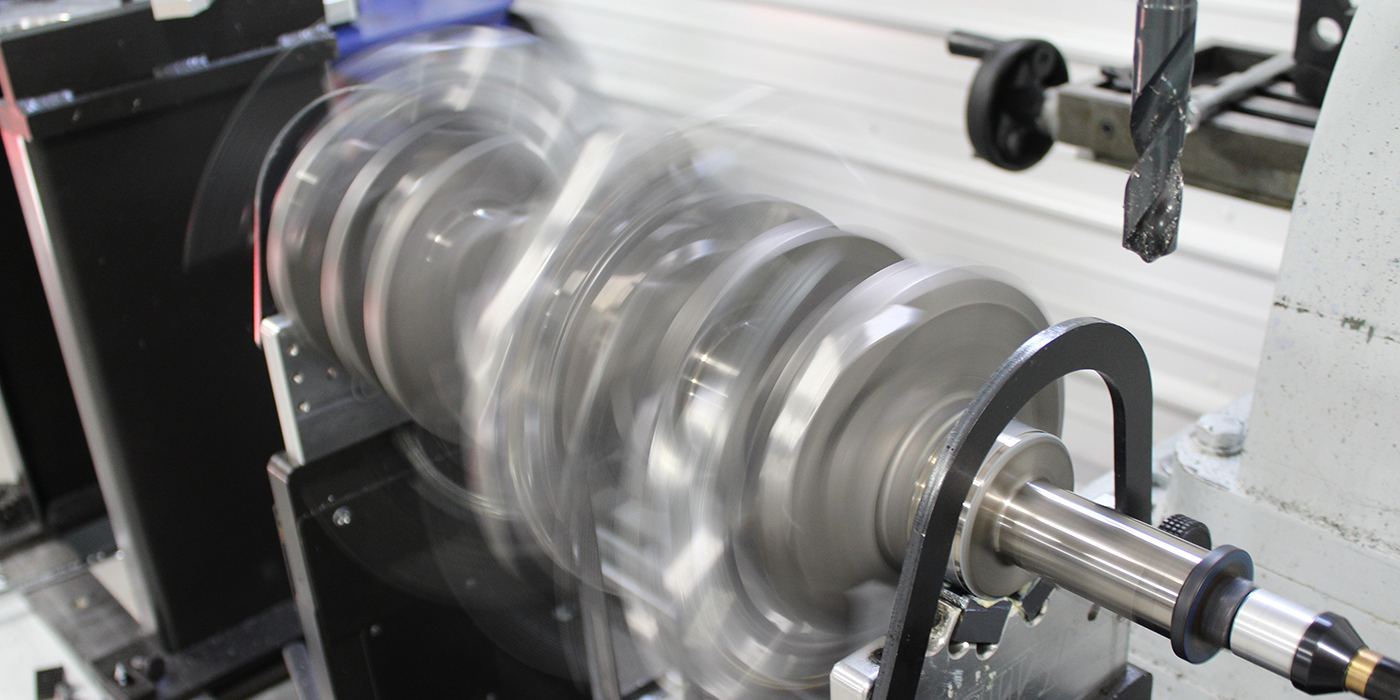

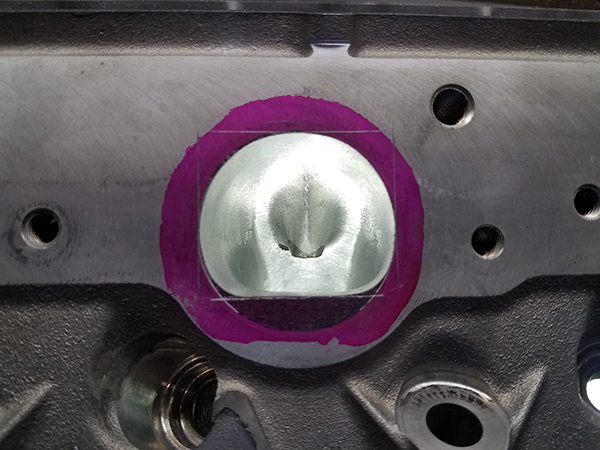

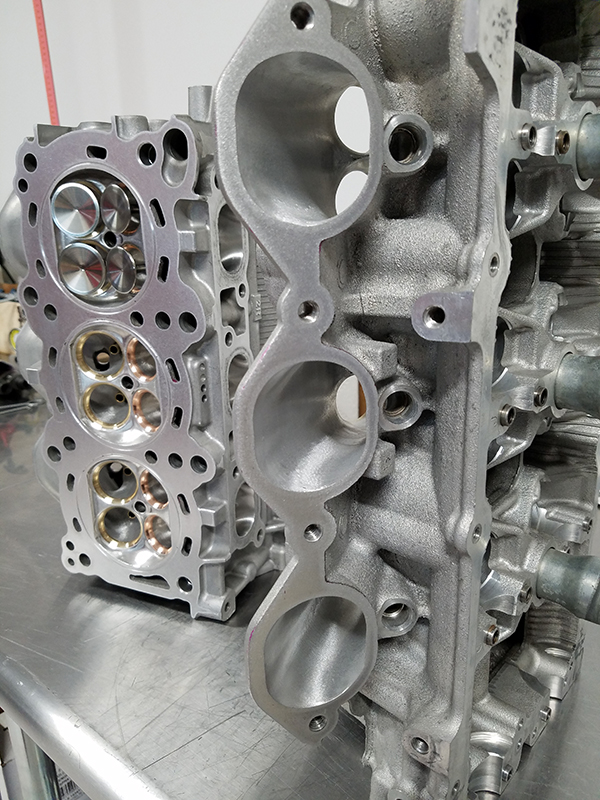

While plenty of folks still hand port cylinder heads these days, CNC porting is becoming a more affordable option. The benefits of the CNC approach are accuracy, repeatability and speed. Once a shop has their CNC program dialed in, they can port heads much quicker than someone at a bench with a die grinder, but whether the result offers anything different from a hand-ported head is up for debate.

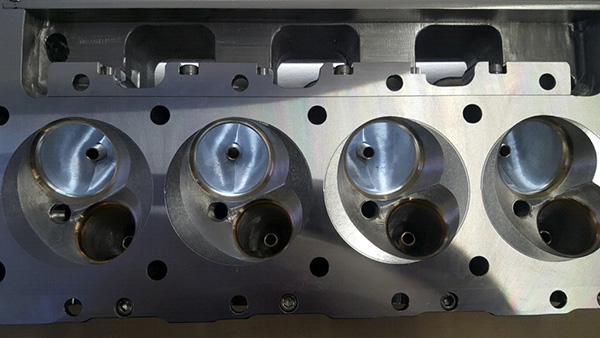

The Value of a Good Valve Job

In general, the most critical areas when porting a cylinder head are those which pass the most air at the highest speed and for the longest duration. Since the highest speed and longest duration airflow happen within the port at or near the valve seat, optimizing airflow in this area is especially important.

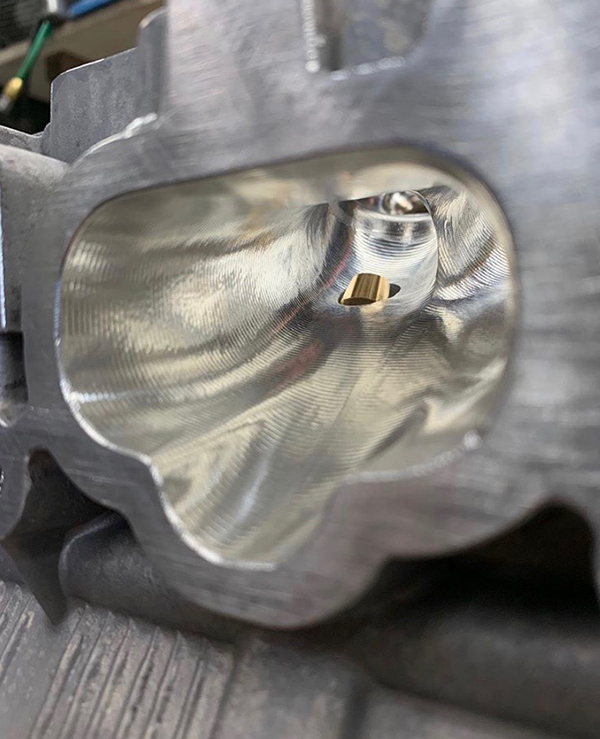

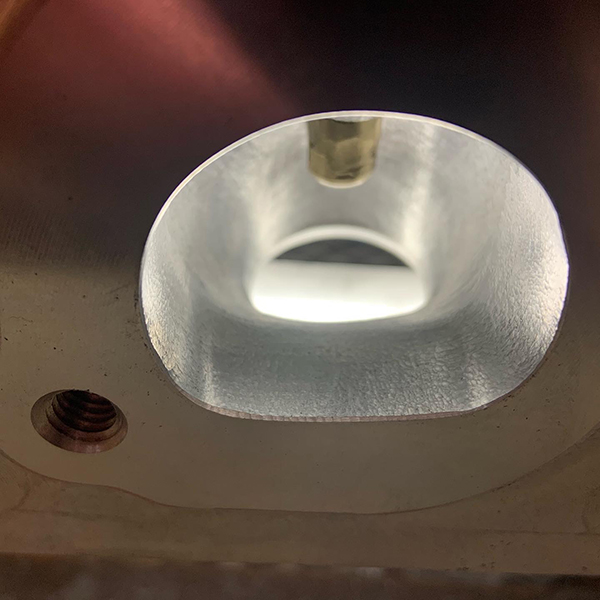

Today, a three-angle valve job is standard procedure, and the first angle cut is the throat cut, which is typically around 60-70 degrees. This helps ease the air’s transition to the seat cut, which is the second cut and is generally done at 45 degrees. This is the surface that the valve actually seals against. The third and final cut is called the top cut, which is normally 20-30 degrees and is made immediately after the seat. This cut helps reduce valve shrouding of the airflow past the valve (or before the valve on the exhaust side) as the valve starts to lift off of the seat.

“A valve job is a very, very, very important part of porting a cylinder head,” says Eric Roycroft, an experienced engine builder and the 2019 winner of the Race Engine Challenge. “The absolute most important part of the cylinder head is from the chamber area on up into the port about 1˝ on each side of the valve. That area, your bowl area, your valve job, your throat diameter and your chamber – those are the absolute most important parts of a cylinder head when you’re porting.

“If you put the wrong valve job on it, you can kill it. What I mean by the wrong valve job is if you use the wrong seat angle and top angle. Your most common is a 45-degree for something like a 15-degree head. As the valve angle changes, you can go to a steeper seat angle. Then, you have a top angle, which blends into the chamber. That needs to blend nice. The bowl transitioning into the throat and into the chamber is a venturi.”

Hand-Porting vs. CNC Porting

Creating that venturi can be done one of two ways – by hand or using a CNC. Some people have always done it by hand and have developed a skill set that is now getting replaced by CNC machines. However, whether you do it by hand or by CNC, you’re still going after the same results. The differences are in repeatability, time and accuracy.

“When talking about the time it takes to hand port a set of cylinder heads versus a CNC, you’re probably talking 10 times the time to hand port a set versus a CNC,” Roycroft says. “You also won’t be as consistent as the CNC machine. You can hand port a cylinder head and get really, really close port by port. They’re not going to be exact. With a CNC, they’d all be the same.

“That said, if you had a port that you hand ported and another that you CNC’d, I don’t know that you would notice a power difference between the two sets of cylinder heads – as long as the person hand porting took their time and the sizing was consistent port to port.”

If you need to make changes to a port using a CNC machine, you can digitally make those changes and run the program. If you need to make changes to a port while hand porting, a lot of times you have to go back and use epoxy in cases where you may have ground a hole or maybe made your short turn too low.

Maximizing Airflow

There’s no question cylinder head porting can be a very effective way to improve the efficiency and airflow capabilities of any cylinder head. But when’s the right time to spend the money? That depends on what you’re trying to achieve with your engine build, but in general, when you upgrade to a bigger turbo or higher lift/duration camshaft and your cylinder head starts to become a bottleneck in the system – it’s time for some head work.

When chasing that last bit of efficiency, factors including the shape, cross section, surface finish and overall volume of the ports come into play. Larger volume ports may seem like a good idea, but more volume can often mean losing torque due to lower air/fuel velocity, especially at lower engine speeds. If taken too far, volume increases can even lead to airflow reversion or backup, where air literally backs out of the combustion chamber towards the intake manifold.

“You can hear it on the flow bench when you have a bad port,” Roycroft says. “It’ll start spitting and sputtering, and what’s happening is the air can’t make the turn to the valve, so the air starts tumbling and flopping around and doing all kinds of weird stuff in the port. That’s usually a result of air speed being way, way too fast.

“If I roughed the port out and the air speed starts backing up at a certain lift number, and I hadn’t gotten to where I want to be in the lift range, I’m going to start probing it and seeing where the port is too fast at. Is it too fast in front of the turn? Is it too fast over on the side of the turn? Is it too fast around the pushrod pinch area? That’s where it comes down to tuning a port up nicely and making it run well.

“Cylinder head porting is something that you develop with repetition. You make subtle changes and you see if it makes it better or made it worse. Air has to pass like a funnel effect. It starts bigger in the front and as you get towards the valve, the port gets smaller and smaller. Ideally, your throat area or your seat ring, would be the smallest spot in the complete port.”

Straightening the ports while increasing volume as little as possible is therefore the most common approach in this area. Combine that with a textured surface on the intake side to encourage fuel atomization and boundary layer activation and you should find most of the remaining airflow gains.

“Some of this stuff is hard to explain,” Roycroft admits. “You’re looking at something you can’t see – you’re looking at air and you’re trying to manipulate how air flows through a port. The biggest thing is to start on the small side and go bigger if you need to. You also want to have nice, smooth transitions. You don’t want any sharp edges.

“I focus mostly on the intake port. The intake port works completely different than the exhaust. With the exhaust port, as long as it’s sized right and you don’t have any weird transitions, you just want to make it as straight as possible. The intake port is completely different.”

Roycroft says he always starts with the valve size. Once he has a valve size that will work with the port and the engine, he works backwards from there.

“You look at your bore size – you don’t want an intake valve right up against the bore,” he says. “If you want to make your intake valve bigger, you’ve got to make sure you’re not going to run into issues, because your port doesn’t stop at the valve. Your port continues on into the chamber, so if you have too big of an intake valve and it’s too close to the side of the cylinder wall, that can hurt you more than it could help you.

“I know about where my throat needs to be once I do the valve job and I know how much area I want up at the pushrod pinch, and then I grind the port out. If this is a new port that I haven’t done before, I’ll rough it out to where I think it needs to be. Then it goes on the flow bench to check air speed and the cfm, etc. I’m mostly looking at the air speed in the port. Air speed, in my opinion, is more important than cfm. If you get a cylinder head that has the appropriate air speed for what you’re doing, the port’s going to flow a lot of air.”

The bowl area, and especially the short turn radius on the port floor, are critical to airflow in most cylinder heads. This is also the area of the head where porting experience comes into play, since changing the radius of the short turn and the overall shapes within the bowl area can have a big impact on the angle the airflow enters the combustion chamber at, which can in turn have a big impact on the combustion event itself.

Common Mistakes

Remember, if you start conservatively with the amount of material you remove, you will avoid a number of potential issues. However, not everyone ends up being conservative, and the last thing you want to do is blast through into a water passage and have to get the head repaired or toss it in the garbage.

“Throat size is something people do incorrectly,” Roycroft says. “Throat size is going to depend on your valve job. Depending on the seat angle and what type of cut angle you use is going to determine how big or how small you can get away with on the throat size. You’re always better to run too small of a throat than too big of one.

“If you get in there and you grind your throat out and you cut all your angles out, you just have a big old hole. Those angles are there on the valve job to help that air turn. If they’re not there anymore, it’s counterintuitive to what you just did when you did the valve job. That’s the single biggest thing I see done wrong. There are so many areas in the cylinder head you can really mess up on, but that’s probably the biggest one is the valve job and the transition into the throat area.”

Conclusion

While you build up your cylinder head porting skills, remember to be conservative. If you can do that, from there, a tool like the flow bench will help you greatly.

“There’s still guys not using a flow bench, and I used to be one,” Roycroft says. “However, since I purchased one and started using it, it’s changed the way I do things and I’m making a little more power than I used to. I can have a port that I think looks good, I can grind it out and think that it will be badass. Then, I put it on the flow bench and it’s like I stubbed my toe – it’s terrible. I never would have known that if I had not stuck it on the flow bench. It’s your equipment to check the air speed in the port. That is the absolute most important aspect of it.”

If you’re looking to gain an advantage on your competition at the track, cylinder head porting should be a high priority. EB