Greg Brown has spent his life honing and crafting top-notch engine building skills, much of it learned during the 13 years he worked for Jon Kaase Racing Engines. It was there that Brown got his first introduction to engine building and dyno competitions.

Recognizing an unmet opportunity in 2018, entrepreneur Greg Finnican stepped up to launch the inaugural Race Engine Challenge, a new engine dyno competition presented by VP Fuels and Lubricants that would encourage engine builders to test themselves and their engines on a dynamometer and under controlled test conditions. Rules were very straightforward and focused on American V8s for the inaugural event and delivered on the motto ‘by engine builders, for engine builders.’

“We knew when we announced the contest that engine builders were excited about the format and the chance to compete on an even playing field,” said Finnican. “There was a lot of discussion on forums and between competitors and fans of previous competitions about what it takes to build a winning engine – we knew it would be really exciting when they were all on site, proving to their fellow engine builders and the rest of the world how good they really are.”

Ultimately, 12 engine builders from across North America made the trip to Charlotte, NC for the dyno racing competition last October.

Having had experience in this kind of competition before as a member of Kaase’s winning dyno racing team, Greg Brown felt confident in his abilities to compete. He launched his own competitive effort in October 2016 after successfully developing a new Hemi cylinder head and founding Hammerhead Performance Engines in Snellville, GA.

“I’m still a one man deal at this point,” Brown says. “I’m doing everything on my own.”

Hammerhead is not a full machine shop, but does have all the necessary equipment for Brown’s cylinder head development and machining. He farms out machine work he can’t do to local machine shops, and he gets dyno time at other shops as well. Brown says despite some limitations, Hammerhead Performance Engines has been a busy shop.

“I have about 17 or 18 engines at the shop at once, which is actually a few more than I really need to have going,” Brown admits. “I do a number of engine types, including big block Chevys and truck pulling engines, but I try to focus on engines that incorporate my heads. I would say 75 percent of the engines I work on are small block Fords with my Hemi heads. The other 25 percent are various engine types.”

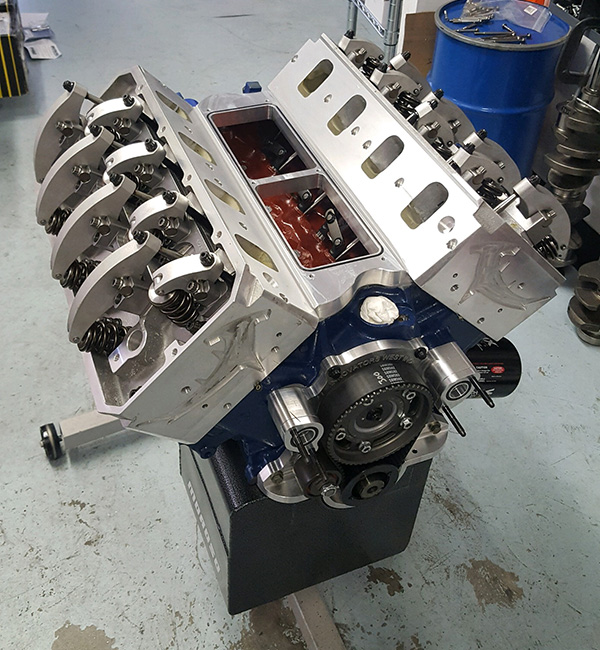

For that reason, Brown knew he was going to build a small block Ford to compete in the Race Engine Challenge, and it would feature his specially designed Hemi heads.

“My idea at the beginning of this process was not necessarily to build a race cylinder head, but to build a good performance head that would be targeted toward the high performance, street car, hot rod market – not necessarily the full race deal,” he says. “However, because I worked in a high end race engine shop, a lot of details about the heads turned out to be pretty racy. Because of the environment I was in and knowing what works and what makes power, the head honestly turned out to be a lot better for making power than I originally intended.

“Obviously, I wanted to use my own product to help showcase what I do. So it was a no brainer to build a 393 cid small block Ford with my Hemi heads on it. My very good friend, Eric Roycroft, also helped me with the engine. The two of us dissected the competition rules and figured out every last little thing that would be an advantage. We then chose our parts.”

One thing Brown understood about the Race Engine Challenge was that the dyno competition would be grading on a power per cubic inch scale. The competitor’s score is a factor that takes into account both horsepower and cubic inch. The bigger the engine, the more horsepower is needed, due to the division of the cubic inch into that number.

“Engines around 400 cubic inches will typically far outnumber any other combination at most competitions,” he says. “I don’t think it’s a coincidence. I think it’s that size engine and the power you can make. It also depends on rpm as well.”

Armed with that knowledge, Brown knew he wanted to keep his small block Ford somewhere around 400 cubic inches.

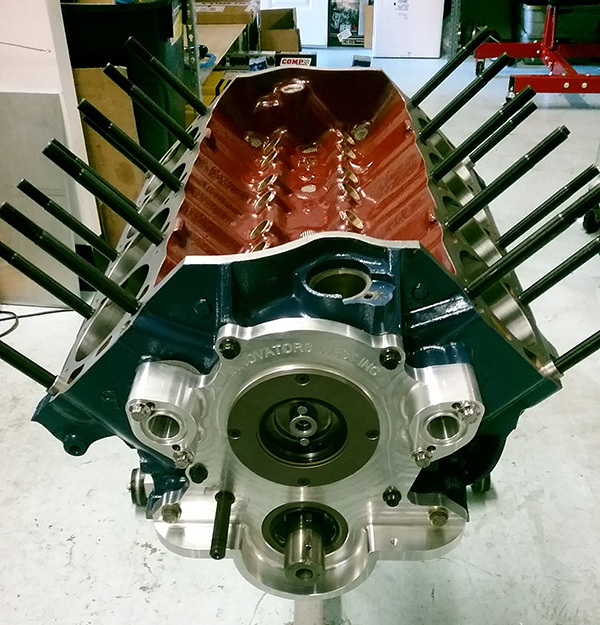

“It was an accident almost that I ran across the crankshaft we ended up using in the engine,” Brown says. “A good customer called me to ask me if I was interested in purchasing this crank. It was just something he had sitting around – it was an NOS (new old stock) forged crank from Ford Motorsport, an odd stroke that they don’t make anymore. It worked out with that crank in my block, the cubic inches ended up at 393. The stroke was 3.900˝ and the bore was 4.004˝.”

Brown says he’s seen people lose dyno competitions by enough points that one cubic inch could have made the difference of winning or losing. He suggests that you don’t really want the engine any bigger than you think it needs to be.

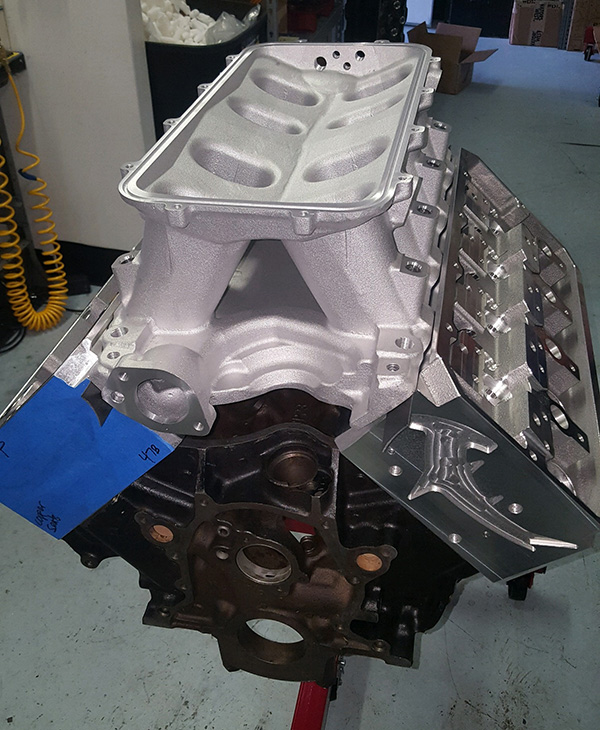

Once Brown had his block and crank set, he turned his attention to the other internal parts of the engine.

“For the Race Engine Challenge, the camshaft rule was no bigger than 55mm journals,” he says. “A regular small block Ford is smaller than that, so we did take the cam tunnel out to 55mm. The lifter size rule was .904˝, so we took the lifters out to the larger size as well.”

Ultimately, Brown built his engine not only to have the best chance of winning the Race Engine Challenge, but to also sell the engine afterward. Therefore, decisions such as the 55mm cam and the .904˝ lifters were made because they’re more enticing to prospective buyers.

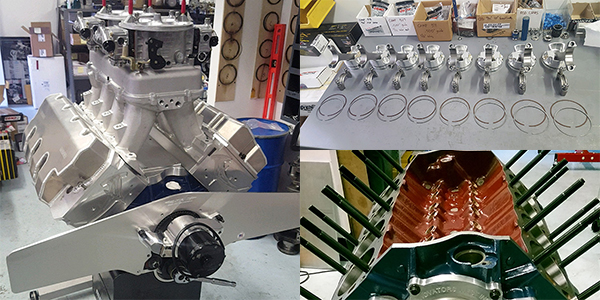

Continuing that mentality, Brown used Diamond pistons on this build and followed the recommended piston-to-wall clearances. Attention to clearances continued through the bearings as well.

“For main bearing clearances and rod clearances, I like .003˝ on both,” he says. “Sometimes it’s hard – even impossible to get there. If you run a coated bearing, you can get by with a little bit tighter clearance. For instance, on the mains where you were shooting for .003˝, if it ended up at .0026˝-.0028˝ it would be fine with a coated bearing. That’s a little bit tight for an uncoated bearing. We always shoot for .003˝ on the mains. The rods are a similar deal. I like to see .0028˝-.003˝. The rods ended up at .0026˝. Because they were coated, we could get by with a tighter clearance there.”

According to Brown, the coolest aspect of the short block is it features a piston guided rod setup. Instead of the big end of the rod keeping the piston straight in the bore, Hammerhead used the piston itself to guide and keep the rod straight on the crank.

“What that means is the small end of the rod will fit somewhat tightly in the piston with only .005˝-.008˝ of side clearance in the pin boss area,” Brown says. “It’s nicer to have a full, round piston because there’s more support if you’re going to use the piston to keep all that stuff straight. The straighter you keep it, the better ring seal you’re going to have and the more power you’re going to make.”

Hammerhead chose a 6.125˝ rod for the 9.200˝ deck Windsor block. With a 9.200˝ deck Brown put a decent stroke in of 3.900˝, and in order to get a good compression height in the piston, he had to go to a shorter than normal rod for the application.

“Normally, I would put a 6.200˝ rod in one of these engines,” he says. “We went back to a 6.125˝ rod but they don’t make that size rod for Ford, so we bought a Chevy rod. We did have to deal with the offset of the Chevy rod when we put it in the Ford engine. When I got them how I wanted in the piston, the rods needed to be machined on the big end so they were sitting on the journal of the crank in the right spot. All the rods ended up having about .005˝-.006˝ machined off of the chamfer side of the big end in order to sit correctly on the crankshaft.”

With the rotating assembly put together, Brown set his sights on designing and constructing the best oil pan for the engine.

“I had Moroso build an oil pan for it at the maximum of the rules, which is depth of the pan and width of the passenger side of the pan for a kick out,” he says. “We put a little bit of a kick out just under the maximum allowed. I built the pan deep to hold a little more oil and to keep the oil as far away from the rotating assembly as possible.”

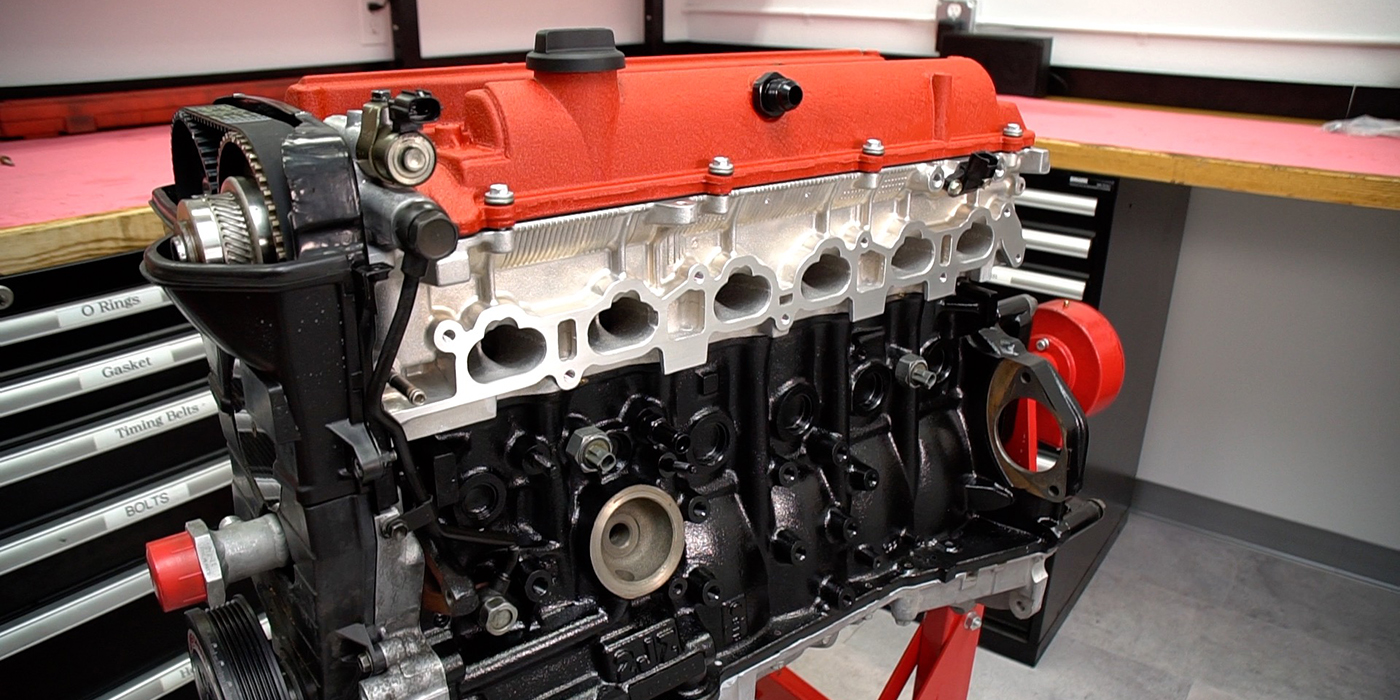

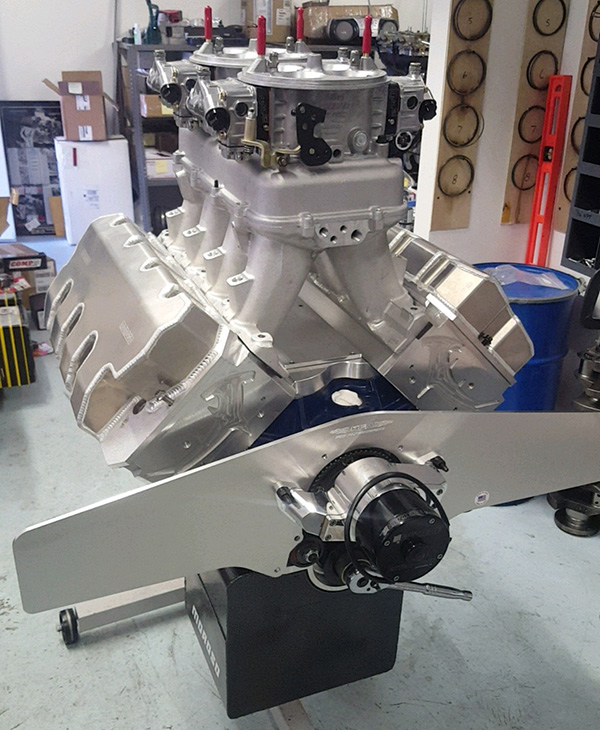

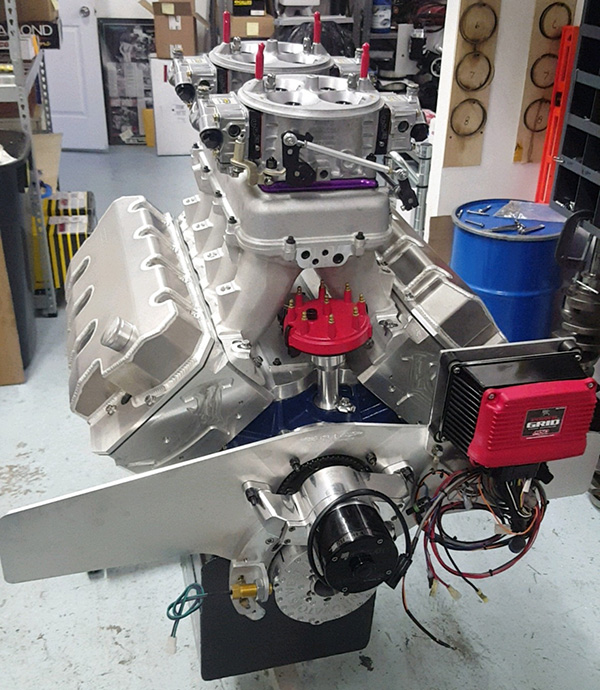

To finish the Hemi cylinder head set up, Brown could use any Windsor 351 intake manifold. However, for that deck height the choices for Windsor intake manifolds are slim. Instead, Brown used a 9.5˝ deck Holley Hi-Ram.

“I did that for two reasons – to keep from having to modify the intake manifold flanges, and because a taller port will make more power and run better,” he says. “We also used two 750 Holley Dominators on top.”

Fully assembled, the small block Ford Hemi engine features a COMP Cams camshaft, Brad Miller double offset .904˝ lifters, an Innovators West belt drive, harmonic balancer and valves, an MSD distributor, Moroso oil pan and plug wires, a Meziere electric water pump, Clevite bearings, a Ford Motorsport crankshaft, Eagle H-beam rods, Diamond pistons, and Total Seal piston rings. It was now ready for competition.

The Race Engine Challenge was split into two classes, an inline valve class and a canted valve/Hemi class. Brown’s engine ran in the latter. The five-day event featured multiple dyno runs per day with the two top engines battling each other on the final day. Each competitor was given the opportunity to make up to 10 dyno runs with the average of their three best runs giving them their score.

“During the qualifying we didn’t change a whole bunch,” Brown says. “We did a little bit of jetting on the carburetors and some cam timing changes. When the qualifying part was over, we were at the top of our group!”

As the leader of the canted valve/Hemi class, Hammerhead went up against the leader in the inline valve class to determine an overall champion. With some help from Dale Cubic at CFM Carburetors, Hammerhead made some major carburetor changes and played with the cam timing once more. Those two things were the difference from qualifying to the final day run off.

“We were able to gain enough points to be better than the other guy’s qualifying runs,” he says. “When the other guy got back on the dyno to try to beat us, he couldn’t match his qualifying number and he ended up being disqualified for having too much compression.”

Fortunately, Brown says he didn’t have any issues with the dyno or the engine during competition. Brown’s peak numbers were 775 horsepower and 622 ft.-lbs. of torque and his average horsepower was 642. Those numbers gave Brown a score of 1,634 and a 50-point lead over the next closest competitor.

“I went there feeling like I had as good, if not the best engine in the contest to win,” Brown says. “It just doesn’t get better than winning a competition, especially winning the first one of its kind! Better than that was winning it with a product I manufacture and sell myself. Having my own product in the competition and winning with it means more than just winning. It was certainly a boost for my business and in the confidence and abilities of my product to perform.”

With his young engine building business taking off, a Race Engine Challenge win under his belt and plenty of engines still to build, Brown says he is looking forward to competing again in 2019. “My plan is to do the competition again, and it should be even better since I learned a decent amount from last year’s competition to make improvements for next year,” he says.