After Adam Cofer bought his first dirt track car in his teens, he quickly realized the car would need an engine – and a lot of parts! He also quickly realized he would need a job to pay for those parts, and what better job to have than working for a local machine shop.

On the grounds of purchasing parts at a discount and trading labor, Cofer landed a job in a local machine shop in Kansas and his interest in racing engines took hold from there. Investing in what would be his future career, Cofer attended the School of Automotive Machinists in Houston and moved to North Carolina after graduating with a goal of getting involved with a professional race engine organization.

Unfortunately, due to the slow economy at the time, Adam ended up coming back to the Kansas area. Despite that set back, his efforts and engine education have paid off. He has spent a majority of his career building and working on 360 and 305 Sprint Car engines.

“In 2017, Salina Engine owner, Tod Roberg, approached me about coming to work for Salina Engine,” Cofer says. “Salina Engine’s focus is on racing engines, with its primary market being Sprint Car engines for various sanctioning bodies. Along with the Sprint Car program, we also do Dirt Modified, Dirt Late Model, Dirt Stock Car, and NHRA Super Class engines. We also build performance street engines for customers.”

Many people familiar with Salina Engine can identify the shop’s work due to its signature look – a painted gray block with black external components. Salina Engine was founded in the 1960s by Russell Roberg as Salina Engine Supply. Throughout the ‘80s ‘90s and 2000s, the business was run by Russell’s children, with his son Tod acting as president of the company.

Salina Engine is capable of doing most machining operations in-house, only outsourcing its CNC cylinder head porting and any necessary cam tunnel or lifter modifications to various outside companies. The shop operates out of a 12,500 sq.-ft. facility that consists of a front office area, parts and storage area, machining area, two assembly rooms, a break room, dyno room, and a tear down area. Keeping Salina Engine running like a well-oiled machine are three machine shop employees, some office staff and owner Tod Roberg.

The shop recently finished up a build on one of its Base ASCS 360 Sprint Car engine packages for a repeat customer who races in the American Sprint Car Series (ASCS). Salina uses a Dart SHP Pro block as the foundation because it is lightweight, has an enlarged camshaft core and .904˝ lifters. It also uses splayed, steel main caps to withstand the rigors of Sprint Car racing.

“Our base ASCS 360 engine build begins with initially ordering our pistons and connecting rods to get a bob weight to order a crankshaft,” Salina Engine says. “Crankshaft availability varies depending upon the time of year, and can be as far out as eight weeks. We also order our fuel injection system at the same time as they are all custom built to our exact specifications, and can be as far out as seven weeks. We chose a Kinsler Fuel Injection Dragon Claw system.”

The first machining operations done in-house are modifying the main housing bore for piston wrist pin oiler jets. After this modification is finished, the shop will brush the mains in its line hone to ensure no burs are present from the oiler modifications. Next, the block gets torque plate honed to a specified clearance to the piston skirts.

“We use our profilometer on each block to maintain proper cylinder finish for ring seal and longevity,” Salina Engine says. “Following the hone we mock up the entire rotating assembly to check for any rotating assembly clearance issues, and to measure the piston deck height prior to surfacing the block. The block is then surfaced to allow for the piston to be a proper height below the bore to achieve our desired quench. All oil passages are checked for proper galley plug engagement, and several other areas are tapped for plugs, including the mechanical fuel pump boss.”

For this particular build’s rotating assembly, Salina Engine used a Callies midweight crankshaft for its cost, weight and durability. All of Salina’s 360 and 410 Sprint Car builds get equipped with Dyers connecting rods, and this engine got Mahle Pro Series pistons and Total Seal rings.

“For our injection manifold we chose to drill and tap two 10-24 threads on the block common wall to attach our injections center valley plate,” the shop says. “We final clean our block and prep the cylinders with Total Seal quick seat and Total Seal assembly lube.”

The crankshaft balance is checked in-house after rough balancing is performed by the manufacturer. Following balancing, the shop will check the rod and main bearing clearance. This particular combination uses 2.448˝ main journals, and 2.00˝ rod journals.

“On every build we verify bearing clearance, and have a range we consider to be acceptable,” Cofer says. “Our ring end gaps are file fit, and being that these combinations run on methanol, we tend to skew toward the lower side of the tolerance on clearance to attempt to further reduce blow by.”

Salina Engine typically uses King rod and main bearings. For its Sprint Car builds, the shop uses the XP series bearings for durability and because they are closer to the clearance spec needed with a standard bearing.

Once all the rotating assembly tolerances are checked, the shop will assemble the short block and degree the camshaft. Camshaft duration and timing will vary depending on the tracks the customer primarily tends to run, as well as the rest of the engine combination.

“We find that duration figures between 255 and 265 work well for most customers,” Cofer says. “On this build we are using an anchored Idler gear drive, common place on most Sprint Car builds.”

Next, the shop turns its focus to the cylinder heads. The shop has some specific modifications it performs on every ASCS engine to help aid in cooling and water flow. It also verifies the valve guide clearance.

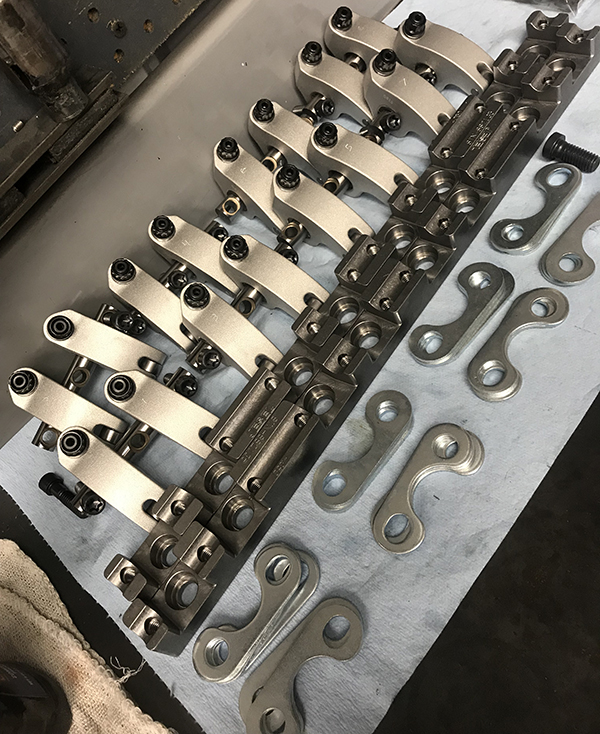

“Typically we are on the high side of what most shops consider acceptable, but have found a bit extra clearance to not cause any noticeable issues, and reduces the likelihood of valve stem galling,” he says. “After these are done, we check concentricity of each valve job. Typically on newly CNC’d heads we have the porting company do the valve job to their specs. Once the cylinder head is clean, we begin setting up our rocker arm geometry for our valve train. We use the stand height setting tools as a baseline, but final height is determined by sweep pattern. We tend to set our valve train up so the rocker stand is in a position to allow the majority of the sweep across the tip to take place early in the lift cycle when spring pressure is lower, and when pressure is higher, the rocker arm is pressing more straight down on the tip of the valve rather than across it.

“With proper geometry set, we check piston-to-dome clearance with clay. Typically, we find on most shelf pistons like this engine uses, that mild material removal is necessary around the spark plug area. We do this by grinding a small portion of the combustion chamber. With dome clearance verified, we begin checking piston-to-valve clearance. Our first step is to verify radial clearance. We allow a minimum of .060˝ on the intake side, and .080˝ on the exhaust side. As for the vertical clearance, we find that similar numbers are acceptable, but typically are able to achieve an acceptable combustion chamber volume without having to run the clearance that close. We find that with these 360 Sprint Car engines we need a minimum of 14.5:1 compression to be at the power level we consider acceptable. Being fueled by methanol, they can tolerate higher, but we seem to find a diminishing return going too far past this mark.”

At this point, Salina Engine will prep the heads for complete assembly. Typically, the shop will run a traditional dual spring with dampener on this application. The base package builds use custom titanium intake valves, and small stem stainless steel exhaust valves. The reduced stem diameter on the exhausts brings their weight down to nearly the same as the titanium intakes. This ensures the valve train will be able to maintain control of the exhaust portion of the system. Prior to putting the springs on, the shop also coats the retainers in cmd paste and puts light oil on the valve locks.

For the valve train on this ASCS 360 Sprint Car engine, Salina used Brodix ASCS Spec cylinder heads, a Jesel Sportsman rocker system, Crower roller lifters, 7/16 .165˝ wall Trend Performance pushrods, Victory 1 Performance valves, and Pac springs, retainers, locators, and keepers.

With the cylinder heads assembled, the shop will put them on to get measurements for pushrod length. This will typically be the last item before taking the engine to the dyno.

“From here we put the front cover on,” Cofer says. “Most Sprint Car applications use a direct drive oil pump from the camshaft and a water pump driven directly off the crankshaft. Because of this, our cover has provisions for mounting both pumps. For our base package we use a three-stage dry sump pump. We have found that the two scavenge stages are adequate to maintain a sufficient volume of oil in the dry sump tank, and help us to reduce the cost of the complete package.”

Salina’s base 360 build uses a Barnes Systems dry sump pump, a KSE timing cover and water pump, plumbing from Earl’s Ultra Pro Hose and Fittings, an Allstar Performance gear drive, and MSD ignition.

With the water pump and oil pump mounted, and the Dan Olson oil pan in place, the shop begins to plumb the cooling and oiling system.

“We use convoluted hose and crimp style hose ends on these builds,” Salina Engine says. “We have a hose crimper and keep an inventory of fittings to be able to do the plumbing start to finish in-house.”

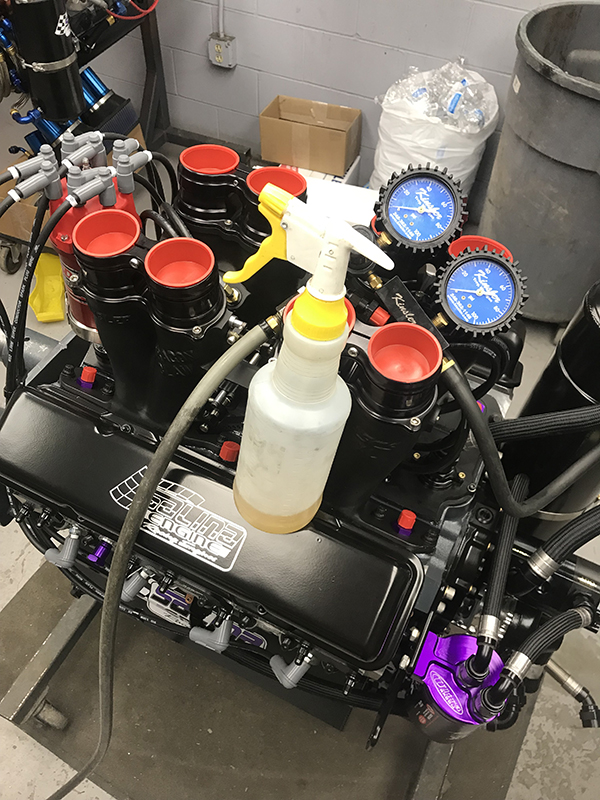

One of the final pieces to go on the ASCS 360 Sprint Car engine is the IR runner manifold. These are very intricate pieces, and require a good deal of attention to detail to perform well on the racetrack.

“The design we use is a three piece with two runners, which bolt to the cylinder heads, and a valley plate which bolts between the runners,” the shop says.

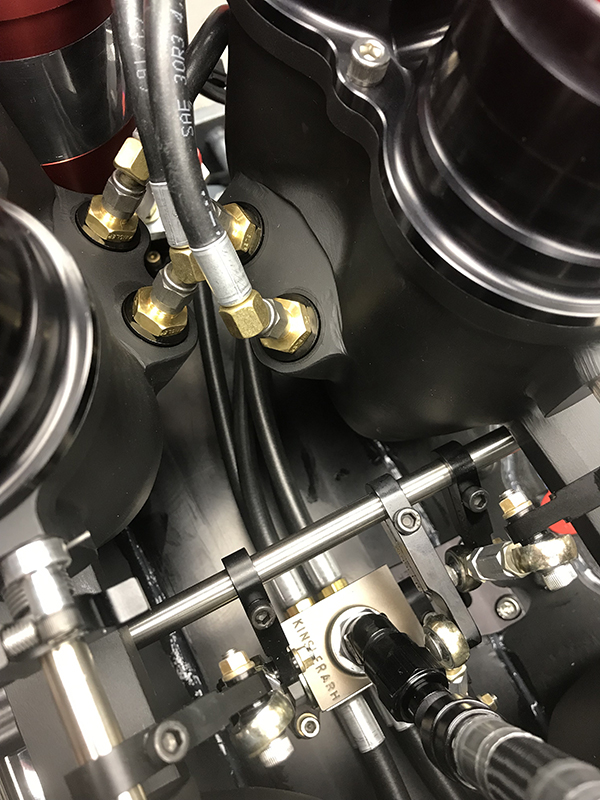

Once the manifold is in place, a good deal of attention is paid to the butterflies and linkage. It is absolutely critical that the butterflies be set to the same clearance on both sides, and that the linkage is timed to open both sides evenly.

“If one side of the manifold is open more at idle, the motor will tend to have a lazy sound, as one side of the motor is over fueled compared to the other,” Cofer says. “Also, if the linkage is opening one side of the manifold faster than the other, it will cause that bank of the motor to accelerate or decelerate at a different pace than the other. Typically this will become evident in starts and restarts as the motor won’t accelerate cleanly. Another sign of unevenness is as the driver lifts the throttle to go into the corner, flames may show from the headers on one side of the motor or the other.”

Along with controlling the butterflies, the IR system is also responsible for maintaining fuel flow to the engine. Sprint Car engines use constant flow injection, which relies on a metered spool known as a barrel valve to deliver appropriate fuel to the engine based upon where the butterfly is in relation to the spool.

“This relationship is set with a leak down gauge,” the shop says. “We find on most engines between 18% and 24% works well. The barrel valve then delivers fuel to the nozzles, which are precision drilled to specific sizes to maintain fuel lbs./hr. to each cylinder.”

With the engine fully assembled, Salina Engine will put 2-4 psi of air pressure to the crankcase and check for leaks with soapy water before priming the engine and hooking it up to the dyno to finish the build.

“One step we always do on Sprint Car engines is to put a sight tube on our oil tank,” Cofer says. “This allows us to ensure the scavenge sections are maintaining oil level in the tank while the engine is running. We have found that some older pumps have difficulty keeping an adequate level of oil within the tank. We also verify our injection side-to-side has been set correctly using an air flow meter pressed into each runner at various throttle positions.”

All said and done, Salina Engine’s Base ASCS 360 Sprint Car engine cranks out more than 700 horsepower and almost 600 ft.-lbs. of torque – enough power to achieve 120+ mph on most tracks!

“The intent of our base package was to attempt to curb the cost of 360 Sprint Car engines,” Cofer says. “Most high end 360s range anywhere from $45,000 to $55,000 for a complete new engine. With our base package, we were able to get this price down to $35,000 and still have a reliable, lightweight and powerful combination.

“We offer packages with price points above this, and for professional race teams, we suggest those higher packages, but this package will compete on most dirt track surfaces right along side the higher priced offerings.”

The Engine of the Week eNewsletter is sponsored by PennGrade Motor Oil and Elring – Das Original.If you have an engine you would like to highlight in this series, please email Engine Builder magazine’s managing editor, Greg Jones at [email protected].