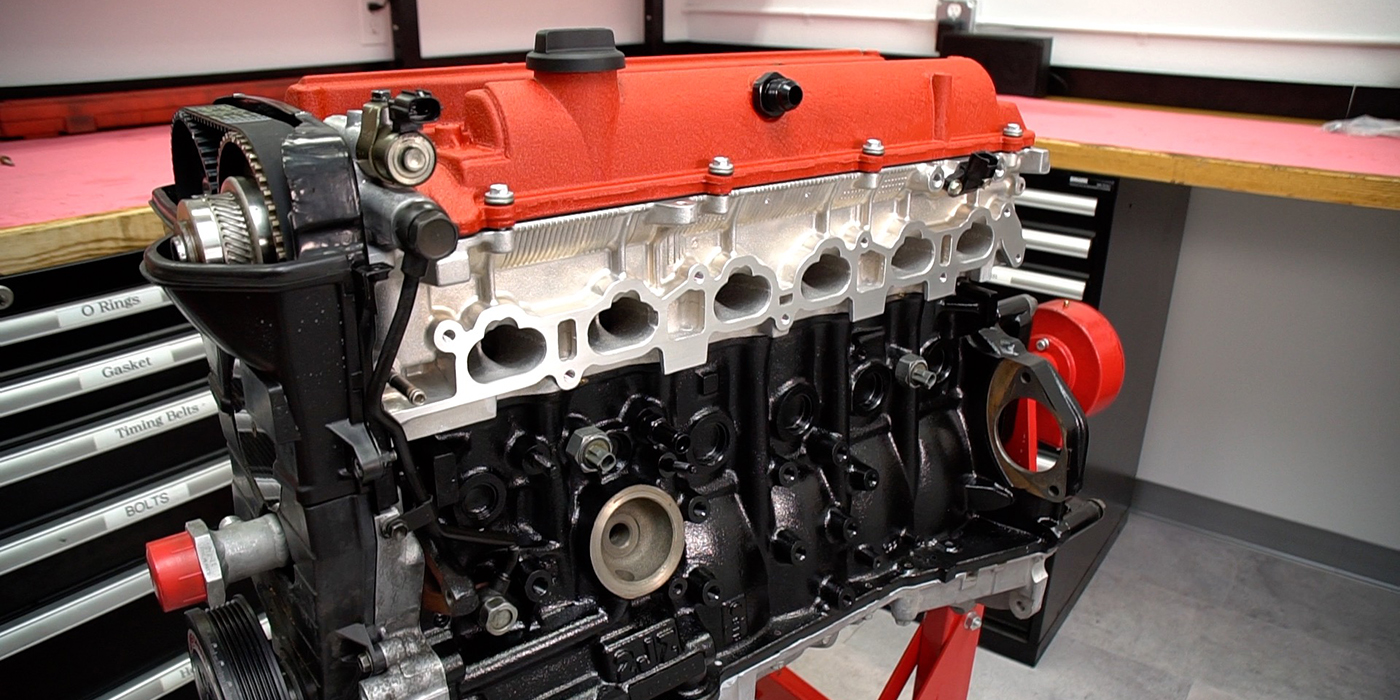

Eric Roycroft’s 370 cid LS3 Engine

“ That wasn’t supposed to happen… this fellow working out of his garage, beat everyone out with an inline engine,” says Race Engine Challenge founder and coordinator Greg Finnican, talking about Eric Roycroft’s unlikely victory at this year’s dyno event. “The big surprise was the engine SAM Tech ran, which was the same engine that won Engine Masters in 2012. One advantage Eric Roycroft had was his cylinder heads had to feed less cubic inches. Since it is a cubic inch divider, having smaller cubic inches is sometimes an advantage as demonstrated there. But it still was a big upset. That was not supposed to happen.

Eric Roycroft showed up to the 2019 Race Engine Challenge (REC) in Charlotte, back in mid-September, with a 370 cid LS3 engine, which he entered into the inline valve class. At the end of the dyno challenge event, which also included a technical conference, Roycroft stood victorious, having beaten the entire inline class, the canted-Hemi class and SAM Tech’s 403 cid SB2 engine, which received runner up.

“I don’t want to say I had it figured out, but I had a pretty good idea about what to do for the engine competition,” Roycroft says. “But it wasn’t easy.”

The reason Roycroft felt so confident was his prior experience, both here at the Race Engine Challenge and at Engine Masters, where he got runner up in 2015 with a big block Chevy. Roycroft had previously helped 2018 Race Engine Challenge winner, Greg Brown, on his engine, having machined both the cylinder heads and the intake. The rules this year were once again enticing to Roycroft, so he threw his hat in the ring.

“The rules package stayed basically the same for this year, and I had a good bit of stuff accumulated already from various projects that I could build what I thought would be a winning engine,” he says. “I didn’t spend as much time on it as I probably needed to, but I happened to throw some stuff together and it seemed to work out pretty good.”

Eric doesn’t own an engine shop, but he works as a shop foreman for a GM dealership. Engine building and drag racing have been his hobby for the better part of 20 years.

“I never could afford to pay anyone to build engines, so I had to figure out how to do that stuff on my own,” he says. “The first engine I built was probably when I was 15 or 16 years old. I don’t know how many I’ve built since then, but I probably build five to 10 engines a year. I do this stuff in my spare time for fun. Some are for myself and some are for customers.”

The 370 cid LS3 was certainly built for himself, and much of the work was done out of Roycroft’s home garage.

“I do everything out of my house,” he says. “I have a small garage that I do all my engine work in. I do all my own cylinder heads and manifolds and I design my own cams. Everything except the block work I do here in-house. I typically use Kaase or Charlie Peppers for all my machine work.”

The Engine

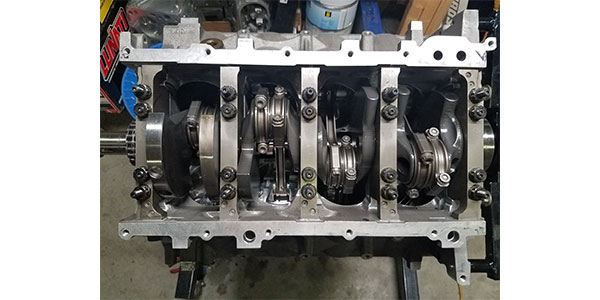

The build started with an LS1-based 5.3L factory block. The rules of the competition have a minimum cubic inch limit of 370 cid.

“I was actually 369.8 cid, but they round up to the next cubic inch,” Roycroft says. “I wanted it to be as close to the minimum as possible. The way I did that was I used a 3.900˝ stroke crankshaft and I bored the block 3.8850˝ to get that cubic inch. That was one of the key things I thought needed to be done.”

When it comes to dyno competitions, one of the most important components on the engine build are the cylinder heads, and Roycroft knew he would need something good. The cylinder heads started as a Liberty LS3 casting, which Eric ported and modified to fit the rules package.

“I spent the majority of my time developing the cylinder heads for what I thought it needed to be,” he says. “Outside of the physical labor of actually porting the heads, the time I took to actually develop an intake port probably took more time than the whole engine build itself. On the heads, I was concerned with the correct airspeed in the port. In my opinion, when you have a port that’s tuned up right and you have the airspeed like it needs to be everywhere in the port, then it’s going to have nice flow numbers. On the other hand, you can make a big port and it will flow a lot of air, but the air is real slow and it won’t run as good. I spent most of my time having the correct airspeed inside the port.”

While dialing in the cylinder heads are critical, Roycroft warns that builders can easily get caught up in finding the perfect airflow and speed numbers, and in most cases, make matters worse by pushing it too far.

“It’s almost an infinite amount of data you have to take in,” Roycroft says. “You’ll get caught up in it. You get to a point where you just have to stop and back up and ask yourself if what you’re doing is really doing anything. You can run in circles pretty easy when you’re doing that stuff. I’ve been doing head work long enough to know where I need to stop. In most cases for me, my first initial port job is usually the best. Anytime I work on it after that, it always gets worse.”

In addition to porting, Roycroft also played with the valve job on the heads, changing the valve job four times until he found something he thought would work the best.

“This engine has such a small bore that it’s really temperamental on what you do with the valve job and how it blends into the chamber,” he says.

The 370 cid LS3 also features a K1 Technologies crankshaft, a set of Lentz connecting rods, custom Diamond pistons, a modified Holley Hi-Ram manifold, ARP hardware, King bearings, two Dale Cubic carburetors, an Innovators West balancer, and a COMP Cams camshaft, pushrods, rocker arms and valve springs.

“In a perfect world, I would have tried things like different headers and camshafts, but I didn’t have the time to do it,” he says. “I took what I learned previously from the engine competition stuff and applied that to a camshaft design that I did. It seemed to work pretty good. It was probably a little too big. If I was to do it again, I’d probably end up with a little bit smaller camshaft.”

When it came to the oiling system, Eric used an OEM replacement oil pump that he ported and modified, and built the oil pan himself from scratch.

With the LS engine finished, Roycroft needed to test it out and make sure there were no bugs. Unfortunately, during a test run the Monday before the competition, Eric hurt the engine and needed emergency machine work done.

“Initially, I had a local guy named Charlie Peppers do all the original machine work for me,” he says. “When I had to repair it, I had Chris at Kaase’s help me out with repairs. If he wasn’t able to stop what he was doing to help, I would have been done.”

While the Race Engine Challenge was nearly a non-starter for Roycroft, he was able to pull the LS engine together and get it to Charlotte on time!

The Competition

On September 16-21, 10 teams of engine builders descended on Charlotte, NC with a goal of running their best of 10 dyno pulls for a chance to be crowned the Race Engine Challenge 2019 champion.

The contest is divided into an inline valve class and canted-Hemi class, and uses a cubic inch divider in scoring to compensate for varied engine displacement. The scored rpm range is 4,000-7,500 rpm with scores determined by averaging three of the best average horsepower dyno pulls out of a possible 10 pulls permitted. The sum of the average corrected horsepower quotient is multiplied by 1,000 and then divided by the claimed cubic inches.

“Because I hurt this engine on the dyno the Monday before, I basically went into the competition with a virgin engine,” Roycroft says. “I didn’t have any data on it. I didn’t tune the carburetors. We basically started from scratch. The engine had not run since I repaired it. I went to Charlotte with an engine that I really wasn’t sure if it was going to hurt itself again or if it was even going to run.

“At the competition, we spent the majority of our time working on the two carburetors. Fortunately, from my first dyno pull to my sixth or seventh pull, I picked up about 80 points on my score, and I probably picked up 60 or 70 horse for peak power. I was around 680-690 peak horsepower from the first pull. The last pull I peaked at 750 horsepower, which is a little over two horsepower per inch. It made over 1.6 per inch torque.”

When the dust settled, Roycroft came out on top as the 2019 champion with a score of 1,658.2. Overall, he says the Race Engine Challenge went really well and the dyno ran great, but that isn’t stopping event coordinator Greg Finnican from resting on his laurels going into the event’s third year in 2020.

The Future of REC

“Next year, we’re going to make a few tweaks to the existing rules,” Finnican says. “We’re also going to add a third class I think will be very popular.”

One big change for next year is rather than an inline valve class and a canted-Hemi class, the 2020 REC will be divided into a Tunnel Ram class and a single plane cast intake manifold class.

“What we’re going to do is instead of having a canted-Hemi class and an inline class, we’re going to have a Tunnel Ram class, regardless if you have an inline or canted-Hemi engine,” Finnican says. “We’re also going to have a single plane cast intake manifold class. You can be fuel injected or carbureted, but it’s got to be a cast single plane intake. The only welding permitted on the exterior is if you put an injector bung in the manifold.”

In addition to the changes in the two main classes, the minimum cubic inch limit will be raised to 400 cid.

“The reason I made it a minimum of 370 cubic inches when we started off last year was not to rule out an LS 6.2L or a late model Hemi,” he says. “I don’t think that’s necessary anymore. Next year, if you’re less cubic inches than 400, you will still be scored as 400 cubic inches, but you can come and play.”

Finnican also plans to introduce an exciting, brand new, third class to the competition called Classic Rivals. The engines eligible for this class will be based on specific brands. Much more on these class changes and new rules will be unveiled by Finnican during the 2019 PRI Show in December.

“The idea with these changes is to have a spot for everyone,” Finnican says.

For now, REC competitors will be gunning to dethrone Eric Roycroft in 2020.

2019 Race Engine Challenge Final Scores

- Eric Roycroft, LS3, Inline, 370 cu in, Peak HP 750, Score 1,658.2

- SAM Tech, SB2, Canted-Hemi, 403 cu in, Peak HP 788, Score 1,651.1

- Randy Malik, Yates SBF, Canted-Hemi, 382 cu in, Peak HP 740, Score 1,599.9

- Greg Brown, Hemi SBF, Canted-Hemi, 412 cu in, Peak HP 820, Score 1,596.4

- Randy Malik, SBC, Inline, 400 cu in, Peak HP 728, Score 1,517.8

- Josh Myers, LS7, Inline, 429 cu in, Peak HP 743, Score 1,478

- David Vizard/Terry Walters, SBC, Inline, 420 cu in, Peak HP 702, Score 1,466.8

- Ben Robey, SBF, Inline, 376 cu in, Peak HP 608, Score 1,389.2

- Tim Davis, BBF, Canted-Hemi, 462 cu in, Peak HP 759, Score 1,370.9

- Darrick Vaseleniuck, SB2, DNF

- Dale Robinson, Olds, DNF