How do you top greatness? With even greater greatness. At least that’s the recipe GM successfully used to create an even better Chevy small-block engine.

The original Chevy small-block has been (and frankly, continues to be) the most popular and successful engine ever created. Introduced in 1955, it wasn’t GM’s first V8 (that honor, according to Motor Trend magazine fell to a little-remembered 1917-1919 Chevy Series D engine) but it was the engine designed to compete with the venerable Ford Flathead. Since its appearance as an option in the 1955 Bel Air and Corvette, it has found a home in a wide range of GM vehicles from sports coupes to full-size trucks, and has been a more-than-suitable replacement engine for imports, other major domestics, hot rods and kit cars and even light aircraft.

The Gen III version of the small-block – which started with the LS1 V8 in the 1997 Corvette – has proved to be a worthy successor to the original. This new engine family had the same bore spacing as the original small block, but that’s the only thing that stayed the same. The Gen III engine was smaller and lighter, it made more horsepower and torque per cubic inch, created fewer emissions and got better fuel mileage than the Chevy 350 it replaced. It was designed to be built in multiple displacements from day one so it could be used in a wide variety of cars and trucks later on.

Shortly after GM introduced the LS1 in the ’97 Corvette, the company created a whole new family of small block truck engines based on the LS1, including the 4.8L, 5.3L, 6.0L and the 6.2L that each came with a number of variations over the years.

GM built nearly 30 different versions of these truck engines during the past 15 years. They all share a common architecture and quite a few common parts, but there are significant differences between the Generation III (Gen III) and Generation IV (Gen IV) engines along with plenty of variations from year to year.

Just to put it all in perspective, there were seven different 5.3L engines in 2005 alone – along with the 4.8L and a couple of 6.0L motors. Sorting them out has been a challenge, but Engine Builder contributor Doug Anderson did just that in a series of detail articles on the engine family. Using cores, some take-out motors and a pile of new parts, he was able to figure out most of the combinations and where they were used – those articles are avaible for reference on the Engine Builder website (www.EngineBuilderMag.com).

The key to cataloging the Gen IV engines is an understanding of the changes that GM made to the Gen III engines to make them more suitable for truck applications. They needed more torque, more power and better fuel economy along with lower emissions, so Chevy modified the block and several other components to accommodate cylinder deactivation (Chevy calls it active fuel management or AFM) and variable valve timing (VVT).

It (and the subsequent next Generation, Gen IV) consists of several different V8s ranging from the 5.3L LS4 to the 7.0L LS7 in domestic automotive configurations and Vortec 4.8L to L92 6.2L truck engines. They have their similarities, they have their differences…but they have enough similarities that they’re all part of the LS engine family.

Engine Builder magazine has surveyed our readers to ask how much you charge for various rebuilding and machining operations. This Labor Costing Study provides a look at national and regional average labor charges. We cover various head, block and crankshaft service procedures as well as miscellaneous labor charges.

The individual charts begin on page 34. In addition, the detailed chart on page 30 represents the national average, median and mode labor charges for all of the procedures covered in our survey.

We break down the individual charts by the four census regions in the U.S., which gives us consistent measurement across the country. In addition, we use a weighted average to determine the national average. Your business operations may allow you to be more efficient than these charts indicate or you may find that your costs are somewhat (or even significantly) higher than others in your same area – nothing wrong with that. Any variations should not automatically be seen as indicating that your costs are either too high or too low. But they will hopefully give you an incentive to look carefully at what you charge for service and why.

The “average” for a specific labor charge is the result of adding all of the charges for that service from all respondents and then dividing that number by the total number of respondents. The “median” is the result of ranking all of the survey responses from highest to lowest and then finding the number that falls exactly in the middle. The “mode” is simply the most-often reported number from all survey respondents.

Additionally, our chart provides the “95% Confidence Interval (CI)” range. In real terms, if you were to ask all of the machine shops in the country what their labor rates were for each operation, it is 95% certain that the “true” average labor cost would fall within this range.

“Some shops may include certain operations in the process of doing others,” explains Kent Camino, Manager of Market Research for Babcox Media. “This may mean they charge more for a ‘complete’ operation. Additionally, some shops may have given us an ‘each’ price when we wanted ‘all’ or they may have included an ‘all’ when we asked ‘price each.’”

Camino says while the overall results remain statistically reliable, the way some respondents answered the question may have skewed certain numbers slightly.

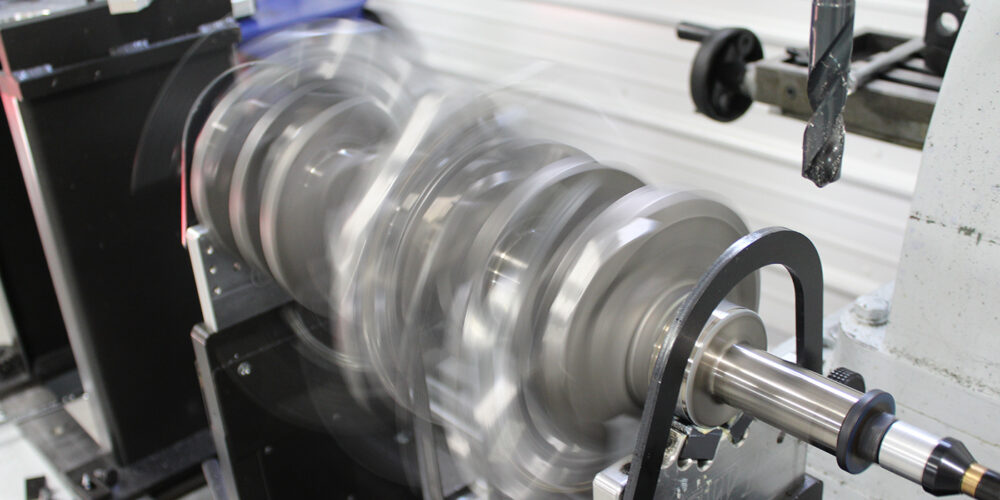

cylinder bores is crucial to high performance engines, experts recommend the use of deck plates when boring and honing the cylinders.

“Some shops reported to us that they perform some repairs on a ‘time’ basis. We did not use a dollar-per-hour value if they provided it. A few shops price all their repairs on a ‘time’ basis. This is most common with welding repairs. Some shops do not perform all the operations listed and this leads to a smaller number of observations and thus a less reliable average,” Camino says. However, he says, “In all cases, the national average will be the most accurate figure.”

Engine Builder magazine has written extensively about the LS engine family, from complete build specifications to technical bulletins related to cylinder head and block procedures to individual component product highlights. You can find all of the information in our exclusive online archives – visit www.enginebuildermag.com and search for LS engines.

You’re probably already working on these Gen III and Gen IV engines, and depending on your specialty you may have already started seeing the Gen IV Chevy small-block on your assembly benches. The next time you find something exciting or unique about one of these builds, would you take some pictures and drop us a line? We’d like to see what you’re up against.

Keep an eye out for the August digital edition of Engine Builder for more information from our Labor Costing Study.