Grassroots racing is the backbone of the performance industry in this country. It’s weekend racing at small town local tracks, drag strips and road courses by average Joes’ who just enjoy racing. They race for glory and peanuts prize money. They don’t have mega-million dollar sponsorships, high paid crew chiefs or engineers, or a PR agent to deal with their fans. They’re not celebrities, household names (except maybe at their own track) or into product endorsements. These are the racers who make up the majority of our reader’s customer base.

In researching this article, we discovered that there are more than 1,200 dirt tracks around the country (most of which are 1/4 mile, 3/8 mile or 1/2 mile tracks), about 120 drag strips (1/8 and 1/4 mile), and a few dozen paved road race courses (excluding off-road courses). Many of the dirt tracks also serve double-duty for truck and tractor pulling events, too.

Rules, Rules, Rules

Rules dictate what is and what isn’t allowed in all types of racing, whether grassroots or professional. Rules are established for a reason. The main purpose (besides safety) is to equalize competition so the rich guys with deep pockets can’t outspend competitors and have an unfair advantage over the other racers in the class.

A dry sump oiling system that’s capable of pulling a strong vacuum in the crankcase can provide a 10 to 15 horsepower advantage over a wet sump system that has a lot of windage and drag in the crankcase. So if the rules only allow wet sump systems, everybody is on the same page more or less as far as crankshaft windage and drag are concerned.

On the other hand, even if the rules restrict everybody to using a wet sump system, there’s a lot of wiggle room as to what type of wet sump system a racer may use. A wet sump system with a well designed scraper in the oil pan can cut crankshaft windage significantly. Building the engine with tighter rod and main bearing clearances and using a lighter viscosity synthetic racing oil also means you can get away with less oil pressure, which means less power consumed to drive the oil pump and more power at the crankshaft. And for endurance racing, adding an external oil cooler and/or oil reservoir can keep oil temperatures within safe limits – which reduces the risk of blowing an engine and not finishing the race at all.

A secondary reason for rules is to limit costs so the “little guys” can afford to compete and to equalize competition. Keeping costs down is a cornerstone of grassroots racing. The sky is the limit as to what a racer can spend on modifications and goodies for his racecar. By putting a lid on what they can modify or what parts are allowed, rules keep racing affordable and competitive (in theory, anyway). Creative individuals can always find ways around the rules by stretching what the rules say (or don’t say), while others simply ignore the rules and find ways to cheat – until they get caught.

So priority one when choosing an oiling system for any type of racing (grassroots or professional) is to establish what the rules allow and prohibit. Somebody has to read the rule book. Whether that’s you or your customer it doesn’t matter. The oiling system has to fit within the framework of the rule book. Period.

To keep costs down, most dirt tracks prohibit dry sump systems in most stock, sportsman, late model and modified classes. A track may have its own rules or may subscribe to the rules of a particular sanctioning body such as the American Motor Racing Association (AMRA), DIRTcar, International Motor Contest Assn. (IMCA), United Midwestern Promoters (UMP), U.S. Auto Club (USAC) or another group or sponsoring organization. With drag racing, most strips follow National Hot Rod Association (NHRA) or International Hot Rod Association (IHRA) rules. For road courses, the sanctioning body may be the Sports Car Club of America (SCCA), National Auto Sport Association (NASA), World Racing League (WRL) or a local car club’s own rules.

As far as lubrication systems go, some rules are rather broad and generalized. Rules that prohibit dry sump systems may allow any type of wet sump system. Other rules may limit wet sump systems to “pure stock” components or “stock appearing” aftermarket parts (which leave some wiggle room for a higher flow oil pump and/or stronger castings).

Some oiling system rules are extremely specific. These rules only allow certain OEM part numbers to be used (with no or limited internal modifications to oil pumps and pans). Or, these rules may allow only certain aftermarket parts to be used. SCCA rules are VERY specific about this in many classes, listing specific brands and part numbers of aftermarket parts that are allowed. The SCCA rule book is a hefty 942 pages – more than double the 324 pages in the NHRA drag racing rule book.

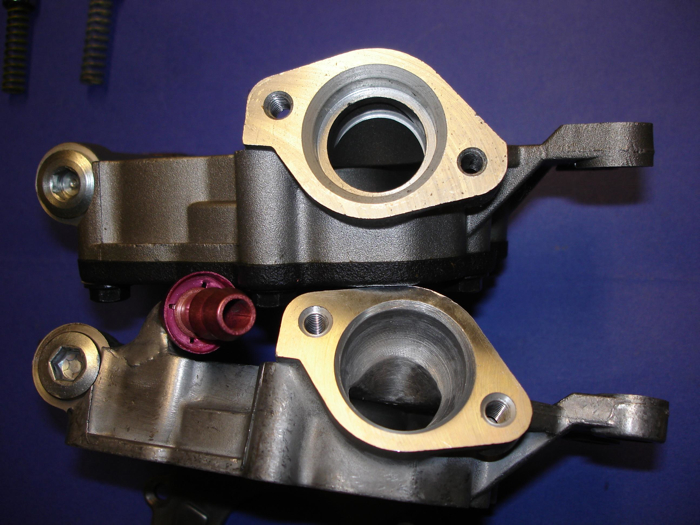

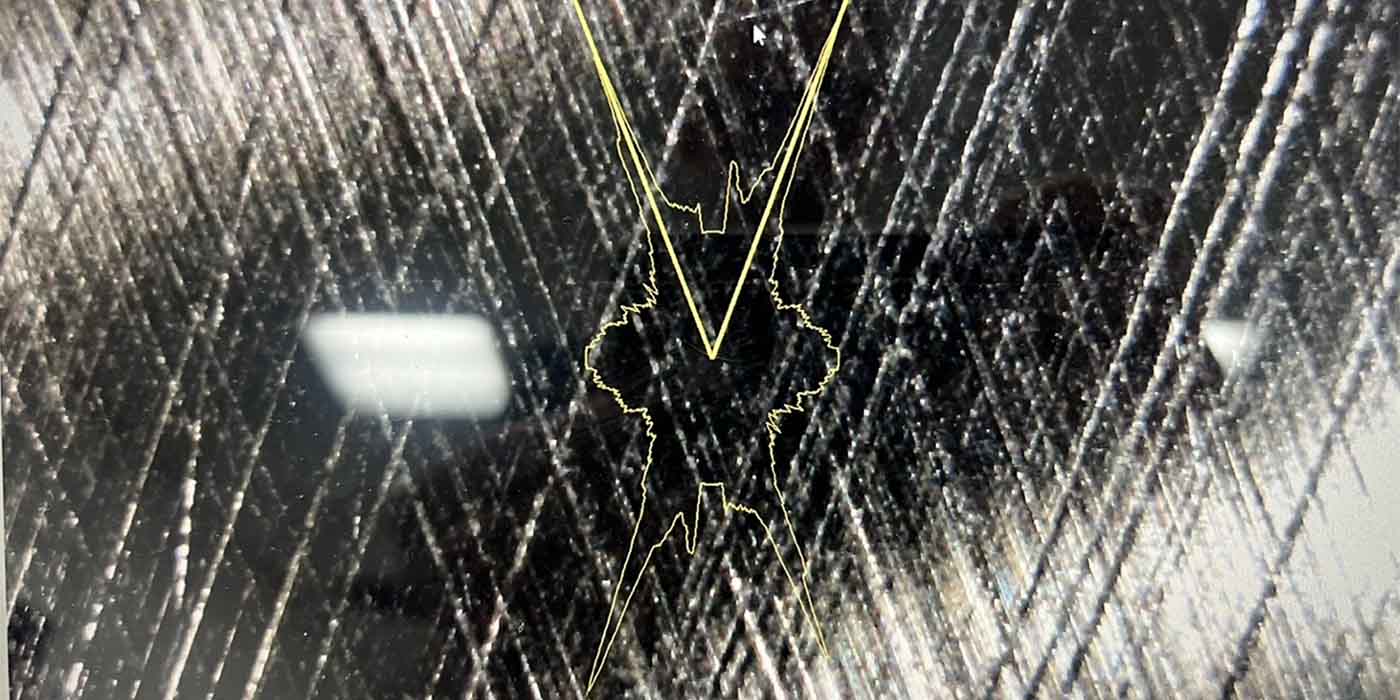

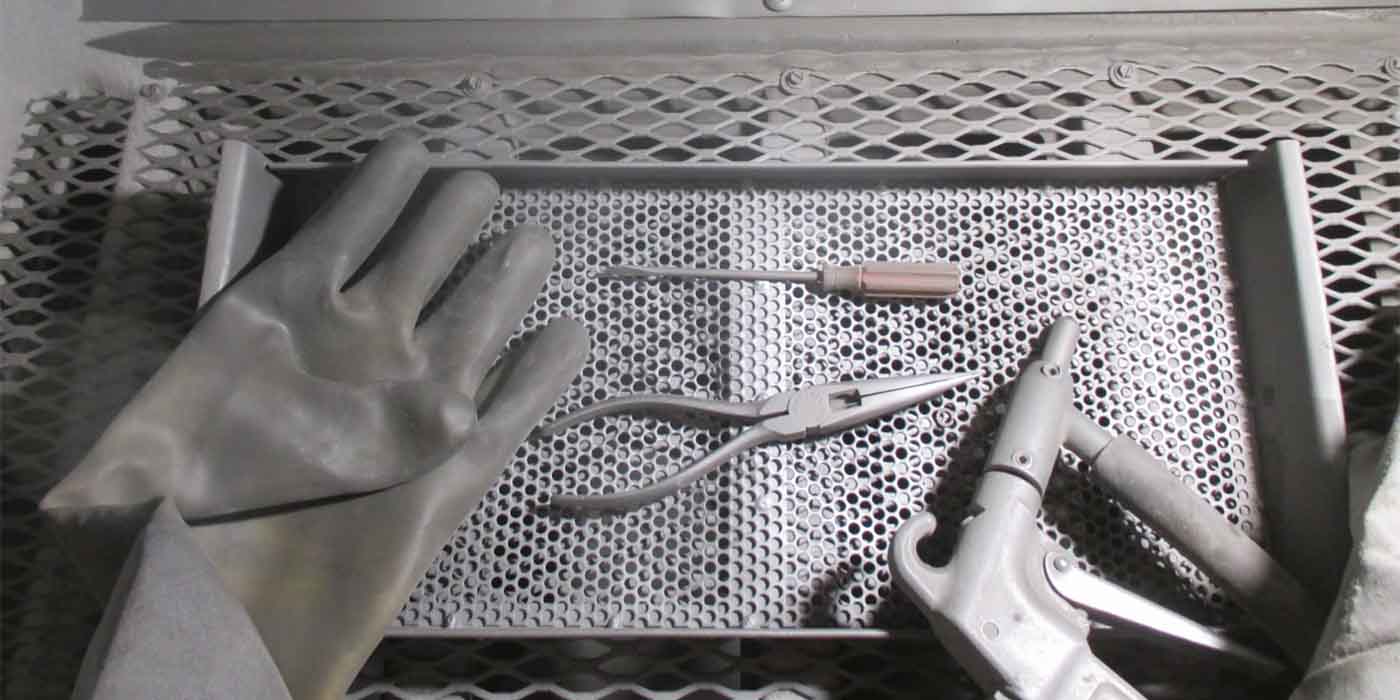

In situations where the rules are very restrictive, your hands may be tied as to what sort of changes or modifications you can do on a customer’s engine. The rules may prohibit any porting or blending of the ports in an oil pump, or using a higher output pump. But even in stock classes that only allow OEM or “OEM equivalent” unmodified oil pumps, most rules allow for a certain amount of “blueprinting” of the pump housing and internal components. This would include things like minimizing clearances between the end of the gears and the housing, select fitting gears to reduce pumping losses, deburring and cleaning up oil inlet and outlet ports (without enlarging the ports or changing the basic configuration), changing the oil bypass valve and spring, brazing the oil pickup tube to the pump housing so it doesn’t work loose during a race, etc.

It’s essential that you and your customer are on the same page as far as the rules are concerned, and that you know what your boundaries are as to what you can modify and improve BEFORE you make any changes. After all, you don’t want to make changes that may end up disqualifying a racer if the engine is torn down for a technical inspection.

If the rules allow a modified pump to be installed, go for it. Some performance pumps include larger inlet and out ports, anti-cavitation slots in the housing and cover to minimize oil aeration and pressure losses at high RPMs, adjustable oil bypass valves and improved valve designs for better pressure control, special bypass ports that reduce pumping effort and improve pump priming, stronger castings with larger gears, or billet steel and aluminum pumps for applications that require maximum strength.

On late model engines with front mounted pumps (Chevy LS, Ford modular, etc.), the factory pump covers are often stamped steel and rather flimsy. These pumps often leak a lot of oil at high RPM, resulting in erratic oil pressure readings. Installing a high quality aftermarket pump with a cast iron or heavier steel cover plate can help maintain consistent oil pressure.

High flow oil pumps may be needed for certain applications, such as engines that use piston or valve spring oilers, or that have Variable Valve Timing (VVT). But these pumps shouldn’t be used as a Band-Aid to maintain oil pressure in an engine that is worn or has sloppy bearing clearances. The last thing you want to put into a high performance engine is a cheap oil pump!

Some Specific Recommendations

To find out what type of oiling systems are recommended for grassroots racing, we contacted various aftermarket suppliers for their advice. What follows is a condensed version of what they had to say.

Within the framework of the rules that apply for a particular type of racing, there are several things that have to be considered. One is what you are trying to accomplish? Are you trying to prevent oil pressure loss, are you trying to control engine oil temperature, or are you trying to accomplish both? What kind of demands are being placed on the engine and oiling system?

If you don’t know what parts are best for a given application, talk to the parts supplier for their input. They design their products for specific kinds of applications and can guide you as to which oil pan, pump or oiling system setup will work best in a given application.

Drag racing has very different oiling demands and conditions than circle track or road racing. Drag motors are fired up cold, make a short full throttle blast down the strip and are then shut down or are driven slowly back to the pits for the next round of racing. The oil never gets very hot, and all the G-forces inside the pan are fore and aft (no side forces). With circle track motors, the engine may run a 10 lap heat, a 25 lap semi-final or main event, or an even longer race. The oil gets hot and sloshes fore and aft and towards the outside right side of the oil pan. Road racing is similar except that the races are usually longer and the cars turn both right and left, which requires different oil pan arrangement.

There are several key design features to a properly baffled oil pan. The first is pickup location. Depending on the type of racing, the pickup location and baffling is critical. Drag racers typically run deeper (taller) oil pans. However, the best pickup location for drag racing is actually in the middle of the sump with trap doors front and back. This arrangement keeps the oil where it belongs when launching off the line and during braking and shutdown at the end of the strip. More oiling issues typically occur at the end of the strip than at the starting line in drag racing because some oil pans allow the oil to slosh forward away from the pickup when negative G-forces occur with braking.

With dirt track racing, the pickup should be located in the right side rear of the pan because the car is always turning left turns. The pan also needs a scraper to help direct oil away from the crankcase for reduced windage and drag. The pan also needs a kickout on the right side to keep the oil in the vicinity of the pickup. A kickout also adds additional oil capacity to reduce the risk of oil aeration, oil starvation and overheating.

In road racing with a wet sump oiling system, a diamond style trap door baffle located in the center of the sump helps control oil sloshing during acceleration, deceleration and cornering. Side kickouts in the pan can provide additional oil capacity as well as lower the overall height of the oil pan so the engine can be mounted lower in the chassis to reduce the center of gravity and overall ride height.

In high capacity oil pans, baffling and a windage tray are essential to keep oil away from the crank. If you just bolt on a higher capacity pan that contains nothing to prevent the oil from sloshing around, it can get whipped into foam by the crankshaft creating drag as well as oil aeration and loss of oil pressure. That’s the last think you want happening in a racecar.

Another upgrade that should be considered when the rules allow it is some type of reserve oil pressure accumulator. An accumulator can provide added insurance against loss of oil pressure when extreme G-forces are encountered (fore, aft, sideways or vertically in the case of off-road vehicles). Guys who are running sticky race compound tires on a road course can really benefit from an accumulator. Just ask the guy who didn’t have an accumulator and blew his engine because he lost oil pressure in the long hard turn.

An accumulator consists of a cylinder with a piston inside. The backside of the piston is pre-charged with nitrogen to serve as an air spring. The front side of the piston is plumbed into the engine’s oiling system. As the oil pump builds pressure it pushes oil into the accumulator, pushes the piston backwards and compresses the air charge behind the piston. This creates a reserve supply of oil pressure that discharges back into the engine when oil pressure drops below a certain pressure. The accumulator can also be used to prime the oil system prior to starting it by opening a manual valve. This reduces the risk of a dry start and metal-to-metal contact.

Dry Sump Setups

Hot oil, especially low viscosity synthetic oil, gets as thin as water and sloshes around quite a bit inside an oil pan during an endurance race or road race. It may be more than a well-designed wet sump system can handle. So it may be necessary to upgrade to a dry sump system if the rules allow it.

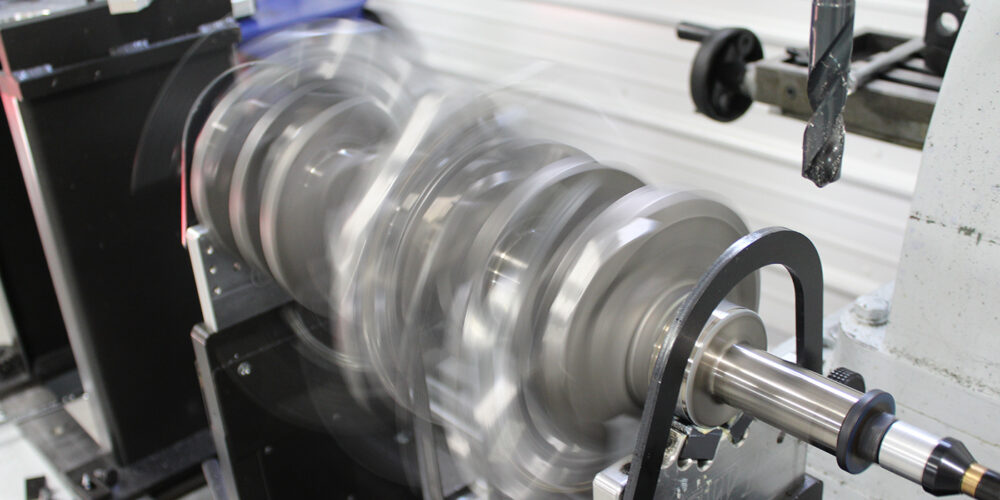

Dry sump systems are the ultimate setup because they eliminate all of the problems that can occur with oil sloshing around inside the crankcase. By sucking all of the oil out of the pan, routing it into a storage canister, allowing the air to separate from the oil, the pump (which is usually externally mounted and belt driven off the crankcase) can provide a steady supply of oil to the engine under even the most extreme G-forces.

The most basic dry sump systems typically include an external three-stage pump (a pressure pump to supply oil pressure to the engine, and two suction pumps to pull oil out of the engine), a shallow custom oil pan with scavenge ports for the suction pumps, and an external oil reservoir. The higher end systems contain multiple stage suction pumps to pull vacuum inside the crankcase for reduced windage and drag. A larger oil reservoir and/or external oil cooler helps keep the oil temperatures within safe limits.

The location and capacity of an oil reservoir tank may be regulated by rules. Most rules allow the tank to be mounted inside the vehicle behind the driver, with oil lines extending through the firewall to connect the tank to the pump and engine. On off-road and road racing applications, a tall skinny tank is better than a short, wide tank because it helps keep the oil from climbing up the sides of the tank (good internal baffling is also important). Some off-road racers even mount the tank on gimbals so it will remain vertical regardless of the attitude of the vehicle itself.

The only real drawback of dry sump oiling systems is the cost, which can range from around $2,500 for a basic system up to $5,000 or more for a multi-stage high end custom setup. Although a dry sump system costs a lot more than a typical aftermarket high output oil pump and modified oil pan, the problems it eliminates and the protection it provides can more than pay for itself.

One dry sump oiling system supplier we interviewed said dry sump systems should be allowed in dirt track racing because it actually saves money in the long run by protecting a racer’s engine. Blowing an engine because a wet sump system failed to maintain good oil pressure in a race costs a lot more than adding on a dry sump oiling system.

Some say its time to change the rules so racers can have the option of running a dry sump system instead of a wet sump system. The competitive advantage of a dry sump system could be limited by restricting the system to a basic three-stage spur gear pump with a maximum length of 7 inches so the system can’t pull vacuum in the crankcase. Open venting of the crankcase and/or valve covers would also be required to prevent the system from pulling vacuum. These simple rule changes could open the door for dry sump systems in dirt track racing while reducing engine failures due to loss of oil pressure. Costs could be minimized by using relatively inexpensive reservoirs and modifying existing oil pans (welding on a couple of suction ports). If you agree, talk to your local racetrack sanctioning body about updating the rules to allow dry sump oiling systems in grassroots racing.

What about street performance, street/strip applications? For most stock and performance street applications, a wet sump oil system works fine. A dry sump system would be overkill and an unnecessary expense. The stock oiling system can be upgraded with a good aftermarket performance pump. You don’t necessarily need a higher flow pump unless you are building the engine “loose” and need more flow to maintain good hot idle oil pressure. The old rule of 10 PSI of oil pressure from every 1,000 RPM is still a good one for most street and street/strip motors. Excessive oil pressure just wastes energy and horsepower, and ends up dumping oil back into the crankcase.