Just as with anything related to engine building, everything is always evolving. The industry is always trying to improve upon the things people did prior, and much of that is continuing education surrounding the many principles of engines and making horsepower. After all, that’s part of the reason most people enjoy it.

A large part of what helps push performance of an engine forward or to new limits in various applications are the capabilities of cylinder heads. When it comes to improving horsepower and rpm, airflow has a lot to do with it, and it seems the job is one that’s never finished – you can always find ways to get more out of a head.

We recently sat down with Matt Bieneman, owner of MBE Cylinder Heads & Manifolds in Mooresville, NC, who has specialized in cylinder heads and manifolds for more than 25 years. We wanted to know what goes into finding more, and better, airflow out of a head. Matt says he starts every cylinder head project by understanding the application, what the rpm is and what the cubic inch is going to be.

“You can’t do anything until you fill those blanks in,” Bieneman says. “Once we figure out what the application is, the rpm, the cubic inch, then we look at the casting or the billet head and we have to work within this window. We look at where the placement of the valves are going to go, because every application is different. In an endurance application, it doesn’t necessarily need all the valve area that it does in a drag race application. What we do is we try to get all our cylinder heads, all our castings without guide bores, because then we can move that stuff around.

“On our 18-degree conventional big block Chevy heads, we have four different guide locations. We have a small port version, so understanding that’s a lot less valve area, we moved the valves closer to each other to take advantage of that and get the valve off the cylinder wall. Things like that are always coming to mind to try and improve it instead of just leaving it where they’re at. It definitely helps. It makes things more efficient.

“On drag race applications, we have numbers that we stick to that we know it needs to be this much off the cylinder wall, especially in a normally aspirated engine, if it’s going to accelerate. You can have the valves in the wrong location. If you have the valves too close, it will still make really close to the same power, but it will not accelerate and it will be slower on the track. It will run less mph, but it’ll make similar power. It’s kind of interesting.”

When it comes to cylinder heads, MBE does a little bit of everything. In fact, the type of cylinder head doesn’t matter much to the MBE team whether it be a Chevy, Ford, Dodge or something else. As long as they know what the bore size is, the application and the rpm, the type of head really makes no difference.

“I always felt like the learning curve would be so much better if you could learn all about these different applications, then all that knowledge should be able to help the other applications,” Bieneman says. “For instance, now we’re in the marine head market, and knowing those cross-sectional areas are dictated by cubic inch and rpm is huge. The rpm has much more to do with it than the cubic inch does. You have to make big moves with rpm compared to cubic inch.

“During our development work for some of the Cup teams in the mid-2000s, we learned that when the rpm went up, the plenum volume had to get bigger. When we did the NHRA Pro Stock stuff, part of the reason we were successful at it, is because we were privy to all this information we had seen in other applications. It helped us immensely.

“As rpm goes up, the cross-sectional areas have to get bigger, especially on the intake side. On the intake port itself, as the rpm goes up, the port has to get bigger. A lot of people make it bigger in the wrong place. A lot of people make it bigger where it’s the easiest and that’s at the intake flange. However, that creates taper and it creates problems. That makes it lazy. It just doesn’t respond. It still has to pull fuel.”

Of course, a larger port isn’t always the answer. Take for instance dirt racing where the engine is at 3,500-3,600 rpm on restarts. The port has to be significantly smaller to achieve the desired results those guys are looking for. To continue to find ways to make the most efficient head they can, MBE gets the guide location set and then figures out the valve angle and the port height.

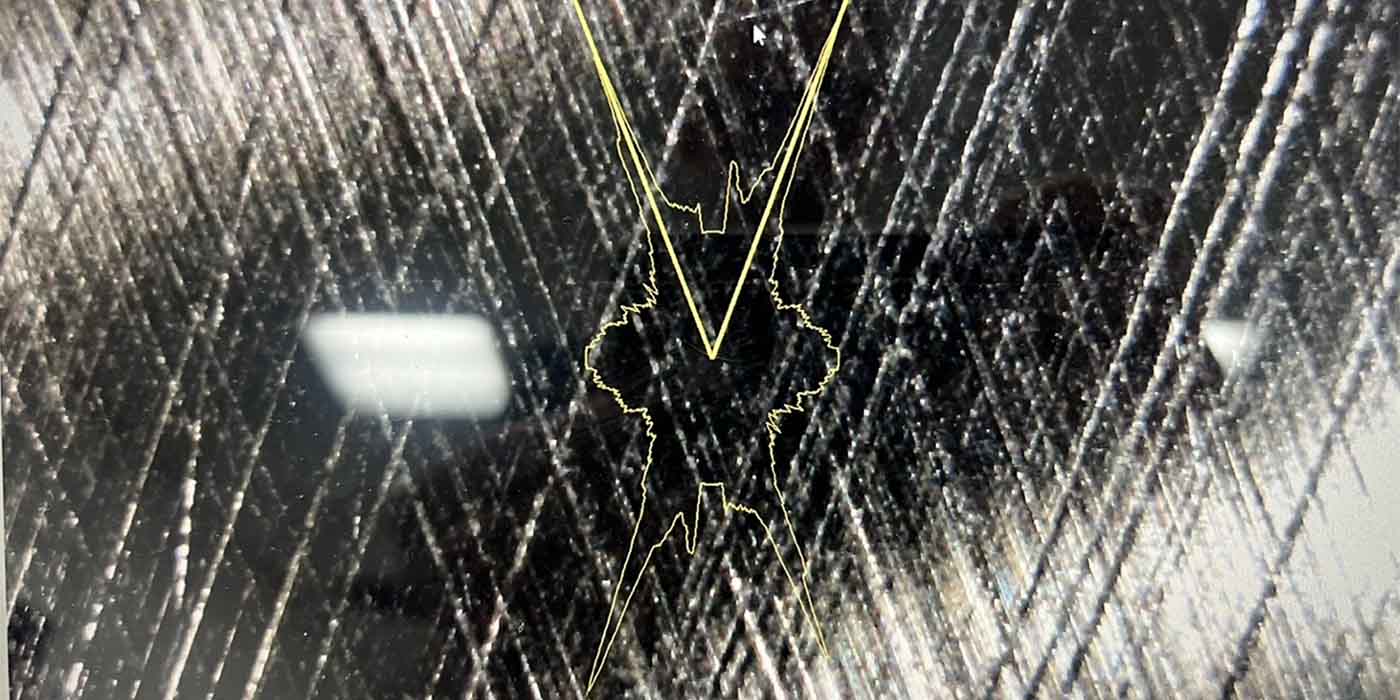

“We analyze the valve angle because that’s going to determine what we do with the chamber,” he says. “Then, we look at the port height because that’s going to determine what we do with the chamber also. We will look at the valve lift because that’ll dictate what we do in the throat of the valve job. From analyzing all of that, we have an idea before we start, what it should flow. When it’s wrong, we know we have more work to do.”

In anything that’s approximately less than 10.5 degrees – the valve angle to the deck – all the mid-lift numbers are going to be sacrificed because you have to create area from the valve to the spark plug side of the chamber. You have to create area for the airflow.

“When you don’t have those steeper angles, then you have to create area back there,” he says. “All of us do it, we ‘scoop’ that area out on that spark plug side. It would be great if we could come flat off on the valve job, but we can’t. When we have the 10-degree stuff and less, when we can do that, what happens is when the valve opens, it’s not going towards the spark plug as much, so it creates area back there and then we can come what we call flat off. Basically, the chamber becomes part of the valve job or an extension of it. When you can do that, you create huge mid-lift numbers and there’s a huge advantage. You can do it, but you’re going to have to work hard and find the reasons why.

“We know what the mid-lift numbers are going to be if it’s a flatter valve angle, and we know what the sacrifice is going to be if it’s not. We know what those areas need to be, and then we know what the areas need to be in the throat, so we go to the throat. Now, we’re in where the valve job is, so the smallest part of the port, which is right underneath the valve – about .300” below the valve.

“We know what that area needs to be depending on what the valve lift is and the application and all the other things like port height, because the valve goes across differently at different port heights. Not every valve is treated evenly either. Those back angles make a difference. Those are very, very important. We spend time on that. The lengths of those angles, if it has one back angle or two back angles, it’s for a reason when we do it. It’s not just random. We do it for many different reasons. You can use one back angle on an intake valve and it’ll create more cross-sectional area. It’ll make the valve stronger.

“We can put two angles on it and it’s going to pick up airflow, but if it’s only going to pick up so much airflow compared to how much strength we’re going to get in the valve and we can take the weight out of the valve, then we try to look at that because maybe one angle is better. Taking the weight out of it allows someone to run more rpm. The car will go faster with the rpm – that’s the way we’ll look at it.

“That decision is based on rpm and whether the engine has a power adder on it and the port height, especially at the spring pocket, dictates if it has one angle or two angles. The shorter the port or the less the intake port is raised, we feel the air goes across the valve in different ways, and so we look at it differently. Some stuff does only have one angle and it’s because of what we feel is correct.

“Those angles are very important because the air has to stay attached, and rpm dictates a lot of what the width of those angles are going to be. As the rpm goes up, typically the width of the angles needs to be wider to keep it attached.”

Something to keep in mind is not every head is efficient. A conventional big block Chevy is completely inefficient. It doesn’t work like other cylinder heads do – not like a good one does – according to Bieneman. Therefore, MBE does different valve jobs to make sure the throat is the correct size for the ‘box’ they’re in and for the lift and application.

“Then, we go to the next level, which is the bowl or the area at the top of the guide,” Bieneman says. “We know exactly where we’re going to be or need to be there before we start on a model. We stick to it because we know then it’ll accelerate on the track. It’ll pull fuel and it’ll be efficient. A lot of people get the bowls too big and it looks great on the bench, but it’s not what the engine wants to see.

“Then, we’re looking at how big does it need to be over the short turn. By this time, we’ve already figured out what the size of the opening is at the flange. We did that before we even started on the chamber and everything, so we know what radiuses we’re going to use. We know what the width and the height of the port is going to be. We’ve already done all of that. We’re just connecting the top – the valve side to the flange – and then just working the middle.”

While the intake port usually gets a lot of attention, be sure you’re not ignoring the exhaust port and ways to make that more efficient also. As has been mentioned, be sure that the flow bench isn’t your only guiding light.

“I’m a firm believer on the exhaust side that you really have to be careful with the flow bench,” he says. “The flow bench will tell you what it will flow, but it doesn’t dictate what the engine does. We’ve changed the shape of exhaust ports before with bigger radiuses on the roof and anything to try to make it more efficient. We’ve done this a few different times and did the testing on it. It didn’t flow any more air. It flowed the exact same amount.

“On our 18-degree conventional stuff, we did this to make it more efficient, and it picked up 30 horsepower at peak and didn’t lose any in the middle. The bench doesn’t tell you any of that. That’s the problem. It flowed the exact same at every lift. On the exhaust side, shape is extremely important. Of course, we’ve learned over the years that throat size is even more important.

“In the past, if it was only .500 lift, we’d look at the flow bench and say it needs to be huge radiuses and a small throat because that creates low lift. The bigger the radius you can put underneath the exhaust, the better the low-lift stuff is going to be. Or even at .500, it’s going to be significantly better. But, what you learn is you can kill that thing by 30 cfm and make the throat bigger and pick up power. It’s not about the pressure that you flow it at. It’s about the dynamics of the engine and where the piston is and what it’s doing at that time. Experience helps on the exhaust side and we all do things a little bit differently, but typically, if it looks right, it’s probably right.”

When it comes to cylinder head work, many view it as a sort of black magic or art form because of how many different ways there are to go about trying to achieve your desired results. However, there’s no replacement for experience and finding the truths over time.