Those of you who know me are aware that I’m a scientist, not totally unlike the guy from the Big Bang Theory. I’m a physicist by training (M. S.), but I’ve always worked as a mechanical engineer, since I’m such a motorhead.

With a background like mine, I’m not much on sales presentations. I’m much more comfortable with real data, not BS; and qualified people, not marketers, to evaluate when attempting to draw conclusions.

This sometimes gets me in hot water in the oil industry (and not to mention with certain magazine editors)!

One of the presentations made at this year’s SEMA Motorsports Parts Manufacturers Council (MPMC) Media Trade Conference really caught my attention. For years we’ve had technically developed racing oils competing in the marketplace with armchair formulated racing oils (usually a fully formulated oil plus ZDDP), ZDDP supplements, diesel engine oils and European oil formulations. One of the premier racing oil developers finally took the time (18 months) and spent the money (megabucks) to quantify the performance differences between these various products. This is some great, useful science!

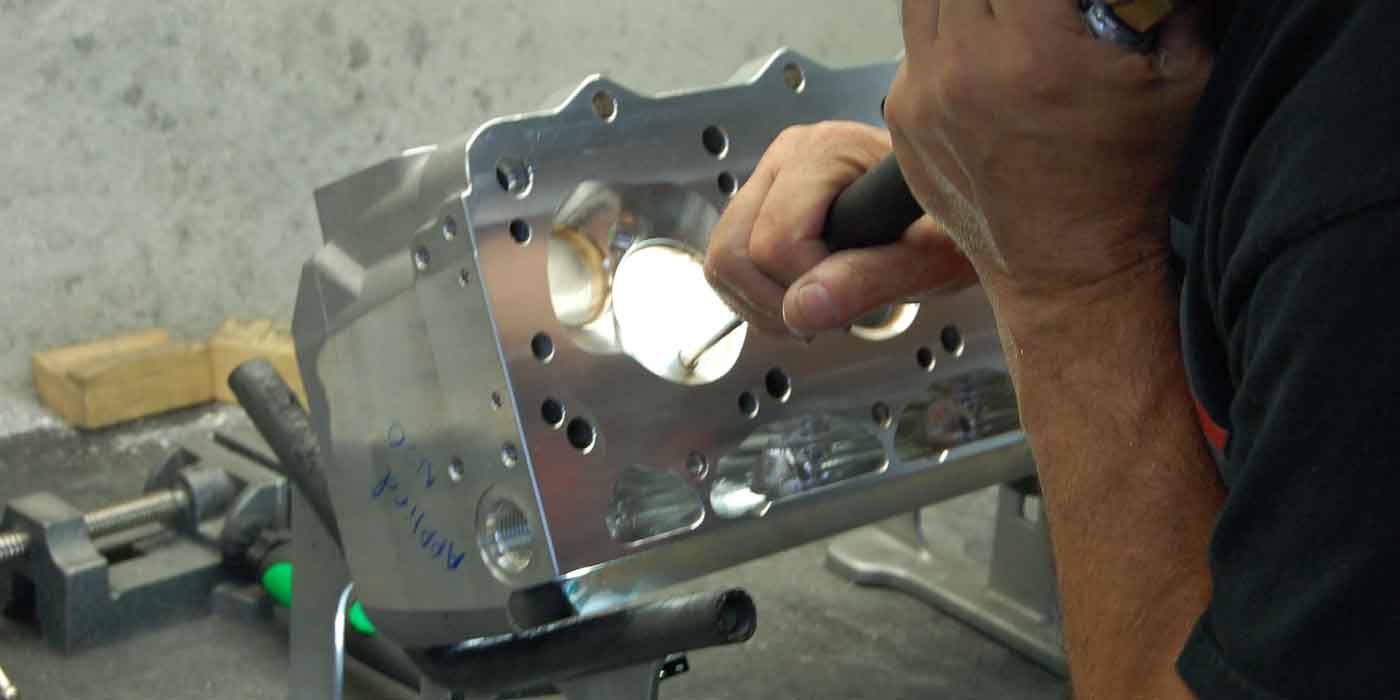

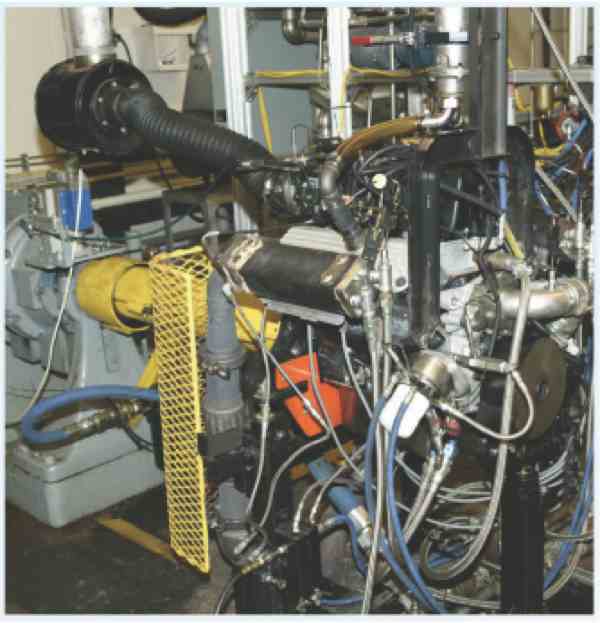

First, let me give you a little lube oil testing background. All oils that wish to obtain API SN, CJ-4 or ILSSAC GF-5 credentials must pass the ASTM Sequence IIIG test (Figure 1, above). Notice that this test utilizes a 3.8L Buick V6 engine with a flat-tappet cam and only 0.325˝ valve lift. Valve spring pressures are only 205 psi open. Not many of these engines can be seen on the racetrack.

Compare these operating conditions to your race engine. NHRA Pro Stock engines utilize about 0.600˝ cam lobe lift (1.1 to 1.2˝ at the valve) and valve spring pressures approaching 1,500 psi open. Realizing that most racers use cams with about 0.500˝ lobe lift and lesser spring pressures, these laboratory engine tests were conducted to reflect the more typical cam lift/ valve spring pressure conditions.

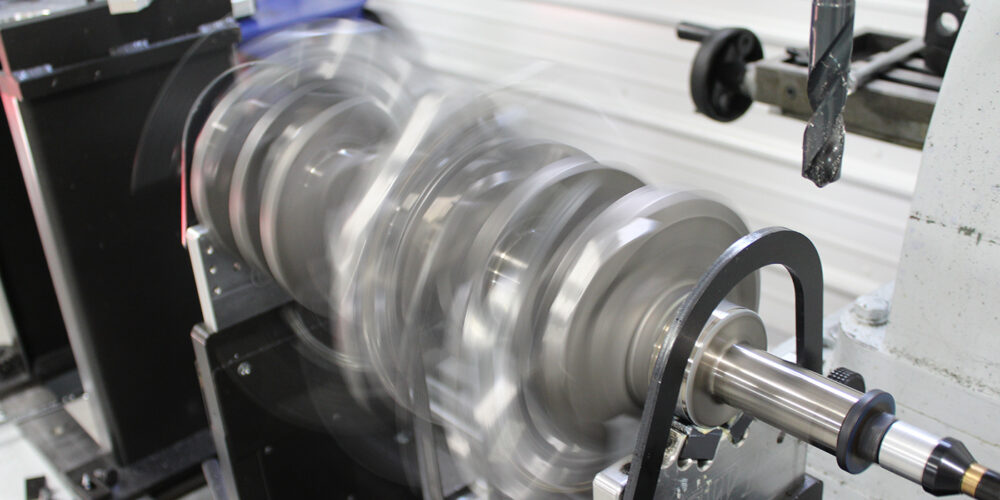

A carefully built small block Chevy engine was repeatedly tested with the conditions as shown in Figure 2 ( at left). The engine utilized small base circle cams with 0.492˝ lift and 300 psi open valve spring pressures.

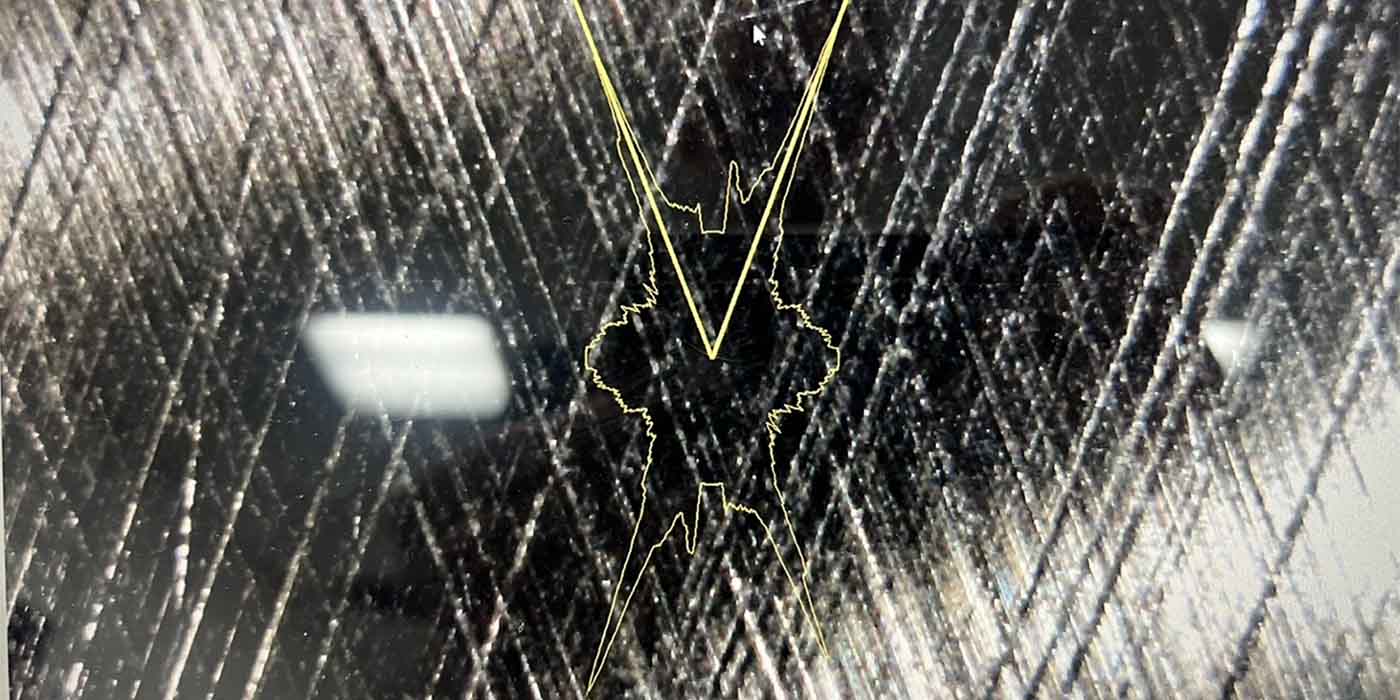

The tests included both a break-in cycle (lasting 30 minutes) and a 2-hour durability cycle with a full power pull every 5 minutes. All test cams were prepared identically with no coatings and measured prior to break-in, after break-in, and upon completion of the durability test using the Adcole 911 precision camshaft measurement apparatus (an incredibly accurate measuring device). Break-in oils were used if the race oil supplier provided them.

Eighteen months of testing produced many pages of graphs and tables of data, which I will not bore you with here. Instead, I will relay my impressions of what this data showed me.

The data obtained during camshaft break-in showed several interesting results. A major API CJ-4 SAE 15W 40 diesel engine oil actually failed 5 cam lobes during the break-in (a fail was determined to be over 30 microns cam lobe wear).

This isn’t really as surprising as I initially thought.

We know that typical API SN gasoline oils don’t have sufficient ZDDP to protect cam lobes, but API CI-4 and CI-4 plus diesel oils usually had sufficient ZDDP. However, with the advent of the new API CJ-4 and CK-4 diesel oil specifications, a limit of 1.0% wt sulfated ash (SA) was established for emissions reduction. The sulfated ash of a diesel oil is the sum of sulfated ash contributed by both detergent and ZDDP.

In essence, this places an upper limit on ZDDP content since diesels need higher quantities of detergents. We now know the new CK-4 oils cannot adequately protect flat tappet cams and lifters when new. Good info.

Interestingly enough, a new API CK-4 oil was tested with added ZDDP. It also failed the break-in test with two bad cam lobes. This indicates, as I have said on many occasions, that adding ZDDP does not guarantee cam and lifter protection. ZDDP must be added to the oil under controlled conditions to prevent its premature activation. No other oils failed the break-in test limits.

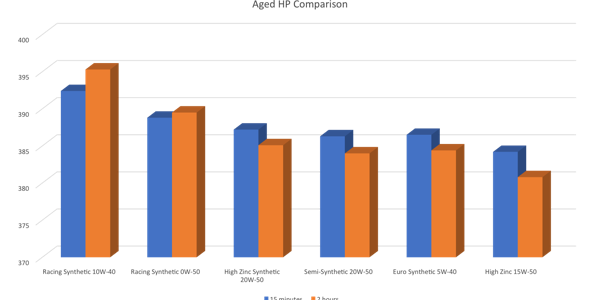

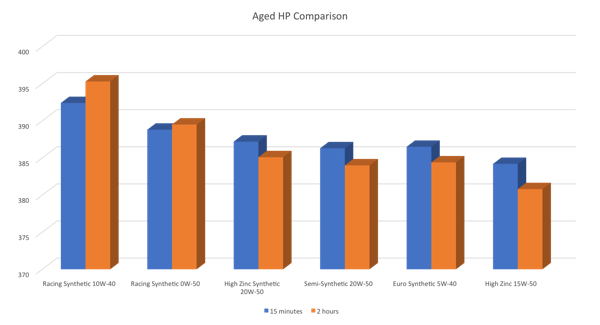

Interestingly, the validity of using break-in oils was verified. Even the poorest performing break-in oil provided a quarter of the wear seen with the best racing oils not utilizing a break-in oil. One break-in oil provided a third of the wear of the other two break-in oils. When every 0.001˝ of valve lift produces additional horsepower, break-in and operational wear should be minimized. This can mean a lot of horsepower after significant engine operation (see Figure 3, above).

Now to the good stuff. I am familiar with virtually all of the racing oils tested. I noticed that two of the racing oils, which I know to be arm-chaired formulations, produced roughly five times as much average cam lobe wear as did the racing oils developed using science and laboratory engine testing. Marketing claims don’t guarantee good racing oils. In fact, one of these oil marketers has since requested that their additive supplier switch them to a more scientifically developed formulation.

I won’t tell you who this is, but if you conduct elemental analysis on new oil samples, you will observe changes in the elemental composition (Calcium, Magnesium, Phosphorus and Zinc) of this racing oil before and after the switch in additive packages.

It was also interesting to observe that heavier oils (e.g., SAE 15 W-50) provided more wear protection than the lighter racing oils.

Although the differences weren’t catastrophic, the engine builder must always balance up-front horsepower with long-term longevity. This is why NASCAR engines don’t run oils as thin as NHRA Pro Stock racers do. In one case, you need over 500 miles of valve train durability. In the other case, you only need 5-10 miles of valve train durability.

All-in-all, this was very good oil testing data to peruse, and I was able to verify a lot of things I had always felt to be true. Be very careful when selecting racing oils for your engines – remember, “Engine Lives Matter.”