Life is all about balance. You balance work with fun. You balance family and friends. You eat a balanced breakfast – sometimes. It’s all hanging in the balance. Well, if you’re an engine builder, you also balance engines, specifically crankshafts and rotating assemblies.

A quality balance job is a feel. If you’re driving down the road in a car with an unbalanced engine, you’re going to know something’s wrong real quick. On the flip side, if you’re driving down the road in a vehicle that’s been properly balanced, you won’t feel a thing. It will feel smooth, no matter what you do with the accelerator. That’s the feeling engine builders and their customers are after these days.

“We’re very particular about balancing,” says Skip White, owner of Skip White Performance in Kingsport, TN. “We like a nice, smooth engine. We do motors that are into the 8,000 – 9,000 rpm range and we don’t have any problems. I love that smooth feel and we try to get that to customers by doing a good job of balancing and having excellent equipment.”

Today’s engines are lighter, have more power than ever before and run tighter tolerances, which is changing how balancing impacts the rotating assembly. The actual process of balancing may not have changed much recently, but after speaking with a few industry professionals, there are several topics engine builders need to be paying attention to in order to balance the right way.

Higher RPMs Require a Better Balance

Regardless of who does it, balancing has always been one of those things that is needed. There’s a formula for your bob weight, which on a V-type engine is 100 percent of rotating mass and 50 percent reciprocating mass. The principle of balancing as far as the formula is concerned has pretty much remained the same, and at the end of the day, the key to the whole thing is symmetry.

“When you’re adding power to the engine, guys realize balancing should be done,” says John DeBates, owner of Auto Machine, Inc. in St. Charles, IL. “With a lot of my restoration work, those guys want to be able to put a coffee cup on their valve cover or intake manifold and not see a ripple with the engine idling at 400 rpm.”

Auto Machine’s customers aren’t the only ones who want to get that silky smooth engine. Skip White Performance even takes its balancing offerings to another level.

“We offer our race balancing procedure, which really takes it to the next level,” White says. “We can’t do the race balance on every motor, so we do a standard balance job too, but when we do race balancing, we tweak every rod and every piston to less than half a gram.”

Most rotating assemblies from a manufacturer come with a basic balance that has the rods at a 1.5-2 grams variance and the pistons at .75-1 gram variance. While some people might claim that isn’t balanced properly, the truth is, you’re not going to get it much closer.

“Nobody in the industry does that,” White says. “You will not believe how few cars on the planet get a closer balance than that. When you buy a rotating assembly from anyone, they keep their tolerances usually around 2 grams on rods and pistons. We check all those and if they’re over that then we correct it, but we’re not getting down to a half gram on all those parts unless they pay us to do so.”

White charges an extra $125 for a race balance on top of his standard balance fee.

“A race engine that does 7,000-8,000 rpm or more will benefit from a balance like that, but it’s erroneous to think that balancing should always be done like that on little street rod motors. It’s nice if you want to pay the money, but it’s not necessary,” he says.

Still, balancing today is more crucial than in decades past simply because rpms are going up on engines these days. There was a time when Corvettes redlined at 5,000-5,500 rpm. But if you modified that motor with a bigger cam and bigger heads, you’d get the rpm range up to 6,200 or 6,500, and then balance can become a problem.

“All that roughness gets magnified,” White says. “There are charts that show how many pounds of force imbalance creates. If you’re turning the motor 20 percent more rpm, the pound force of imbalance does not grow 20 percent – it grows exponentially. That imbalance is highly disruptive to the motor and easily felt. That’s what happens with imbalance – it grows like a monster, but not proportionately to the rpm.”

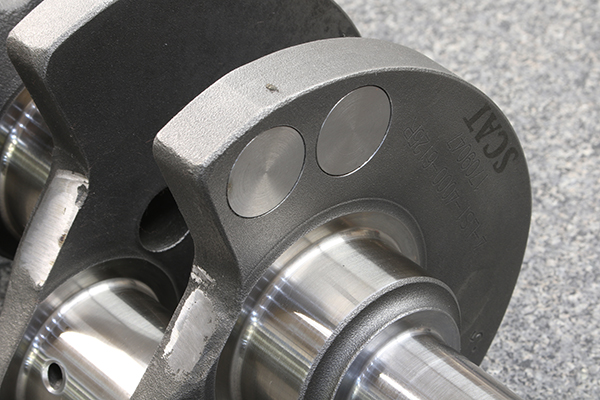

Tom Molnar of Molnar Technologies, a manufacturer of cranks and rods, agrees that an out-of-balance crank can be extremely destructive in today’s engines.

“If you go back far enough, to the ’20s, crankshafts back then didn’t even need counterweights on them,” Molnar says. “They turned 1,800 rpm or something. As the rpm goes up, the balance becomes much more critical. If you go from 2,000 rpm to 4,000 rpm, the loads and forces on the crank don’t double – they quadruple. If you go from 4,000 to 8,000 rpm they quadruple again. Balancing becomes a much more critical factor.”

With what engine builders are capable of making an engine do today using better cylinder heads, larger runners and bigger cams, balancing has to be done to decent standards.

“We use good components,” White says. “Using cheap components will get you in trouble. The biggest enemy to the rotating assembly business is low-grade parts that are on the market. Some people think our kits are overkill. They’re not overkill, and we learned that the hard way. We tried the lower-grade parts and the failures were huge. So we use good parts, good balancing technology and good equipment.”

Hot, Cold, Just Right

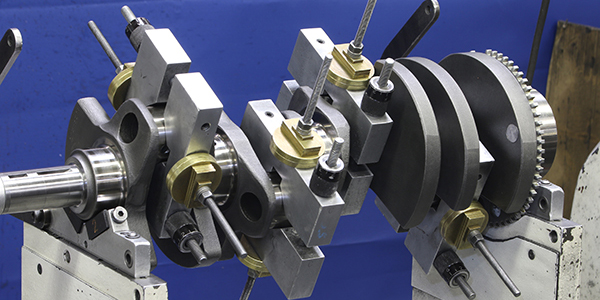

Since balancing has become more critical, it is important to know what constitutes a balanced rotating assembly or not. If you look down the nose of a V8 or V6 crank, you’ll notice that the counterweights are like a corkscrew and that’s because they react with each other through the system of the crank itself. If you understand that then you can understand where to remove the metal.

“When a crank is too heavy in one place, that means it’s too light in another,” says Tom Lieb, founder of Scat Enterprises. “Being able to look at a crankshaft and understand where that weight is and make those decisions – not everybody can do that.”

Not only that, but there’s a lot of language with balancing, so what do you believe? You can measure in grams, grams per inch, inch ounces, etc.

“The fact is pistons are balanced within 2 grams,” Lieb says. “The rods are balanced plus or minus 2 grams end for end. Most people don’t know what a gram is. One gram is 1/28 of an ounce. The actual weight of a gram is the weight of a dollar bill. When people talk about balancing within half a gram or balancing to zero, it’s nearly impossible to do that with 100 percent accuracy. If they take that same thing that they supposedly balanced to within half a gram and put it back on the scale, they might find out they’re half a gram off. You have to understand the repeatability of the scales of the equipment you’re using and how minute it is.”

Now, Lieb stresses that engine builders shouldn’t be discouraged from striving for doing the best, but balancing within half a gram is unnecessary.

“There’s a point of being practical and there’s a point in being fanatical,” he says. “Again, the key to balancing is having each end of the crankshaft being equal. With balancing today, there’s no question the machines make the job a lot easier. However, if you’re balanced down to within a gram or two, then you’re good to go.”

The standard benchmark is ISO 1940/1 that covers rigid rotors. Within that there are three criteria. The first one is the cumulative weight of the rotating mass.

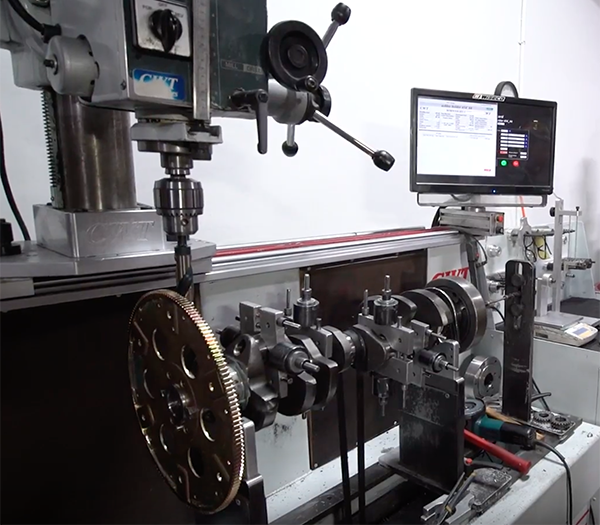

“The spec is set by the cumulative value of rotation – everything from pulley to converter,” says Randy Neal, owner of CWT Industries. “From there it has to fall into a quality grade. A quality grade for crankshafts happens to be 6.3. Then the next one is the peak rpm. All of our software has that formula base built into it, so a customer enters those three values and it spits out the ISO standard.”

That standard is what engine builders should be aiming to at least be equal to. If you stay above that number you’re compromising the balance, and to go below it is more a form of entertainment, according to Neal.

“In other words, if it says 2 inch ounces and you go down to .01 inch ounce, your ego is in check, but your benefits are nil,” Neal says. “There is some potential of improvement, but from a decimal perspective it’s very small. By the same token, a guy might say, ‘What if I go above the standard, but really close to it?’ I get it, but that’s still not the goal. The pro goes for at least the standard minimum, and then he will sneak underneath that at will. When you get a quality balancer, those answers are not only predictive, they’re repetitive, they’re accurate and more importantly they’re gaugeable so we can go back and actually put standards to them.”

The Right and Wrong Way to Keep Your Balance

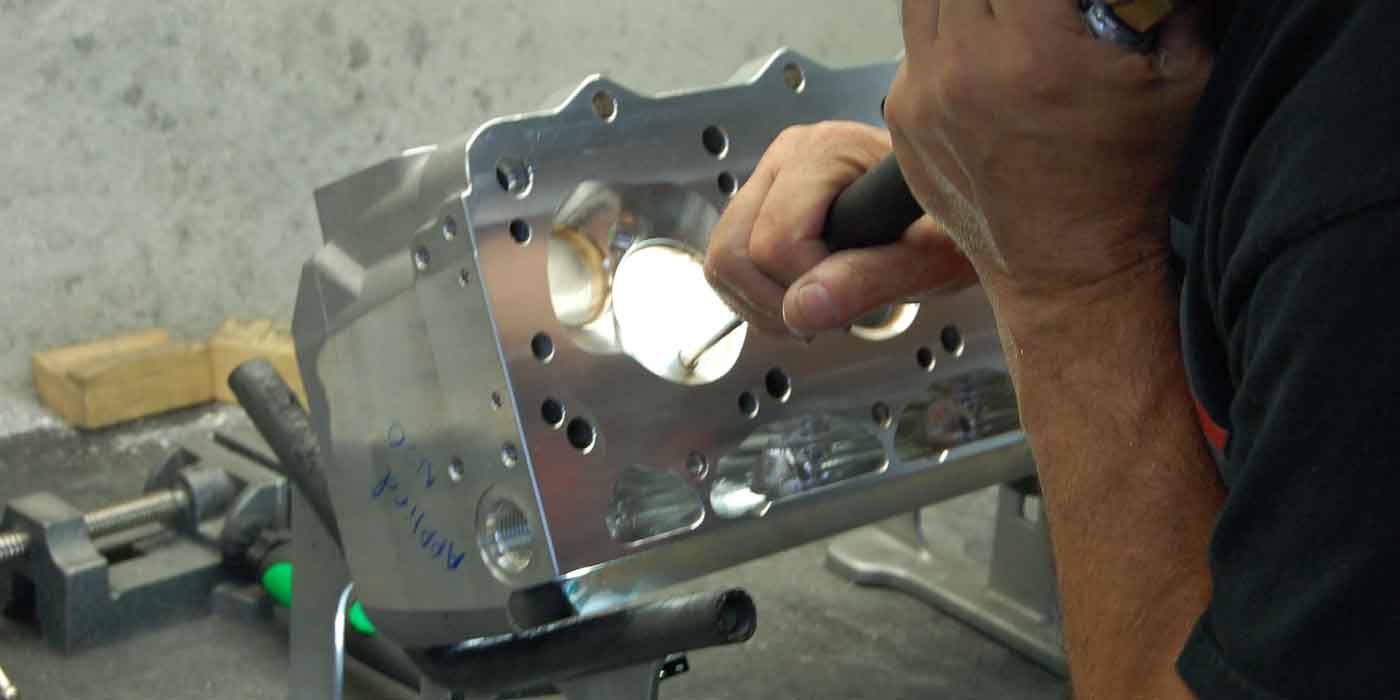

While getting your rotating assembly balanced to within 2 grams or less may be the standard, there are still right and wrong ways to achieve that balance. When you find something is out of balance, you have to have a means of correction, and that correction process is another avenue of change today.

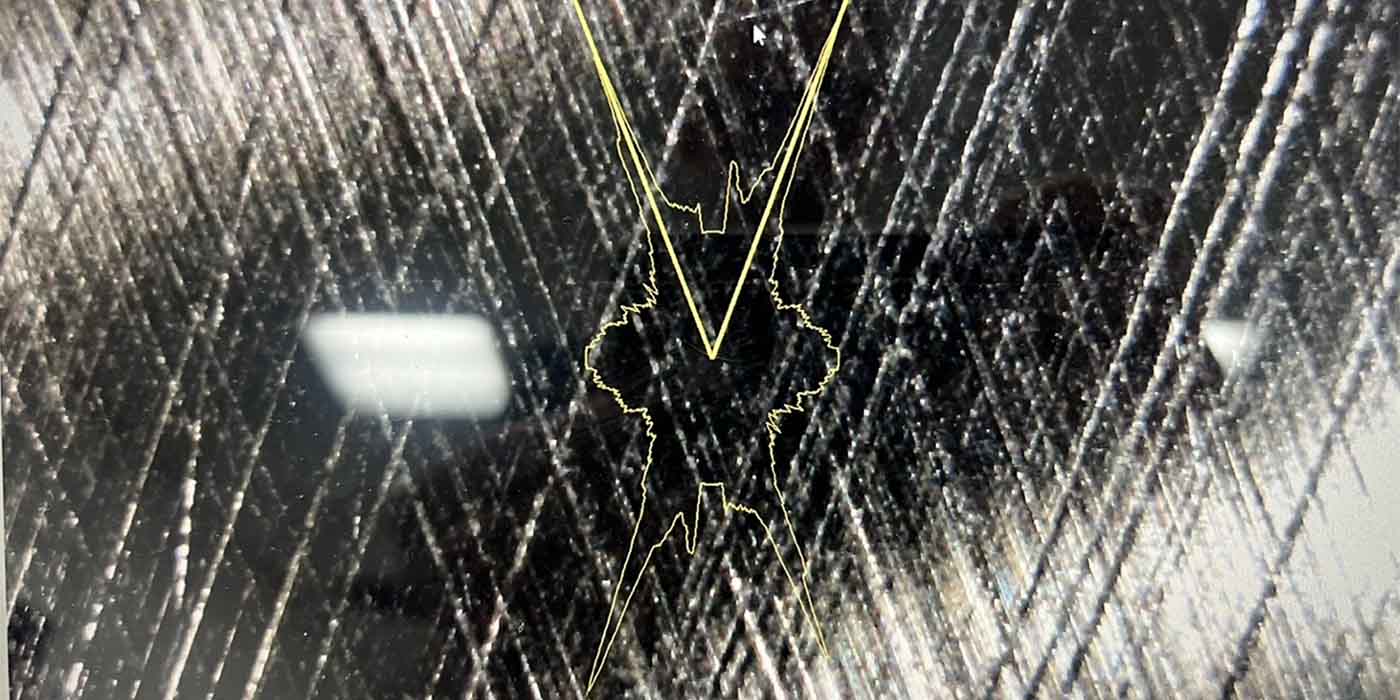

“We’ve always had drills on the machines because it is a quick means of remedy to get rid of mass,” Neal says. “The problem is that most of the cranks we’ve seen literally look like Swiss cheese because they’re taking weight out of them. That’s really the wrong thing to do. What happens is you actually deplete the efficiency of the counterweight. The counterweight is not just there to counter the amount of mass against the piston-rod assembly. It’s also a mechanism that helps control torsional activity. By drilling holes, especially a lot of deep holes, you take that potential away from the crank design.”

Tom Lieb of Scat agrees that too many cranks come back looking like “someone took a shotgun and fired at them.” What you’ve effectively done is destroyed the counterweight system.

“Removing 20 grams to correct your crank is one thing, but if you get into the 75, 100 and 150 grams, which requires half a dozen holes, stop and ask a question of the manufacturer,” Lieb says. “It’s like being a carpenter – measure twice, cut once. It’s the same thing with balancing. If something isn’t right, don’t touch it, because once you touch it the manufacturer is not going to back you up because you went beyond a point of return. So stop, ask a question and we’ll walk you through it.”

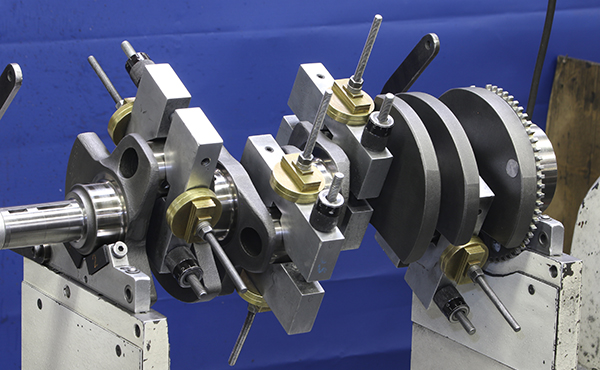

The out-of-balance condition in the crankshaft starts at the center main and works out in both directions. Balancers only detect the out-of-balance condition on the end of the crank.

“The crank is out of balance from the center main out a little bit each way,” Lieb says. “When you get a crankshaft that’s a little goofy on you, you’ve got to start looking at the other counterweights to correct it. The balance machine is telling you that it’s out-of-balance summation-wise at a particular point on the end. But when you see that point is not on center line and it’s moved off in one direction or another, then you’ve got a counterweight in a throw somewhere between there and the center main that you have to correct to rotate it back.”

To counteract “over drilling,” CWT developed new software program methods of removing counterweight shape, not only in a radial, but also to the actual structural shape.

“We have two paths – one is using a crank grinder, and the other is using a body grinder to attack the outer extremes at what we call the wings, and we’re now taking that weight away as opposed to drilling,” Neal says. “Our software basically steers the operator towards a remedy. It’s not just guessing, grinding and seeing what happens. We actually plot that out in the software. In doing so, we’re trying to keep the counterweight more as a single unit that is not perforated and deformed. We’re also talking to people about how to take that weight off.”

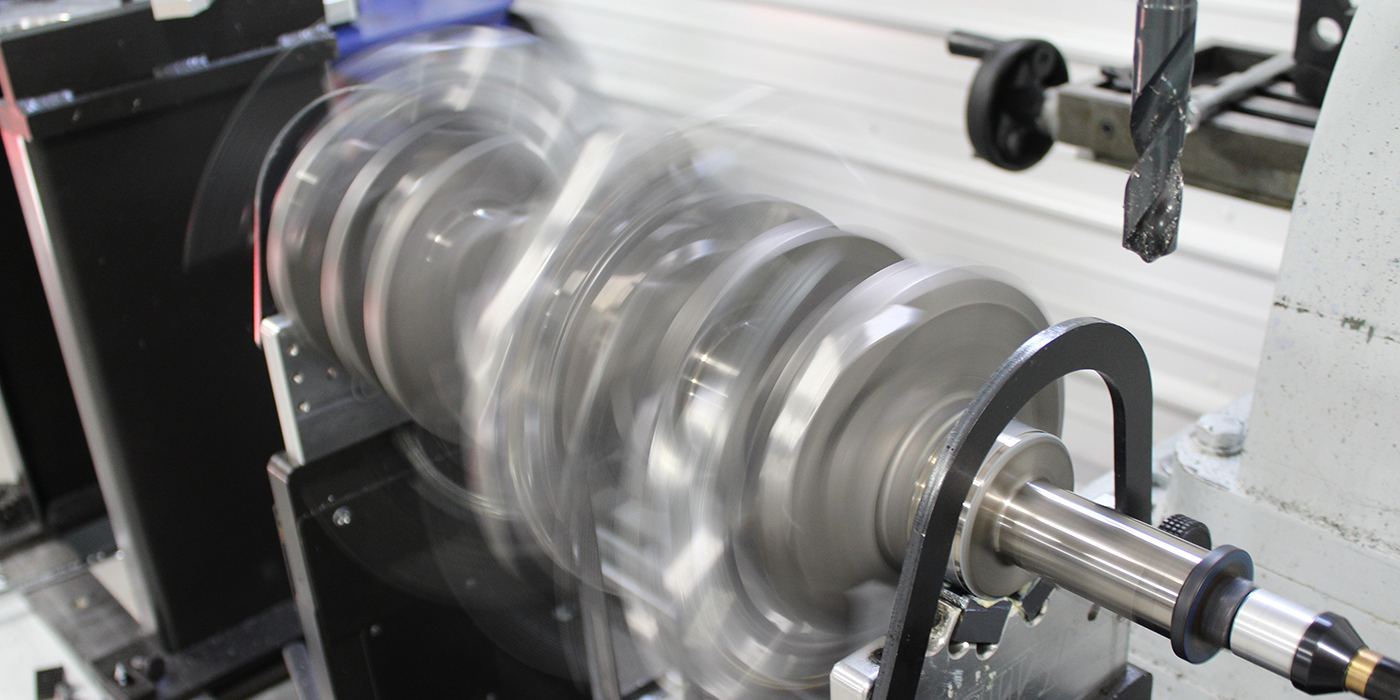

When manufacturers such as Scat or Molnar balance a crank for a certain application and ship it off to an engine shop, there is no further balancing that crank needs. From there, an engine builder is merely making minor tune-ups in the rotating assembly.

“When we balance the crankshaft, it’s a done deal,” Molnar says. “They do not need to be touched balance-wise at all after that. We balance to .18 inch ounces. Some of the machines out there want to look at grams, but that has no meaning whatsoever. It’s the equivalent of tightening a bolt by putting 10 pounds of pressure on the wrench. However, is that wrench 6 inches long, 12 inches long, or 24 inches long? It’s still the same amount of force, it’s just that it becomes much more critical the further out you get. If you’re balancing within an X number of grams, you have to know if that is X number of grams one inch from the center line or is it three inches from the center line? It’s entirely different.”

When you balance a crank you really want to be working in inch ounces, which is how much of an ounce is so many inches from the center line.

“You’re taking the weight out on the outside of the counterweight, but it’s how the force is measured,” he says. “When we balance to .18 inch ounces – that’s .18 of an ounce, one inch from the center line. If you go out three inches from the center line, that’s .06 of an ounce.”

Balancers such as CWT’s read out in inch ounces so you know how much metal you have to take out or add if that may be the case.

Balancing is a Profit Center

Knowing how to do a good balance for your customers is a win-win scenario. They get an engine that will deliver top performance, and you get a happy customer paying for an extra service. Shops such as Auto Machine, Inc. are finding they’re doing more balance work recently.

“We’re finding a lot more balance work than we did 15 years ago,” DeBates says. “A lot of my restoration work I just automatically balance it. The main thing right now we see a lot of is the 4-cylinder and the V6 Nissans, Toyotas and Mitsubishis.”

The import market appeals to a younger crowd that enjoys adding turbo kits, better crankshafts, better connecting rods, pistons, etc. They seem to understand that a balance job will help their engine perform.

“We don’t have to sell it much anymore,” he says. “Most of my clientele coming through the door will ask if we can do a balance job. Once we say yes, they go, ‘OK, add it to the list.’ Part of that I think is social media attention and more articles in magazines about balancing and the benefits of getting something balanced.”

On top of more balancing work being done, shops are also finding that balancing work can be one of the better profit centers.

“It’s probably the easiest money in the shop made,” DeBates says. “Once whoever’s balancing learns how to do it, it’s really an easy operation, especially with the new balancers nowadays – the computer does all the work. Profit-wise, it’s probably one of the biggest profit centers in the shop for time invested and what you can charge for it.”

Auto Machine did roughly 120 balance jobs last year, and located in a high rent district near Chicago, the shop charges $430 for the average V8 balance job. A four cylinder is less work, but still pulls in $280.

“I’m on pace right now this year to do a 150 balance jobs,” DeBates says. “That adds up real fast and that’s why I say for what you invest in a balancer with a little bit of word of mouth and a little bit of advertising about it, you can easily pay for that balancer within a year. I can make more on it per hour per unit than just about anything else in the shop.”

Not only is balancing itself full of opportunity, but that same balance work can lead to more engine work being done for that same customer.

“We’ve got people who are really taking the bull by the horns and virtually everything that walks in their door gets a balance,” Neal says. “Now, there’s two reasons for doing that. The first one is they have the opportunity to really inspect the assembly. The second side of it is their net revenue has radically gone up, and there is only one reason to be in business and that’s to make money. We don’t want people to buy a trophy from us, we want them to buy an income producer.”

As an engine builder, every time you touch a crank, you should be thinking about where the rest of that engine is and what additional work you could be doing.

“Now, because you got that crank in your shop, you have the opportunity to talk about block work, head work, peripheral support, assembly work and so on,” Neal says. “Back in the day, sales guys were trying to sell shops crank grinders to get the heart of an engine in your shop, and the rest was up to you. That same story exists today, but that tool is the balancer. A new crank grinder today costs somewhere around $150,000. Balancers today are less than $35,000. The difference though is that when that guy grinds that crank, I doubt if he can do a re-grind for $200, and I’ll be damned if he could do it in an hour. Now, for a $35,000 investment I can do a job in less than an hour and make $375. So which of those two would you choose?”

Life may be all about balance, but a balance machine and the understanding of how to do a quality balance job can tilt the scale in your shop’s favor.